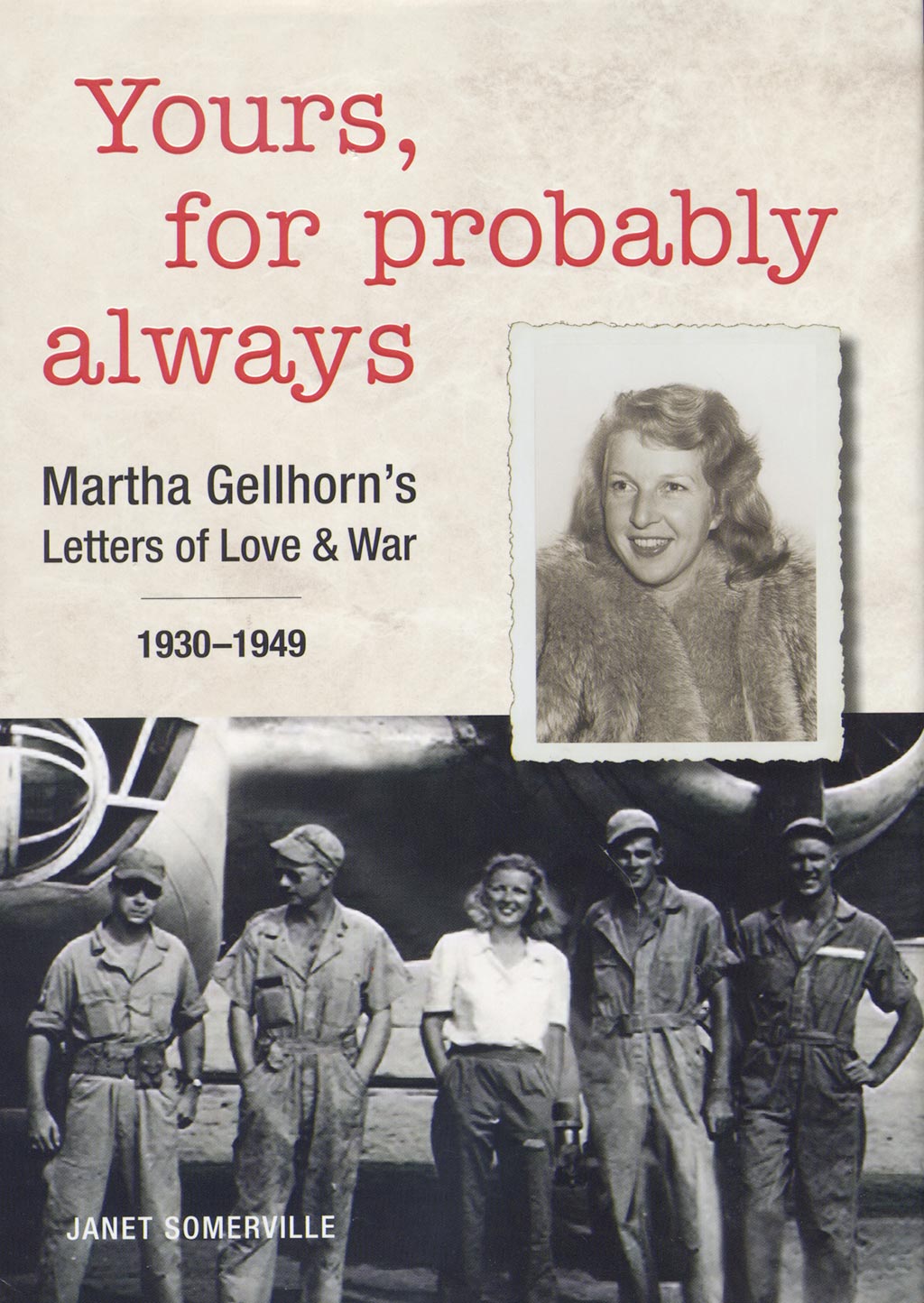

Yours, for probably always: Martha Gellhorn’s Letters of Love & War 1930-1949, by Janet Somerville (Firefly Books, 2019), 528 pages.

This is a curated collection of letters both from Martha Gellhorn and addressed to her from a variety of correspondents, most notably H. G. Wells and Eleanor Roosevelt, interpolated with Janet Somerville’s contextual notes. The overall effect is much like a tragic epistolary novel of grand dimensions. I say tragic because, even as she shares with friends her swooning over Ernest Hemingway, and even as we witness them becoming a couple, we already know this will end badly. And even as we witness her life writ large, schmoozing with presidents and despots, intrepid journalist, model to second wave feminists, first journalist to set foot on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, novelist and restless soul, we know that loneliness and the limitations of age will not be kind to such a person. There is a rape at age 79. There is blindness and disability that prompt her finally to take her life by swallowing a cyanide pill.

The letters are useful to us in a number of ways:

The Mechanics of Power

Martha Gellhorn’s observations on the mechanics of power are prescient. Although they were aimed at the dominant figures of her day, they are, in many ways, transferable to our own time. Gellhorn travelled widely and placed herself deliberately at the forefront of unfolding events. Perhaps this is why she could offer such clear-eyed critiques while others seemed to waffle. I think her experience in the Spanish Civil War had keyed her to Fascism in all its manifestations, so while others looked to England as a defender of freedom and democracy, she saw Chamberlain for what he was long before his appalling meetings with Hitler. In a letter to H. G. Wells dated June 13, 1938, she asks:

Why don’t you shoot Chamberlain, like a good citizen? What a man. With a face like a nutcracker and a soul like a weasel. How long are the English going to put up with these bastards who run the country?

It’s a question we might ask of the English today, the more remarkable for the fact that the person posing it then was 29 years old and addressing an older man whom most of us would find intimidating for his intellect and reputation.

In a letter to Eleanor Roosevelt dated February 5, 1939, she writes:

I see by this morning’s paper … that the Nazi press is calling the President, “Anti-Fascist Number One.” As I can think of no greater term of honour, I am hurrying to write and congratulate him via you. I am also thrilled to see that the Italians are in a fury. In these days, unless the Berlin and Rome press are insulting, you cannot be sure where you stand.

And here we stand, 80 years later, scarcely able to remember how the office of the President of the United States of America was once regarded as the last great bulwark against the spread of Fascism around the globe. Now the office is occupied by a waddling goon who demonizes those who oppose Fascism and, tearing a page from Berlin and Rome, routinely insults those who stand against him.

Later that same year, she again writes to Eleanor Roosevelt:

I do not believe that Fascism can destroy democracy. I think democracy can only destroy itself. It must have so weakened and cheapened and denied itself that it is no longer a moving or inspiring reality: at such a time, this colossal fake that is Fascism can masquerade itself into commanding an historical position.

Despite her confidence in the U.S. as a defender of democracy, and despite her admiration for the Roosevelts, she did not wear rose-tinted glasses. When she heard a rumour that Roosevelt was considering a US $100 million loan to Franco’s government, she was furious. In a letter to H. G. Wells dated October 26, 1940, she asks:

If the US wants to pick up where Chamberlain stopped, appeasing, how is it going to be possible to raise a thrill of honest passion in the hearts of the people, saying: defend democracy boys, but kindly overlook the fact that we are financing a dictatorship which is executing an average of thirty people a day, people who believe in democracy.

Sadly, this has become a pattern of conduct that afflicts U.S. Foreign policy to this day, decisions of expediency (most often to secure resources) at the expense of principle.

In the days of the Spanish Civil War, Gellhorn took it as a given that war would engulf Europe and also that it would require U.S. involvement to provide stability. In July, 1937, writing to Eleanor Roosevelt:

I can’t bear having the Spanish war turned into a Left and Right argument, because it is so much more than that, and increasingly it seems to me the future of Europe is our future, no matter how much we want to be apart, man is one animal and our civilization is not divisible into water-tight compartments.

I wonder how her words might have changed had she been writing today while staring down the ravages of a globally integrated and ideologically justified market economy, an extinction level climate crisis, and a global pandemic. In her own time, it infuriated her that the U.S. was so slow to assume its responsibilities to the rest of the world. Now, as we wait for the U.S. to show some leadership in answering the global crises that threaten us all, we can share something of her fury.

A Feminist Before Her Time

Martha Gellhorn is perhaps the linchpin of second wave feminism by modelling behaviour and documenting frustrations that would become the raw material for the more theoretical writings which would follow. In the late 30’s and early 40’s, Gellhorn commanded a fee of $1,000 per article plus expenses from Collier’s, and during the war, she used one of their accreditations (each news outlet could assign only two accreditations as war correspondents). Most of the time, she presents as the intrepid journalist, one of the boys, out to get the story no matter what, but there are occasions when she lets her guard down. In a letter dated September 22, 1941 to Hortense Flexner, poet and professor at Bryn Mawr, she confesses:

It is … a grave but not important error that I happen to be a woman. I do not think that history will, shall we say, suffer: that mass destinies will be altered and blackened because of this. But, on the other hand, what a waste. I would really have been a very something man, and as a woman I am truly only a nuisance, only a problem, only something that most definitely does not belong anywhere and will never be really satisfied or really used up.

A year later, she complains to Eleanor Roosevelt that the war department won’t let her near the conflict because she is a woman:

… The war dept thinks that woman’s place is in the home, and they do not wish to transport females around to the areas of conflict, nor will they accredit female correspondents to the “armies in the field.” I guess I can still get accredited to furriner’s [foreigner’s] armies all right so that part does not matter too much; but how to get anywhere? It is too late for me to do anything about being a woman, though I would gladly change my sex to be obliging, if it were feasible.

A year after that, in a letter dated June 9, 1943 to H. G. Wells, she reported on the progress of her novel, Liana:

I am very sorry for the girl in the book, but on the whole I am sorry for women. They are not free: there is no way they can make themselves free.

Martha Gellhorn may have thought women are not free, yet she struggled mightily against her own bonds. One of my favourite accounts comes late in the book, with the approach of D-Day. Her soon-to-be-ex-husband, Ernest Hemingway, made a pitch to Collier’s and was given one of their accreditations—his wife’s. Understandably, Gellhorn was furious and, in order to get a story, she had to be creative. She went to Southhampton and boarded a Red Cross ship on the pretext that she was doing a nurse’s story. They let her on board, assuming she’d do a few interviews and leave. Instead, she locked herself in a bathroom until they got underway. As a result, she was the only journalist to set foot on the beaches of Normandy during the Allied invasion. Not even Hemingway did this. He was confined to an amphibian craft. Both Gellhorn and Hemingway filed stories with Collier’s and they were published together in the July issue. No doubt Collier’s was delighted; they got a story from the front lines without having to waste an accreditation on it.

By this time, it was obvious that Gellhorn and Hemingway were finished. It calls to mind something Gellhorn wrote nine years earlier in a letter dated August 6, 1936 to her friend, Allen Grover:

A man is no use to me, unless he can live without me. Odd, isn’t it. Once I’m sure he can live without me, I’m perfectly willing to deliver myself tied hand and foot.

Martha Gellhorn was 27 when she wrote these words and likely lacked the experience to realize she could bind herself to a man who had absolutely no clue what he needed or didn’t need from a woman. While it seemed at first a perfect match—this adventurous woman, endlessly curious, restless, off for months at a time chasing a story—one suspects that Hemingway, for all his bluster, really wanted a woman who would cook and clean and tend to his every infantile need. Towards the end of the marriage, it became apparent Hemingway could not live without her—or at least his version of her—and, perhaps to punish her, pulled childish stunts like stealing her accreditation in an attempt to keep her in her place.

It’s About The Writing

In the end, it was all about the writing. Gellhorn shares with her friend, Hortense Flexner, “five finger exercises” she and Hemingway practise to keep their writing nimble when they have no specific projects to work on. She occasionally shares tales verging on gossip. There is Antoine de Saint Exupéry who stayed one night in Madrid when the hotel was shelled:

She [Hortense Flexner’s colleague] should have seen us taking care of the author of W.S. and S [Wind Sand and Stars] in Madrid, where he spent one day and night and then beat it. He is, so some French aviators I know tell me, a very swell guy, but he is not used to ground artillery and when the hotel was shelled at six one morning, as on many other mornings and was hit five times, he stood in his doorway, an inner room … and handed out grapefruit, in an intense state of nervousness. He had a lot of grapefruit and he evidently thought it was the end so he was sharing his wealth.

Others, like Dos Passos, drew her ire. During a P.E.N. congress in London, he had suggested that in these times of armed conflict, writers should not write. Gellhorn offers a spirited rebuttal to this sentiment in a letter to her editor, Max Perkins, October 17, 1941. It is a valuable statement in that it gives us a clear view of her motivation for writing and it applies with equal force to her journalism and to her fiction:

If a writer has any guts he should write all the time, and the lousier the world the harder a writer should work. For if he can do nothing positive, to make the world more livable or less cruel or stupid, he can at least record truly, and that is something no one else will do, and it is a job that must be done. It is the only revenge that all the bastardized people will ever get that someone writes down clearly what happened to them…

It is important to note that when she writes of “all the bastardized people,” she means all the ordinary people who are treated unjustly in the midst of events beyond their control and who have no recourse.

By the end of the war, I suspect she had concluded that while writing empathetically about those trampled under by the machinations of power is important, on its own, it is largely meaningless if not coupled by a willingness to act. And so she adopted Alessandro, Sandy, an Italian infant orphaned by the war. She saw first hand how thousands of innocents suffered and while she was powerless to solve the problem, she could ease the suffering in one life and perhaps, through that simple gesture, prod others to help. This isn’t exactly the kind of action Hemingway wrote about—adoption doesn’t have the same cachet as getting yourself blown up—but it is precisely the kind of action we need.

Martha Gellhorn’s natural empathy led her, in the creation of fictional characters, to places which would set her afoul of the strict lines that contemporary identity politics have drawn around what one can and cannot write. In her early fiction, she wrote women protagonists. Because she was also journalist, critics surmised that her protagonists were thinly disguised versions of herself and the fiction was thinly disguised reportage. Although she balked at the criticism, it seems to have made her self-conscious about her fiction.

In Liana, her protagonist was a woman, but a woman of colour. Here, she joins Harriet Beecher Stowe and William Styron as a white writer who crosses the race divide. I wonder if perhaps it was her way of refuting her critics. Today, it is almost unthinkable to suppose a novelist wouldn’t draw on their own experience for the content of their work.

Later, with Point of No Return, she wrote a novel with a man as the protagonist. Crossing the gender line was another way of refuting her critics. Gellhorn had been present at the liberation of Dachau and felt compelled to write something more substantial than straight journalism. Even so, the work seems to be haunted by this earlier criticism as she reveals to Eleanor Roosevelt in a letter dated May 16, 1946:

I’ve been panic-stricken about it [Point of No Return] several times, and decided to abandon it, because whereas men apparently have no nerves in writing about women reverse is rare, and I found myself launched on writing about men as if I were one. Suddenly I said to myself, come, come, you might as well admit you aren’t and then the panics set in.

My personal view is that the problem doesn’t lie with the writing but with the criticism which is not a true criticism but a petty snarking that seeks to tear someone down to mask its own insecurities, much as one might steal another’s accreditation because, if they were given their due, they might prove to be an equal or (God forbid) a superior.

In the end, we might confess that the impulse to write is nothing more than a function of the bicameral structure of the brain, much like the impulse to create imaginary friends in childhood, or to yell at God when we are grieving. We do it because we cannot help ourselves.

Someday, and very soon I feel, instead of pursuing a lifelong folly, the passionate desire to find someone to communicate with, I shall simply write. I will at last admit to myself that it is a mug’s game, there is no one to hear and no one to talk back, and the last and good resort is the white page and the faceless strangers who may or may not hear. I will talk to myself on paper; I have been talking to myself, in my brain, silently, all my life.

I first “discovered” Martha Gellhorn’s writing fifteen years ago when I stumbled upon Liana in a used book store. From there, I read Point of No Return, and her Travels with Myself and Another (the “Another” being Ernest Hemingway) and most lately a compendium of her novellas which includes two other books she published, The Trouble I’ve Seen and The Weather in Africa. One of the things that puzzles me is why it took me so long to acquaint myself with such a wonderful writer. I can only surmise that it is because she worked in the shadow of a writer who, in his day, was esteemed the greatest of the modern age. It’s funny how our estimate of a person’s gifts change through time. Today, I regard Hemingway’s work as vastly overrated. Conversely, I want to raise up Gellhorn’s as sadly overlooked. We should celebrate her work, just as she would have celebrated those who were overlooked by the machinations of power. If you share with me that impulse, then Yours, for probably always is essential reading.