Ten years ago to the day, I left the safety of Toronto’s suburbs and rode downtown to poke around the billion dollar militarized zone that former PM Stephen Harper authorized to secure the 2010 G20 summit. Although it was disconcerting to see double concrete barriers and chain link fences snaking around a sizeable swath of the financial district, and although it was disconcerting to note the deployment of an overwhelming police presence (nearly 20,000 officers), and although it was disconcerting to watch technicians installing surveillance equipment at every intersection, and although it was disconcerting to witness “random” stops and searches, nevertheless I captured it all through rose-tinted lenses. I was confident that, because this is Canada, police would observe the rule of law and treat people fairly. The event would be well organized. Everything would be fine.

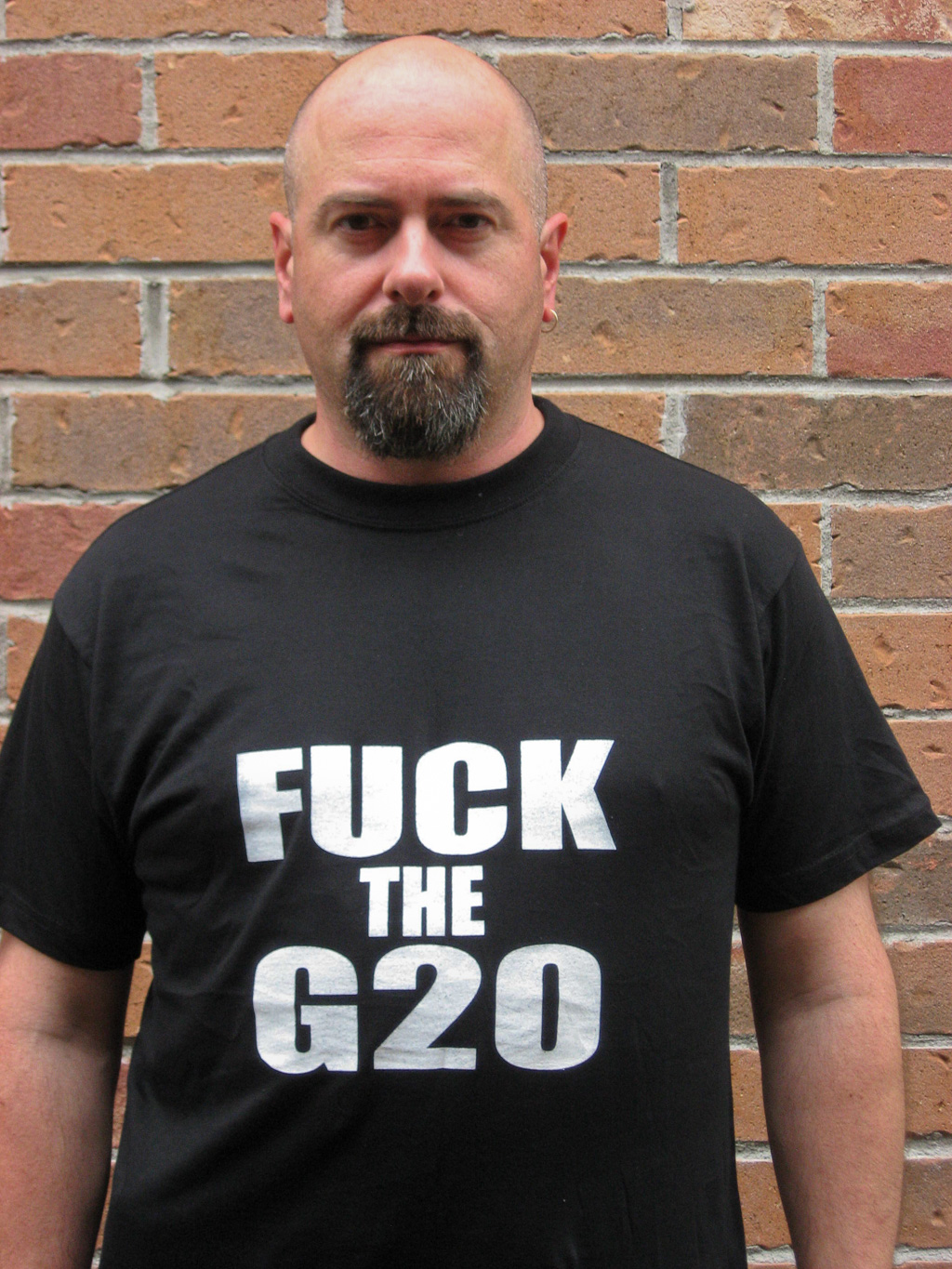

The following day, a rainy June 26th, I persuaded my wife to join me at a protest that would begin at Queen’s Park. On principle, I bought a “Fuck the G20” T-shirt, although the principle I followed is not the principle you’d expect. I was adhering to my personal belief that one should reward cognitive dissonance. How else to describe an entrepreneurial T-shirt vendor at an anti-capitalist rally? We marched down University Avenue, past the U.S. consulate. Tamiko felt uneasy but I pointed out parents with young children and people with balloons and others banging on drums and singing songs.

I can’t remember how it happened—maybe it involved a washroom break—but at Queen Street we were separated from the larger group. We went left when everyone else went right. We passed a line of police in riot gear blocking the way south down York Street. As Tamiko and I stood at the corner of Queen and Bay, all hell broke loose and we were smack in the middle of it. People dressed all in black came running towards us from the west. They passed the line of police in riot gear who blocked the way down York Street. In retrospect, it strikes me as curious that the police held to their position and didn’t chase the wild hoard running past, especially given that the wild hoard running past was smashing everything in its path.

People came up behind us from the east, some from beneath the street, and smashed the window of the Starbucks (now the TD Bank) on the southwest corner of Queen & Bay. Further south on Bay, others had smashed the windows of a police car and set it on fire. I wanted to go down and snap a photo of it, but another contingent of the black bloc mob stood in my way. They swarmed all around us. The hand that held the camera pulled me towards the mob. The other hand had no will of its own. Tamiko held it and she was yanking in the other direction. Seeing the fear in Tamiko’s eyes, I realized I had better go with her. We went into the Eaton Centre. As soon as we got inside, they announced that the Eaton Centre was under lockdown. No one could leave. Someone told us that the subway wasn’t running. Once they lifted the lockdown, we would have to walk up to Bloor to catch a subway from there. To pass the time, we went down to the food court and ordered fries and an internationally branded soft drink.

After about 45 minutes in the food court, a security guard told us we were free to leave by a side door that exited onto Yonge Street. North of Dundas, it was a mess. The black bloc had smashed windows, but not randomly. It appeared the rule was this: if the storefront was connected to a brand that had made an appearance in Naomi Klein’s No Logo, then the window got smashed. They also smashed the windows of the strip club, Zanzibar. At Gould Street, they gave the American Apparel store special treatment, rearranging the mannequins and covering them with shit.

North of Gerrard, people started to scream and run south towards us. It looked as if the black bloc mob had run up to College Street and had done some shit in front of Toronto Police Headquarters. As they ran along College past Yonge Street, they whipped pool balls into the crowd which accounted for the screams and the running. Holy crap! A pool ball in the head could kill a person. It was time for us to get the hell out of there and return to the safety of the suburbs. We ducked through College Park and walked up Bay to Bloor then over to the Bloor/Yonge subway where we caught a train home.

That night we followed everything that was happening, both on TV and on the internet. We watched video of the burning police car played on an endless loop to make it seem as if the whole city was burning. As commentators later pointed out, mobs set more police cars on fire in Montreal the year the Habs lost the Stanley Cup on home ice. But in the midst of it, a reasonable measure of perspective is in short supply. Police started kettling people. That evening, I heard that a friend’s son had been kettled. He was an OCAD student who lived near the action so he had good reason to be where he was. When the police trapped him, they knocked him over and stomped on his stomach. On Canada Day, hundreds of victims of the police marched in protest along with their families and friends. Izaak was there with his boot-shaped bruise and scabbing.

As I reflect on the G20 summit, I find that some of my observations then may have some bearing on events today:

1) The 20,000 additional police were not there to serve and protect.

The additional police were there to serve and protect 20 leaders and their entourages. When a relatively small group of activists turned violent, they took no steps to intervene. They simply held their positions. They were not there as police; they were there as a paramilitary force. They were not there to serve the public interest, their sworn duty. Some lives matter more than others.

2) The police were receiving contradictory directives.

If you think I was suffering from cognitive dissonance when I bought my commodified “Fuck the G20” T shirt, you should have seen all those police officers. On June 25th, when I first poked around the secure enclosure, it was painfully obvious that different forces had received different messaging. As I walked past one of the gates, a police officer invited me inside the secure enclosure, the one the public wasn’t allowed to enter, and asked me to take photos of him and his buddies. Ten minutes later, as I was taking a long shot of the same enclosure, a police officer from a different force yelled at me to stop shooting a secure area and then he carded me. One message that went out to the public was that police were entitled to arrest anyone within five metres of the fence around the security zone if they refused to identify themselves. The police chief, Bill Blair, later admitted that no such rule existed. I guess he was just making shit up. And yet, as I experienced first-hand, some police were happy to treat it as a 500 metre rule. After that, I had no idea how to interact with the police.

3) Police do not appear to understand that, as agents of the state, they are required to observe the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

This became apparent to me as I heard police officers utter the same phrase over and over again: If you’ve got nothing to hide, then you’ve got nothing to fear. No. That’s not how it works. Whether or not a person has something to hide is beside the point. A person has nothing to fear because they live in a constitutional democracy where people are accorded a measure of dignity and respect simply by virtue of the fact that they exist. It’s grounded in a natural rights theory of justice: our rights inhere in us and there is nothing we can do to divest ourselves of them. The slave owning president of the U.S., Thomas Jefferson, described it best when he called those rights inalienable. However, as Jefferson’s own life illustrates, the notion of inalienable rights is a fragile thing. Here, today, we witness yet again how easy it is for police to forget that rights are inalienable. It seems rights are disposable, especially if your skin is brown and you are schizophrenic and difficult to manage.

4) Hard-line policing produces a self-fulfilling prophecy.

After my experience during the G20 summit, I found I could no longer trust police. Me. A middle-aged white guy. If, by their conduct, they lose the respect of someone who looks like me, imagine how much greater the sense of alienation and distrust for Indigenous Peoples and People of Colour. Policing becomes that much more difficult. By policing, I mean real policing. Community building. How can you engage in community building if no one will talk to you? I sure as fuck won’t talk to you.

5) The Toronto G20 summit was a clinic in Naomi Klein’s shock doctrine.

A crisis happens. Or, in the case of the G20 summit, is manufactured. Fear and uncertainty take hold. A right-wing leader throws a shit-load of money at a para-military wall just to see how much of it sticks. In particular, Toronto Police Services grabs its share of that shit-load of money to buy law enforcement toys like sound cannons, armoured vehicles, and all sorts of surveillance tools. PR at the TPS assures the public that it’s all temporary. Once the crisis has passed, those surveillance cameras will come down. Last week, ten years after it went up, I noted that a police box at the intersection Simcoe and Queen Street West was still there. I look around and they’re everywhere. I guess the word, temporary, means something different in police lingo.

6) Hammers and nails.

If you equip a police force with military tools, then all you’ll ever get from it are military solutions. Equip it with mental health professionals, trained negotiators, social workers, youth workers, community builders, crisis counsellors, chaplains. Get the right tools.