This is a piece about the dangers of writing book reviews. But if you want to hop onto that boxcar, you’ll have to ride with me for a while on a different track. My monkey brain can’t leap to book reviewing without first crouching beside a different bunch of bananas. (I apologize, too, for mixing my metaphors.)

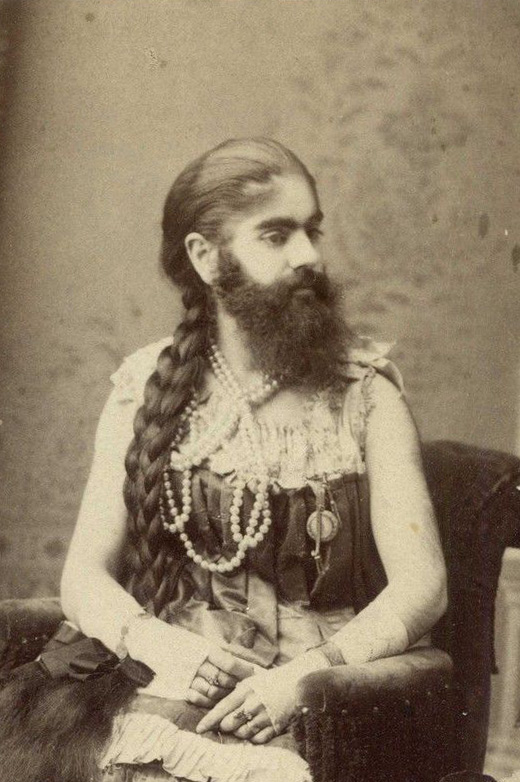

I met the world’s ugliest woman while walking with my camera along a path through environmentally sensitive lands. She was there on a commemorative plaque beside her husband. The plaque said they were the original owners of the land and the woman had donated it to an environmental organization after her husband’s death. The husband was a fierce-looking gent with full beard that reminded me of King Edward VII. As for the wife, she looked like she howled at the moon and licked herself clean each night after a lope through the forest. It would be an understatement to say that she was hirsute.

I took a photo of the plaque and wanted to do a speculative piece, imagining their life together. I wondered if maybe the wife was a man in drag. Maybe they were pioneers of the gay marriage, one dressing up in business suits to pose as a man’s man while the other put on Victorian dresses and presented as a proper lady. But I held off on writing the piece.

Google can be a bitch. The last time I wrote something about somebody long dead, the deceased’s great-great-great-grand-nephew found it and posted a longish comment taking me to task for it. Fortunately, he was good-humoured about the whole thing and could see well enough that I was winking and nodding as I wrote. But what if I wrote a speculative post about this couple and it turned out that they had children? What if some great-granddaughter sprung from the loins of the world’s ugliest woman hunted me down and appeared on my doorstep with a meat cleaver raised above her head?

I did a google search and discovered that the Edwardian husband and his hairy wife did, indeed, have children and so it is entirely possible that, if I wrote a speculative piece about a man/woman prancing in Victorian dress, one of countless indignant descendants would descend upon me and publicly give me proper hell. Although one can’t libel the dead, the possibility that I might be contacted by enraged descendants has caused me to self-censor. I won’t be posting the photo. I won’t be identifying them by name. And I won’t be writing any story about gay marriage pioneers in the old west.

The tendency to self-censor infects book reviewing too. The FTC has a rule that if you review stuff on your blog and the stuff you review has been given to you for free, then you need to say so. According to the FTC, getting an ARC for free from the publisher will somehow bias your opinion. That’s bullshit, of course. What biases your opinion is the fear that you’ll wake up one night with an author pressing the muzzle of a sawed-off shotgun to your temple because he was insulted by your review of his latest limerick collection.

To avoid the shotgun scenario, there is a strong incentive for reviewers to say nothing but nice things. It’s the kindergarten rule of reviewing: if you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all. It isn’t all that helpful to readers, since they have no indication what books to avoid, but it does ensure that reviewers keep all their fingers and other important body parts. When I first started doing book reviews, I made the mistake of writing exactly what I thought of an acutely bad self-published novel (see the next chapter). Sometimes I can’t help myself. And bad writing makes for entertaining reviewing. When the author read my review, he was apoplectic. He emailed photos of lions fucking. He wrote a note suggesting that I deserved to be raped in the same manner as the beasts on the receiving end of these leonine fuckfests. I wasn’t worried. I knew it was an idle threat. He lived on the east coast where they don’t have easy access to lions.

I don’t really care about FTC requirements since I’m a Canadian writing from what I consider to be a Canadian perspective (whatever that is) and am not subject to American laws. But since many of the books I review are from American publishers, I think it’s important to understand what the FTC is on about. I think they lump books together with electronics and cars and household appliances. And yes, if Apple sent me an iPad to review, I would be sorely tempted to gush. But a book? Does a book have enough intrinsic value that it could influence my opinion? What about an eARC—a digital copy of a book that isn’t even in its final form? If I tried to sell it on the open market, what price could I get for it? To be honest, its value is probably less than zero. It’s a liability. Reading it takes valuable time from doing other things. And if it’s putrid writing, then it takes even more valuable time because I have to find inventive ways to clear the toxins from my head.

What the FTC rules don’t capture in my experience is the fact that after I post a book review, the author and/or publisher typically contacts me on the same day to acknowledge the review. More often than not, reviewing is a form of relationship building. That kind of immediacy, through Google and Facebook and Twitter, is unprecedented. And that is a far more powerful influence on the way I present my opinion than any advance copy could be.

For one thing, I don’t offer ratings. That’s a hollow system anyways. As Amazon’s reviewing system demonstrates, the ratings business is easily gamed to improve sales. For another thing, I avoid simplistic evaluations—oh, this is good, that is bad. Instead, I’d rather draw the writing into conversation. What is it saying? How does it say what it is saying? Is it in conversation with other writing? How does it fit within larger narratives? If writing can support this kind of reflection, then the FTC’s (infantile) concern for bias becomes irrelevant.

Afterthought: the genre of book probably also influences the manner of review. Non-fiction is easier to review objectively because I critique the ideas and worry less about ego (both mine and the author’s). But because I review mostly literary fiction and poetry, I usually find the process murkier. My sense is that literary writers invest more of their selves in their words and, as a result, make themselves more vulnerable when they submit those words to the opinion of others.