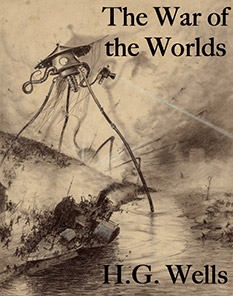

Although The War of the Worlds, by H. G. Wells, concerns an alien invasion by Martians, it is nevertheless relevant in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. Microscopic pathogens figure in the plot. In what a high school English lit teacher might call an example of foreshadowing, the novel opens with:

No one would have believed…that as men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinised and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water.

The Martians undertake an aggressive assault against humanity, or at least against England, and just as it appears they are about to complete their conquest, one by one they drop dead. For all their military might, they fail to anticipate that their exposure to life on Earth might include exposure to pathogens for which they have no immunity.

While a pathogen attacks and kills the Martians, the Martians themselves function like a pathogen in their treatment of humans. Wells devotes most of his novel to the way humans respond to the threat, and it is eerily prescient. There is the conflict between those with direct knowledge of the matter and those who speculate and pass rumours despite their ignorance. Then, of course, there is denial. This takes two forms. There are those who refuse to believe what is reported to them. When the unnamed narrator tries to relate what he was witnessed—the aliens, their machines, their lethal heat-rays—no one will believe him. Maybe he’s trying to perpetrate a hoax. Or maybe he’s exaggerating. They need to see the danger with their own eyes before they will believe the reports of others.

Then there are those who witness the danger with their own eyes yet still engage in denial, either refusing to believe what they have seen, or refusing to believe its implications. One such denialist is the curate who has fallen in with the narrator as they flee the danger. In much of Wells’s writing, he pits reason against the magical thinking that religion engenders. The curate pays the ultimate price for his unreason and, worse, jeopardizes the narrator too. We watch the same thing happen in the context of Covid-19. Evangelical Christian sects defy science-based self-isolation protocols in the belief that their communities enjoy divine protection. Boris Johnson does the same, mingling closely with colleagues, shaking hands and embracing, perhaps grounding his behaviour in the equally magical thinking of ideology. Now he fights for his life in an intensive care ward.

As the Martians progress, the human response devolves into panic, what Wells describes as the “swift liquefaction of the social body.” The fear itself is a form of contagion that brings out the worst in some people. A news seller flees, but not before unloading his newspapers at a shilling apiece, “a grotesque mingling of profit and panic.” And we have this passage which could stand as a parable of greed:

Then my brother’s attention was distracted by a bearded, eagle-faced man lugging a small handbag, which split even as my brother’s eyes rested on it and disgorged a mass of sovereigns that seemed to break up into separate coins as it struck the ground. They rolled hither and thither among the struggling feet of men and horses. The man stopped and looked stupidly at the heap, and the shaft of a cab struck his shoulder and sent him reeling. He gave a shriek and dodged back, and a cartwheel shaved him narrowly.

“Way!” cried the men all about him. “Make way!”

So soon as the cab had passed, he flung himself, with both hands open, upon the heap of coins, and began thrusting handfuls in his pocket. A horse rose close upon him, and in another moment, half rising, he had been borne down under the horse’s hoofs.

We have witnessed similar grasping, some of it personal, like fights over toilet paper, and some of it on the global stage as nationalism rears its ugly head and insists on hoarding resources to the exclusion of others.

But Wells was a progressive and an optimist and concluded his novel with thoughts which, if tweaked just a little, could serve us well in our current crisis:

[O]ur views of the human future must be greatly modified by these events. We have learned now that we cannot regard this planet as being fenced in and a secure abiding place for Man; we can never anticipate the unseen good or evil that may come upon us … It may be that in the larger design of the universe this invasion … is not without its ultimate benefit for men; it has robbed us of that serene confidence in the future which is the most fruitful source of decadence, the gifts to human science it has brought are enormous, and it has done much to promote the conception of the commonweal of mankind.”

Whether we can apply those words to ourselves remains an open question.