The first time I visited Glasgow, it was to visit a friend who had settled in the nearby town of Kirkintilloch. He showed me the sights and I was happy to shoot whatever I saw. However, I sensed a certain — I’m not sure how to describe it — maybe embarrassment? — as my camera sometimes strayed from the more palatable tourist subjects (the Kelvingrove, Buchanan Street, Glasgow Cathedral) to the stuff you’d never see in a brochure (panhandlers outside the Lodging House Mission, graffiti in an alley off Sauchiehall St., empty liquor bottles on a street in Govan). I didn’t mean to embarrass, but with a camera in hand, I felt compelled to shoot what’s there, not what other people wish were there.

My friend’s response brought to mind something we all do: call it pride of place. We tend to tell narratives of the place we call home. Maybe because we need to believe that we have some mastery over our circumstances, that we have chosen where and how we live rather than submitting to forces beyond our control, we tell stories of our place that reassure us we have chosen well.

I have found myself doing the same thing as my friend visits me in Toronto. I show him the sanitized sights (the Eaton Centre, the U. of T. Campus, Yorkville, the ROM, Chinatown, Kensington Market) while pretending not to notice the man on the sidewalk outside the Waverly Hotel with a needle in his arm, or the police shaking down a shoplifter, or the (presumably) schizophrenic woman harassing strangers. Toronto is a wonderful city, I tell myself. Ignoring, for the time being, that I was born here and so never had a choice about living here for the first 18 years of my life, and, ignoring for the time being that, for the rest of my life, I have been too afraid to go anywhere else, I couldn’t have done better for myself. Truly, I am the … uh … master of my universe.

Sometimes, when I’m out with my camera, I play a mental game with myself. It has two steps. The first step is to imagine that I’m entertaining a visitor, like my Scottish friend, and am leading a tour of all the city’s sanitized sights. Through my lens, I tell the narrative of my home; I revel in my pride of place. The second step is to ask myself: how does my narrative produce blind spots? What am I missing when I try to buttress my frail sense of mastery? And then I look again.

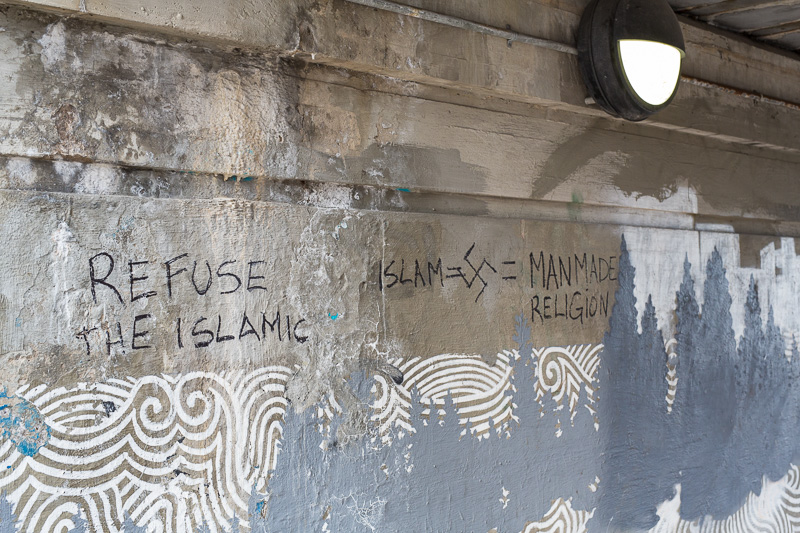

Sometimes what I see offends my sensibilities. I don’t want to believe that some of my neighbours equate Islam with Nazism, or call black people niggers and monkeys and say they belong in prison. I want to tell a story of Toronto the Good. It’s a rosy liberal story of social progress that relegates messages of hate to a less enlightened past. I’d rather not see such things, but they’re there, and I feel it’s important to acknowledge them. If, to preserve the coherence of our narrative, we ignore such messages or, worse, answer them with angry reprisals, we allow them to fester and to reemerge, maybe more virulently.

I’m reminded of recent political developments, both locally and abroad. It was surprising to many middle-of-the-road Toronto voters that, even with an addiction to crack cocaine, shady connections, racist diatribes, bullying, etc., Rob Ford nevertheless maintained a significant base of supporters — his “Ford Nation.” These are people who cannot be swayed by Ford’s personal failings to abandon their alignment with his politics of the hard right. Within the “Ford Nation” is a core that Chris Hedges would identify as proto-fascists, people whose absolute allegiance leads them to engage in brown-shirt tactics. We are witnessing the rise of a similar political phenomenon in the demagoguery of Donald Trump, whose campaign for the leadership of the Republican Party offers virtually no substance but appeals to sentiments shared by a broad swath of American citizens: anti-immigrant, pro-white, anti-Islam, pro-Christian, anti-government, pro-gun, and so on. One doesn’t have to agree with either man’s message, but it would be imprudent to ignore their broad appeal. If we failed to acknowledge them, or, worse, struck back in anger, we’d find ourselves sorely surprised in the electoral process.

When I stare at a message that undermines my personal narrative of place, I find it almost impossible to see clearly. I’m tempted to point my camera in another direction. But what I need to do is to point my camera directly at the message, and then to look through it. In my view, the message itself is rarely the message; the message is merely the trace of a deeper narrative. I can’t read the narrative in its details, but most likely it is a story of powerlessness and fear.

It’s paradoxical that if I want to tell a narrative that reflects a mastery over my own circumstances and my place in the world, the best way to do that is to offer my neighbours a measure of mastery over their own circumstances and their place in the world. I can’t do anything grandiose, like implement public policies that guarantee widespread inclusion, but I can do simple things that are nevertheless meaningful. I can see people. I can acknowledge their value. I can listen to their stories.