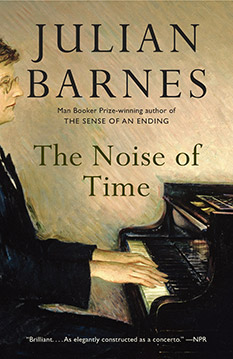

In this fictional account of a historical figure, Julian Barnes imagines how Shostakovich survived in Stalinist Russia. Barnes makes much of irony as a survival strategy, an ontological stance, a means of shielding one’s self from the solar glare of true belief. I draw a parallel with Pico Iyer’s “Toronto” essay in The Global Soul where he discusses the Toronto habit of irony to which outsiders are often tone deaf. It is the mode of communication whereby two people who share the “irony decryption key” can share with one another while others within earshot have no idea they don’t mean what they say. In Toronto, we engage in irony as a defence against the overbearing cultural dominance of our American neighbours. While our situation is not so dire, I think the comparison to Shostokovich’s position in relation Russia’s cultural demands still holds.

The novel also offers opportunities to reflect on synaesthetic experience—the collision of competing sense. There is a recurring reference to the opera, Lady MacBeth of Minsk. I tend to think of opera as inherently synaesthetic, but here, the synaesthetic experience has more to do with the collision of music (as a pure auditory experience) and ideology (as a visual experience in the same way all words are visual and signify ideas [circumventing the ears]). See my thoughts on Marshall McLuhan’s The Gutenberg Galaxy in this regard.

Towards the end of the novel, there is expressed (by whom? Shostakovich? the narrator? Barnes?) the hope that the music might outlive or at least transcend the ideological context from which it arose so that it might be experienced as unfreighted music. Is such a thing possible? In the same vein is the old musicological joke (not so funny, really) which I heard from my first piano teacher probably before I counted years in double digits. Musicologists are the butt of the joke: they’d rather write about music than make it. But, in keeping with synaesthetic experience, maybe musicology is a both/and proposition. Maybe there is no such thing as a pure and transcendent music. Maybe all music demands words, the way a balloon demands ballast, to keep it from floating away into irrelevance.

I sense an overlap of the ironic and the synaesthetic experience. Both facilitate communication on multiple channels simultaneously. That also speaks to the form of Barnes’ novel which eschews the traditional linear narrative with its unfolding time-bound drama in favour of choppy bits which coalesce in the reader’s brain to produce a simultaneity of experience.