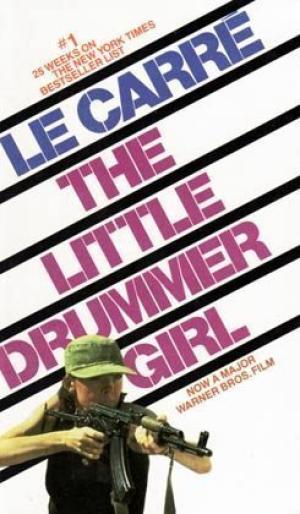

A Le Carré spy novel is more than just another cheap paperback thriller. That is what we learn from the dust jacket of The Little Drummer Girl. According to the L.A. Times: “Le Carré’s ability to create character, dialogue and event approaches the amazing … THE LITTLE DRUMMER GIRL confirms without qualification his status as a writer of elegance and importance.” And the San Francisco Chronicle tells us that Le Carré “[a]dvances the spy novel into the ranks of literature through an examination of moral questions down to their clouded depths.”

In my gullible youth, I was easily deceived by dust jacket puffs. Once, I tried to wade through Robert Ludlum’s The Bourne Identity on the promise of an engaging read that would be both stunning and exhilirating. Instead, I found it tiresome and stupid. The only respite from this cure for insomnia came from an unwitting belly laugh introduced when the main character teams up with a Canadian spy. (Is it only Canadians who find the notion of a Canadian intelligence community so amusing? and improbable?) Almost the first words uttered by this woman, the spy from Canada, is Canada’s Latin motto: a mari usque ad mare (from sea to sea). One can’t help but suspect that Ludlum’s only research was to look up “Canada” in the Encyclopaedia Brittanica. Even if he had only gone to the corner convenience store and button-holed one or two Canadian tourists, he would quickly have discovered that most Canadians have, at best, a flamboyant apathy, and at worst, an outright contempt, for most customary badges of patriotism—anything that smacks of American-style patriotic fervour.

Thankfully, Le Carré is a better writer (and a better researcher). But a writer of elegance and importance? A literary figure? Let’s examine the evidence.

First, consider point of view. In the opening chapter, Le Carré gazes in so many directions, he gives the reader a stiff neck. The story begins with the account of a terrorist bombing at an embassy in Germany. A German agent is assigned to investigate, and we anticipate that this character, Alexis, is, if not the protagonist, at least someone of consequence to the story. Instead, he proves to be not merely minor, but utterly trivial. But we can forgive Le Carré a misdirection here or there, can’t we? This is, after all, a spy thriller, and what is a spy thriller without some misdirection—even if the victim happens to be the reader.

More unsettling is a survey of witnesses to the bombing. Le Carré treats the reader to a tour of more brains than even god could manage in the space of a paragraph. “A melancholy Scandinavian Counsellor, for example, was still in bed, suffering from a hangover brought on by marital stress. A South American chargé, clad in a hairnet and Chinese silk dressing gown, the prize of a tour in Peking, was leaning out of the window giving shopping instructions to his Filipino chauffeur. The Italian Counsellor was shaving but naked. He liked to shave after his bath but before his daily exercises. His wife, fully clothed, was already downstairs remonstrating with an unrepentant daughter for returning home late the night before, a dialogue they enjoyed most mornings of the week. An envoy from the Ivory Coast was speaking on the international telephone, advising his masters of his latest efforts to wring development aid out of an increasingly reluctant German exchequer. When the line went dead, they thought he had hung up on them, and sent him an acid telegram enquiring whether he wished to resign. The Israeli Labour Attaché had left more than an hour ago. He was not at ease in Bonn and as best he could he liked to work Jerusalem hours.” The chief sin of this passage is not a wandering point of view, but rather an appalling disregard for relevance. The entire passage could have been excised without detracting from the novel.

The sure sign that an author has lost control of point of view is a proliferation of adverbs. Adverbs are impossible without the (at least implicit) presence of an intrusive authorial voice. Thus: “The Labour Attaché watched her down the path—a nice style of walking, sexy but not deliberately provocative. He closed and chained the door conscientiously, then took the suitcase to Elke’s room, which was on the ground floor, and laid it on the foot of her bed, thinking loyally that by leaving it flat he was being kinder on the clothes and records. He put the key on top of it. From the garden, where she was implacably breaking hard ground with a hoe, his wife had heard nothing, and when she came indoors to rejoin the two men, her husband forgot to tell her.” (Underlining mine.) One cannot know that a thing is done “deliberately” or “conscientiously” or “loyally” or “implacably” unless one has access to a character’s consciousness which only a god’s omniscience can afford. If an author intends an omnicient voice, then adverbs are acceptable, but Le Carré writes in the latter half of the 20th century, not the 18th century. More appalling is his use of the adverbs “actually” and “clearly.” (Once is too frequent in any novel.) Not only do these adverbs commit the author to a wide—ranging point of view, they betray the author’s willingness to compromise his integrity (as a wordsmith) by using words which signify nothing.

While adverbs may be justified on occasion, the simile is rarely defensible. Not only does it unmask an uncontrolled authorial voice, it reveals a voice in need of wit. And Le Carré is acutely witless in his indiscriminate application of the simile.

• “He could be heavy, and he could be so light you’d think they’d lost the soundtrack.”

• ” … in less that forty minutes they saw Yanuka pull against his chains … like a chrysalis trying to burst its skin … “

• “A cracked voice, like someone dropped him when he was a kid.”

• ” … where the drumming of the London-bound trains as she lay in bed made her feel like a castaway taunted by the glimpse of distant ships.”

And so on … simile upon simile, cascading over the brain, like a … like a wordy waterfall.

I don’t wish to be understood as condemning this particular literary device. However, its appearance as an effective tool is rare. One famous (or infamous) use of the simile appears in Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage, and it is memorable precisely because it stands in stark relief to the rest of the text: “The red sun was pasted in the sky like a wafer.” This is not to every critic’s taste. But the reason the debate about Crane’s simile persists (and therefore is successful) is that it is more than a simile; it is also religious imagery and landscape painting. In only ten words, Crane signifies more than most authors in the course of an entire book.

It would be disingenuous to shred Le Carré without offering an example of good writing for comparison. Here are a couple of my favourites—two works which, in some respects, are opposites. There is Hemmingway’s The Sun Also Rises, spare, with scarcely a trace of the author. Then there is Lowry’s Under The Volcano, rich, dense prose, with the pressing sense that at any minute, the main character, the consul, might break down and confess that, yes, he is indeed the author. Yet both novels have this in common—there is not a word to spare. If even a single word were misplaced, these books would be diminished.

I can’t say the same for Le Carré.