Writing in the mid-1930’s, Henry Miller reflects on the urge to piss. While he acknowledges the satisfaction he gets from emptying his bladder, he also confesses a feeling of anxiety around the question of where that emptying will happen:

I am a man who pisses largely and frequently, which they say is a sign of great mental activity. However it be, I know that I am in distress when I walk the streets of New York. Wondering constantly where the next stop will be and if I can hold out that long. And while in winter, when you are broke and hungry, it is fine to stop off for a few minutes in a warm underground comfort station, when spring comes it is quite a different matter. One likes to piss in sunlight, among human beings who watch and smile down at you. And while the female squatting down to empty her bladder in a china bowl may not be a sight to relish, no man with any feeling can deny that the sight of the male standing behind a tin strip and looking out on the throng with that contented, easy, vacant smile, that long, reminiscent, pleasurable look in his eye, is a good thing. To relieve a full bladder is one of the great human joys.

Henry Miller, Black Rain

Another time and another place, and yet Miller’s words could easily (ahem) pass for my own. It’s as if he’s giving expression to an eternal truth.

I don’t have an expert grasp of urinary tract mechanics, but I do know that as you get older, your bladder loses its capacity. For men, it has something to do with the gradual enlargement of the prostate gland. Imagine you have a shoebox that holds a ball and a balloon and you’re asked to fill the balloon with water. All the young men get shoeboxes with tight little marbles, so there’s lots of room for the balloon to expand. Meanwhile all the older men have to swap out their youthful marbles for big spongy softballs that take up more space in the shoebox.

As someone who likes to take long walks through the city’s streets, my shrinking fluid storage container has become an issue. I’m grateful for the fact that I live in a city whose chief geographic feature is a network of ravines. I can often amble down a path and find a concealed spot behind a bush or a tree, enjoying the additional cover that Summer’s foliage gives me. Winter is more problematic for two reasons. First, there is less natural cover because all the leaves have fallen. Second, on particularly cold days, exposure can present certain hazards to more tender parts of my skin. I am also mindful of the fact that the natural solution is not particularly appealing to a lot of women and is out of the question for people with certain physical challenges. Besides, there are many locales in the city where the natural solution isn’t an option in any event.

One of the problems in downtown Toronto is that, despite the lack of natural options, it offers few public washroom alternatives. There are the public libraries and facilities like rinks operated by Toronto Parks and Rec. Most public washrooms aren’t public at all but are associated with POPS (privately owned public spaces) like the washroom upstairs in Maple Leaf Gardens or in shopping spaces along the PATH. One can find decent facilities in the basements of most buildings on the U. of T. campus. Failing these, there’s always recourse to Starbucks or Tim Hortons. I used to feel compelled to buy a coffee to justify my use of these facilities, but this has become counterproductive since I have to pee again almost the instant I’ve finished my coffee.

In beforetimes, I still had enough options that I could go for extended walks without sharing Henry Miller’s anxiety about where to relieve myself. I was always confident I’d find something. But the pandemic put a crimp in my usual walking habit. Things came to a head on the morning of June 1st. I had started the day with a breakfast that included an orange juice, cup of coffee, and a glass of water. Although my wife was working from home, this was one of those days when she had to go in to the office and, because she had to bring a laptop with her, I offered to carry it down for her. My plan was to go on from there with my camera, making an extended photo walk of my morning. All I had to do was use the bathroom in the basement of the building where my wife works and then I would be on my way. It’s one of those bathrooms on the PATH and so people tend to regard it as a public washroom even though it’s on private property.

I went downstairs and damn but they’d locked it. There was a notice on the door stating that, because the province was in the middle of a 3rd wave, the owner of the building had closed the bathrooms as a precautionary measure. I had no choice but to start walking. At Front & York, I had an early bladder twinge and realized there was no way I was going to make it through my intended route without relieving myself somewhere along the way. I thought maybe I could find an alley and duck behind a garbage bin. But the further I walked, the more pressing my need, and nowhere did I see a location that would give me enough cover. It wasn’t until Spadina, in an alley just south of Richmond, that a solution presented itself. There was a portable toilet just in from the sidewalk. I tried the door and it opened, so I stepped inside and eased the pressure on my bladder. Yes, it smelled, and no, I didn’t touch anything that wasn’t attached to my own body, but it fulfilled its function and I left a happy man.

Stepping away from the cubicle, I saw that it served a small construction site. A man stood on the sidewalk eating a fruit cup for breakfast and I realized he was probably the foreman. He smiled at me and asked how my day was going. I smiled at him and hiked up my pants and said it was going well thank you; and how’s it going for you? He said his day was going well, too. We nodded at each other and I walked away, self-conscious, like a criminal caught in the act. A week later, the Toronto Public Library tweeted that it would once again be making its washrooms available to the public. Thus ended a long stretch during the Spring when it was impossible for Toronto residents to find a lawful means to relieve themselves in public spaces.

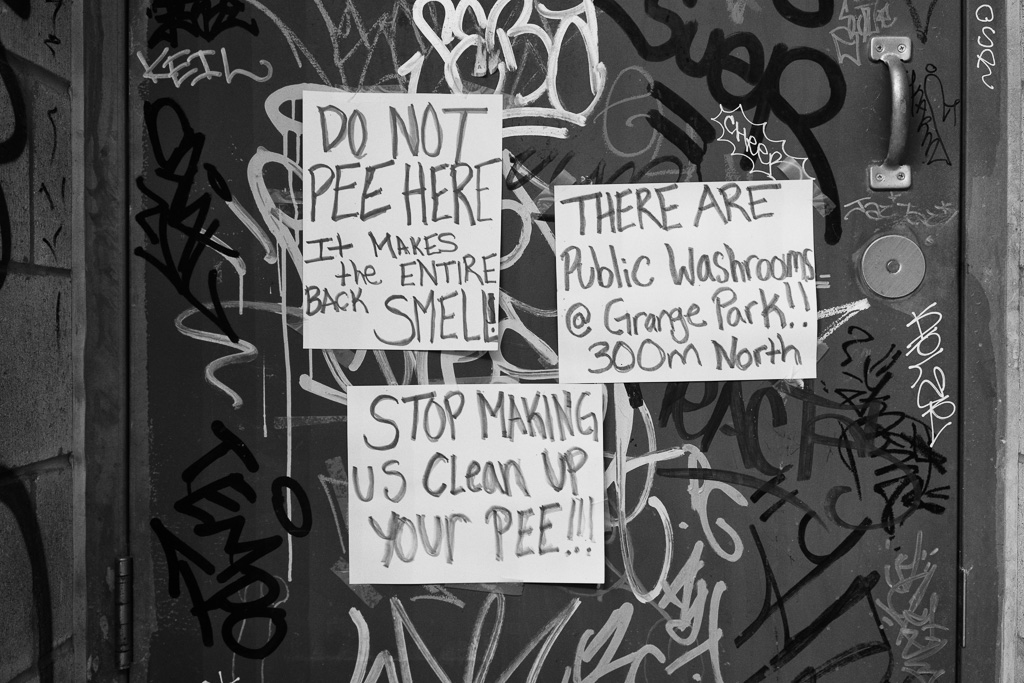

In Toronto, the challenge of finding relief for one’s bladder is not peculiar to these times. A long history of Nimbyism has roused local citizens to an almost religious fervour in their denunciation of the public lavatory. One can’t help but sense a certain class association leaking through the narrative. There is nothing inherently wrong with the idea of a public lavatory (especially in this age of modern plumbing and sophisticated sewage treatment), but there is definitely something wrong with the patrons of these facilities. Toronto’s hostility to the public lavatory matches the hostility it brings to other design decisions, like benches deliberately built to be uncomfortable so that people don’t spend too much time on them.

What is peculiar to these times is the way the pandemic has provided cover for long-standing hostilities. It’s easy enough for critics to expose hostile design as a move against marginal populations; it’s a trickier beast when the city makes those moves in the name of public health. We look at the recent sweeps of homeless populations and listen to the mayor argue on the basis of public sanitation that it’s safer for the homeless to live in city-run shelters. Nevertheless it’s hard to take seriously claims that the city is motivated by safety concerns when, even as the mayor speaks, police are cracking skulls in the background. As the police cart away the homeless and their advocates, the trucks arrive to cart away the portable toilets too. The two travel hand in hand.

In Toronto, there is a strong association between poverty and having to go to the bathroom. Wafting over it all is the stench of shame. I even get a sense of that shame when I’m out on a photo walk and note a pressing need. However, shame is not a given. As Henry Miller makes clear, urination can be cause for great joy. The shame is something we’ve chosen to nurture. It festers in our streets. It runs between the cracks of our sidewalks. Yet in my estimation what truly makes it shameful is that the urge to pee speaks to a common need that could be answered with a social good, whereas we have chosen to treat it as a private problem that deserves our public hostility.