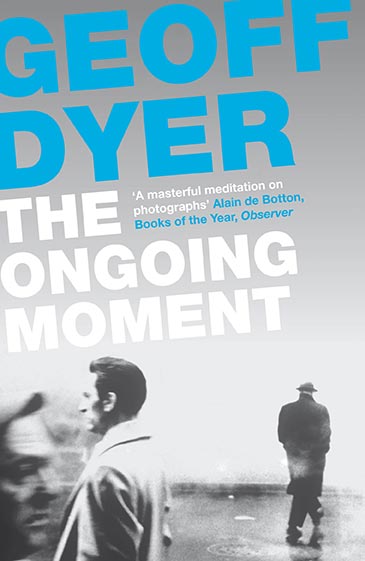

Geoff Dyer’s The Ongoing Moment is a continuous cover-to-cover meditation upon the art of photography. I say “continuous cover-to-cover” because the book has no breaks, no arbitrary chapter divisions. Instead, it’s a series of riffs that follow one another in an associative way. He writes about Stieglitz and his relationship with his wife, Georgia O’Keefe (and with other women, too). He writes about hats and accordions. He wonders why so many pioneering photographers took photos of blind people. Despite the meandering path, he names what he writes about, or at least points the way, by prefacing each new riff with an epigraph. Nevertheless, there’s one concern that goes unmentioned. It’s there. But Dyer never draws it into full view. It lurks in the interstices of the text. He hints at it when he describes his approach as aleatory. Remember that Dyer has previously written about jazz, and so it’s not far-fetched to suppose that he would grab a term from the world of jazz to describe the way he writes about photography. His approach to describing his approach is synaesthetic. He mixes up the senses.

I don’t think the synaesthetic approach to describing photography is peculiar to Dyer. I think it’s natural to talk about one medium by drawing analogies to another. In Dyer, this reaches a fortissimo near the end of the book when he describes a photograph by Walker Evans titled Main Street, Saratoga Springs. The photo is in the MoMA collection and you can view it here. After describing the photo and noting how the rain-slicked street looks more like a canal than a street, Dyer goes on:

Main Street, Saratoga Springs is a quietly audible photograph, preserving not just the view of the street but its sounds: the swish of an occasional car, the slow drip of rain from trees. What you hear most clearly, though, is a sound from earlier in the day: the bell — the memory of the bell — as you entered the barber shop, alerting him to your arrival. He was tipped back in the customers’ chair, comfy as a sheriff, reading a paper that he began folding away, taking in the unfamiliar face (in need of a shave) at the door, glad of the custom, confident in the knowledge that if it was a haircut you wanted you had come to the right place …

There’s a sense in which every photograph gives expression to a wider yearning. There is, beyond the photograph, a fuller experience: a taste of grit in the air, dust in the nostrils, traffic rumbling on the street, leaves in the wind, rain crashing like applause. The photograph reduces the full experience to a single sense. And yet, sometimes, the images can channel a path back to the other senses. It evokes something. We taste the grit. We hear the traffic. Even as the subject lies still in the image, all our senses come alive.