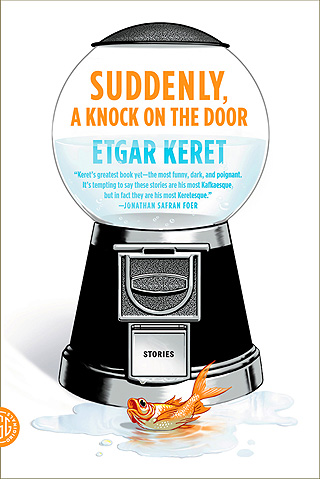

Etgar Keret has a new collection of short stories out and it’s called Suddenly, A Knock At The Door. They are great stories. You can read all about them on other web sites. You can learn about how they combine the ordinary and the bizarre in the same sentence. You can read about how short they are, how economical his approach. How he’s young(ish)—the voice of a new generation of Israelis. How he avoids direct political engagement and doesn’t use his stories to ground a clear ideological message. Other reviewers have already said all those things and there’s no sense in me repeating them, especially when they’ve said these things so well. In fact, I can’t think of anything fresh to say about Etgar Keret’s latest collection. I do have a question, though. When I look at the UK edition of the book, it looks straight-forward enough. But when I look at the North American edition, I can’t help but wonder… The North American edition shows a goldfish in a puddle. That’s easy enough to explain. It comes from one of his stories, What, of this Goldfish, Would You Wish? It’s about an aspiring documentary filmmaker who knocks on doors and asks people: “If you found a talking goldfish that granted you three wishes, what would you wish for?” It all goes well until he knocks on the door of a Russian immigrant named Sergei Goralick who just happens to own a talking goldfish that grants wishes. The North American edition also shows a bubblegum machine. That’s easy enough to explain, too. It comes from another of his stories, Lieland, in which a young man’s lies assume a life of their own and start mingling with other people’s lies. He has a dream in which his dead mother demands that he buy her a gumball. Hence the gumball machine on the cover of the book.

Here is my question: why does the gumball machine on the North American edition look like its wearing a kippah? Is it a Jewish gumball machine? Does it dispense kosher gumballs? Why?

In an interview with the Guardian, Keret describes himself as more a Jewish writer than an Israeli writer. Maybe the cover artist sensed that.

Regardless of his self-assessment, I think Keret is a highly political writer. But instead of writing stories about the external world he inhabits, the world of competing forces and money and people struggling over beliefs, he writes stories about the interior world we inhabit. It’s an absurd and contradictory world, made moreso by the absurd and contradictory world we have built for ourselves out there where it’s real. Politics leaks into our dreams and twists them into goo.

By way of illustration, consider Keret’s longest story, Surprise Party. We can read it in a straight-forward (literal) way, as the story of a woman named Pnina who throws a surprise party for her successful husband, Avner Katzman. Only three people show up: a bank manager, an insurance agent, and Avner’s dentist. They talk to Pnina for a while, but it’s clear Avner isn’t going to show. Avner calls, but hangs up before Pnina gets a chance to speak to him. It seems things haven’t been going well for Avner which is why Pnina threw the party in the first place. The three guests join Pnina on a car ride to Avner’s office to make sure he’s okay. On the way, the insurance agent muses: “The truth is that he’s not worried about Avner killing himself, because his life insurance policy doesn’t cover suicide.” When they get to the office building, Avner has already left. The security guard tells them that Avner asked for help cocking his gun. Two of the men go home, leaving Pnina alone in a car with the bank manager. He makes a move on her and she slaps him in the face. The last time she slapped somebody in the face, it was Avner, and he was being as much of a dick then as the bank manager is now. The story ends on an indeterminate note with the insurance agent wondering to himself if things worked out for Avner. We have no idea.

After a first reading, the story seems unsatisfactory. But what if we read it differently? What if we read Pnina as Israel? She’s supported by shallow self-interested pricks. That could quite aptly describe Israel’s relationship with the UK, the US, and Canada. Canada could be the morbid insurance agent with the Band-Aid on his nose. I’m not suggesting that Keret would endorse such an interpretation. But it’s worth considering. I mean, why the hell not? We can think of it like this: the infected world of politics leaches into our consciousness and infects the world of our ordinary thoughts and the ordinary stories those thoughts would otherwise tell.

Below are links to Keretphernalia:

Writers & Company (CBC) – Eleanor Wachtel’s interview