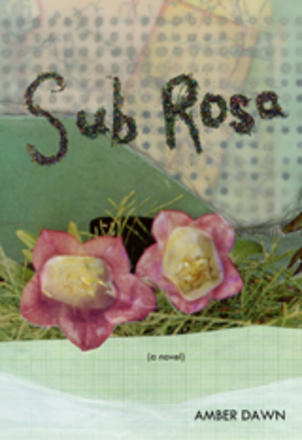

I don’t know what to make of the novel, Sub Rosa, by Amber Dawn. I suspect my difficulty with this novel has as much to do with my personal expectations as with the novel itself. Those expectations come from a couple sources. First, there’s the author profile on the Arsenal Pulp Press web site which lists such accomplishments as the production of an “award-winning, genderfuck docu-porn, ”Girl on Girl,”” and “director of programming for the Vancouver Queer Film Festival”. Even more pointed is her self-description in a shameless interview: “For clarity’s sake, when I say “myself” I mean a queer, kinky, femme, survivor, Canadian small-town born, poor, sex-worker, feminist with a strong passion for experimental artwork and transgressive identity-based art making.” With those two profiles in mind when I bought the book, I was expecting something a little more experimental, a little more transgressive. However, the book I read didn’t feel like a book written by a genderfuck docu-porn producer. It felt more like a book written by an MFA grad. Oh wait. The Arsenal Pulp profile mentions that Amber Dawn has an MFA in Creative Writing from UBC.

To be fair, Sub Rosa uses a wonderful conceit: it’s like Harry Potter for sex trade workers. Sub Rosa is the sex trade’s answer to Diagon Alley. It’s a magical place hidden from the rest of the city where a select group of pimps take their workers (Glories) to live as happy families while working the “live ones” who arrive each night like horny muggles. Little is a runaway teen “rescued” by a pimp named Arsen. She can enjoy the safety and perks of living in Sub Rosa with Arsen’s family of girls on condition that she work the Darkness until she earns her dowry. There, she is raped and beaten like all the other girls before her. But once she has $500 in hand, she takes her place in her new home and all the pain and suffering magically disappears. As Little settles into her new life, a pall comes over the secret community—a police car has parked at the entrance of their alley and they have to stage a “blackout” to protect their secret status. Driven to enhance her own position in the community, Little returns to the Darkness and, thanks to her magical abilities, restores Sub Rosa to its former life. In effect, Amber Dawn’s Sub Rosa is a happy-go-lucky, tongue-in-cheek paean to the countless girls who become invisible when they fall into the sex trade.

But why that tone? My immediate response is to assume that a transgressive conceit has been undone by a conventional execution. I had been expecting the language to be wild and unruly. Instead, what I read was controlled and measured.

The day I bought Sub Rosa, I was also sifting through the shelves of a used bookstore in Dundas, Ontario and stumbled on a volume of poetry, Echoes From Dusty Rivers, by Dannabang Kuwabong. As with Sub Rosa, I was drawn to Echoes because of the expectations it raised. As with Amber Dawn, the photo of Dannabang Kuwabong creates an impression. The bio tells me that Mr. Kuwabong was born in Ghana. A conventional person like myself, the victim of a liberal arts education, is always on the prowl for alternative voices and fresh expressions. “Ah,” I said to myself as I looked at Mr. Kuwabong’s traditional garb, “some authentic Ghanaian poetry.” (The only Ghanians I know wear suits.) Then I read more closely. The blurbs on the dust jacket were from a professor at McMaster University and a Hamilton resident. In other words, as I stood in a bookstore on the outskirts of Hamilton, I was holding the work of a local poet. What’s more, it was a generic work; reading further, I discovered that Mr. Kuwabong was an honourary fellow of the Iowa International Writing Program. I don’t doubt that the poetry is suffused with the poet’s formative experiences in Ghana. But I do doubt that the poetry is executed in a style that has anything to do with the culture of Ghana, whatever that might mean.

I wonder if Sub Rosa doesn’t succumb to a similar difficulty. It offers a good idea—a conceit as I called it. But the style of its execution is at odds with the world it reveals.

There is, of course, another possibility. Maybe Amber Dawn is using the clean middle-class MFA style to play up the kind of collective dissociative disorder that is necessary to maintain the illusion of pristine cities free of social challenges. Many of today’s modern cities (Toronto, for example) depend on magical thinking that treats great swaths of its streets with a cloak of invisibility. A bright, airy prose seems almost to satirize the point-of-view assumed by many municipal politicians. For the time being, I’m not prepared to say whether this is a deliberate strategy on the part of Amber Dawn. Let’s wait and see what else she writes.