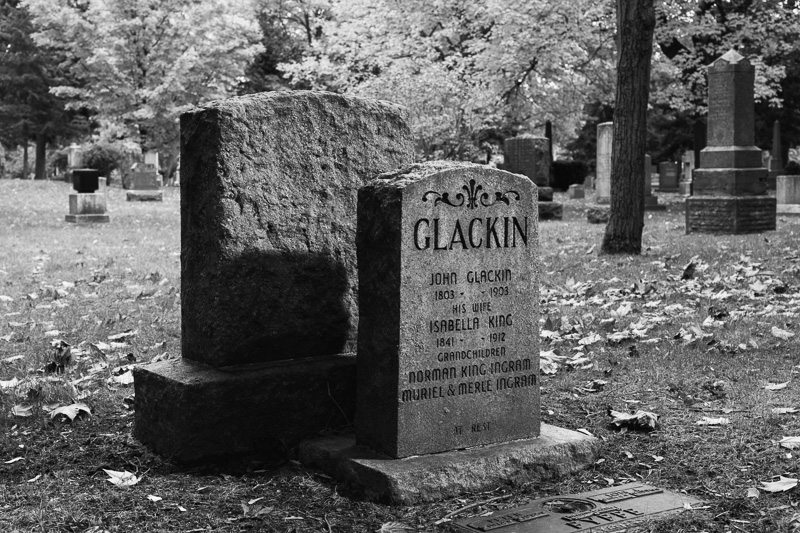

I went to St. James Cemetery with a view to capturing the site in the throes of its annual “Changing-of-the-Colours” ritual (otherwise known as autumn). However, when I returned home and examined my shots of headstones with their backdrop of yellows and oranges, then experimented a bit, I decided they all look better as black and white images, which strikes me as an odd thing to conclude when my intention had been to capture colours.

As I walked through the cemetery, I found myself entering a Zen state. First was the enveloping silence. As I pressed further into the grounds, the sounds of the city—traffic, construction, shouts—receded and other gentler sounds drew to the foreground, the chatter of leaves whenever the wind picked up, the sound of my own breath in its regular rhythm, and—of course—the “sound” of my ceaseless interior monologue.

Second was the rising awareness of death all around me, the death of my progenitors, the prospect of my own death, and—with our newfound admission of our planet’s limits—the end of all life. I don’t treat death as a foe to be beaten back but, in the spirit of Buddhist philosophy, I welcome death as an old friend and invite death to sit with me in my thoughts.

In a way, photography is an optimistic gesture because it implies a faith in the presence of viewers who will follow me. My children at least. Maybe even grandchildren. A wider viewership if I’m lucky. The same holds for this journal [my first iteration of this post happened in my personal journal] which is not written solely with a view to working things out in the privacy of my own thoughts, but with a consciousness that it might be taken up by others after I die. If I were to use this solely to work things out, then I should have started burning my earlier volumes by now. Still, my optimism can extend only unto the middle ground. Inevitably, my (digital) photography will become uninterpretable as the softwares that can read it are deprecated. And the language in which I write my thoughts will become obscure (as is true now of ancient Greek) or it will vanish altogether.

I photograph a toppled monument—the death of memory—which is a second kind of death. As with my photographs or my journaling, a monument is an optimistic gesture because it implies a faith in the presence of descendants. They will come and leave flowers. Even strangers will note the names and read the epitaphs. But weather and lichen eat away at the words, and the stones on which the words are engraved fall over and crack. In time, those they mark lie forgotten.