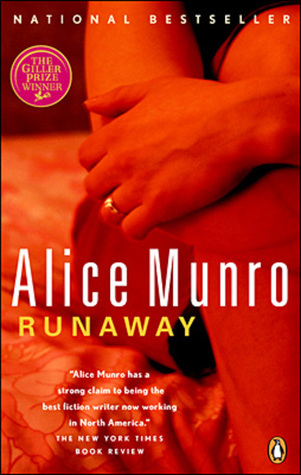

So there I was, two weeks ago, lounging by the side of a pool in Punta Cana, reading Runaway, Alice Munro’s latest collection of short stories, when a woman in a bikini stopped at the foot of my chair and said: “I’ve started reading that, too. Just finished the first story. So what’s with the goat? Did the husband really kill the goat?” Ahhh … what a sad moment in my life! To learn that the only way I can attract the attention of a woman wearing a bikini is to sit by the side of a pool while reading a book by Alice Munro. Afterward, my sister-in-law—who had overheard our conversation from a distance—wondered what I had said to the woman. Because my sister-in-law sometimes teases me about my vocabulary, I said: “I told the woman I thought Munro’s treatment of the goat was a postmodern commentary on Eliot’s objective correlative.”

It’s amazing how a few well-chosen words can kill a conversation.

So what’s with the goat? My brief poolside exchange reminds me how far from practical considerations my training has taken me. A grounding in literary theory and exegetical practice can make things like plot seem trivial. Even so, when I tried to respond to the woman in the bikini, I couldn’t say for certain what was with the goat. And so I read the first story (“Runaway”) once more, this time with a pen, underlining words I thought were important, scribbling notes in the margins. I was hell-bent on nailing down precisely what’s with the goat. Here is the result of my careful investigation: I’ve no idea what’s with the goat. But I am beginning to think my flippant comment to my sister-in-law may have some truth to it—on one reading of the story, it may well be that Munro is offering up some kind of (postmodern?) commentary on T.S. Eliot’s notion of an objective correlative.

Before I explain, three comments:

1) “Runaway” is a brilliant story, as fine a short story as you are ever likely to read. One of the reasons it is a brilliant story is its layered texture. One can easily read it as plot, a schlocky narrative about strained relationships, which leaves one wondering, like the woman in the bikini, if the husband killed the goat. But even a cursory acquaintance with Munro’s writing suggests that plot is not so important a matter, since, in many of her stories, nothing “happens.” Here, the fact of a plot is accidental. But one can also read beneath its accidental shape. There is a an amazing simultaneity of meanings at work here which reminds me of Joyce’s short stories. And, like Joyce’s stories, it comes with an epiphany which is as nuanced and as subtle as any Joyce ever proffered.

2) To the extent that this story is “about” something, it is about power. The characters wield their power by manipulating sexuality and violence—the usual suspects. The positive faces of these tools, love and knowledge, are finally rejected.

3) While I have no interest in applying a psychological analysis (although such an analysis is possible and may well yield a rich vein), nevertheless I adhere to a rule of psychotherapy as I proceed: every word is written for a reason; every word means something. This is not the same thing as asserting that the author intends every meaning that each word might support; I do not succumb to the intentional fallacy. But I do believe that one mark of a good author is this: that even if she were to write a word without turning her mind to its meaning, nevertheless it would belong inextricably to its story. While most writing does not support such scrutiny, I proceed here on the assumption that, in Munro’s work, everything is there for a reason, everything counts.

Runaway tells the story of four people who, taken together, form the supports of an altar on which they sacrifice Flora, the goat, the vessel which bears their sins. Through a description of carpet, Munro gives a backhanded hint that the four must be taken together if they are to be understood at all:

“It was divided into small brown squares, each with a pattern of darker brown and rust and tan squiggles and shapes. For a long time she had thought these were the same squiggles and shapes, arranged in the same way, in each square. Then when she had had more time, a lot of time, to examine them, she decided that there were four patterns joined together to make identical larger squares. Sometimes she could pick out the arrangement easily and sometimes she had to work to see it.”

Munro has warned us what to expect: there are patterns embedded in the fabric she weaves, but we will have to work if we are to discern them. And yes (to answer the woman’s question), in a way that makes sense only in literature, they all kill the goat, just like the murder on the Orient Express.

The protagonist, Carla, is married to Clark. She comes from a solid middle-class city background, but ran away to join Clark, a groomer. Now, they live in a mobile home on a rundown farm with a few horses. Let’s not mince words: they are trailer trash. Carla is described as silly, hinting at both a trivial nature, but also a light touch which complements the heavy-handedness around her. The marriage has grown stale and passionless. Their bed is a “neverland.” To excite her husband, Carla invents an elaborate story of how, when she was helping out at the Jamieson’s, the dying poet, Leon, tried to entice her to do unspecified dirty things. For his part, Clark can only think to use the story to manipulate the now widowed Sylvia into a cash settlement for her late husband’s alleged indiscretions. Throughout most of the story, Clark exudes a thwarted rage, and, like a barometer, his inclement moods are tied to the rain and gloom of the early summer. Over and against Clark and Carla is the story’s other couple, Leon and Sylvia. Leon, the poet, the lion, stands in sharp relief to Clark’s impotent rage. Even from beyond the grave he excites a perverse passion in his neighbours. Sylvia, the forest, has just returned from a trip to Greece. This ushers in a mythos which undergirds the quartet’s relationships. As with the description of the carpet, Munro has already instructed us that our interpretation of the story cannot flower without an understanding of ancient forms: the poet had built his house on the wreckage of an earlier foundation.

Everywhere, there are hints of violence. When Leon was alive, he had “cut paths through the woods” and so we are left to wonder what things he might have done to Sylvia earlier in their marriage. Clark is contrasted with a client, Joy, who boards her horse on their farm. She calls the horse Lizzie Borden. When Carla is tending to one of her own horses, “Lizzie butted in between them and knocked Grace’s head away from Carla’s petting hand.” Indeed, the threat of violence ultimately denies Carla grace, at least the grace we know as moral courage. Clark calls the local hardware store “Highway Robbers Buggery Supply.” Midway through the story, as Carla recalls her flight from her parents to Clark: “She saw him as the architect of the life ahead of them, herself as captive, her submission both proper and exquisite.”

In spite of names like Sylvia and Leon, the quartet do not form types, like directions of a compass. Things are too confused for that, and, perhaps, today’s story-tellers cannot, with authenticity, return to a simpler time when characters could stand for a single principle from beginning end. Here, the characters undergo transformations. Thus, we witness how Carla’s identity shifts as the story progresses. Like the carpet in her trailer, we think the squiggles and shapes of her various relationships are the same, but a closer scrutiny reveals differences over time. We have already read how she committed herself to Clark when she first ran away. But Clark has rendered his bed a “neverland.” His impotence engenders a rage which drives her towards Leon whose bedroom, ironically, has become a death chamber, a neverland of a different sort. We see confirmation of Carla’s shift in Leon’s direction with “her resolute face crowned with a frizz of dandelion hair …. ” In addition, she assumes Leon’s place as the object of Sylvia’s thinly veiled sexual interest; she resembles the boy who rides the horse, the statuette souvenir which Sylvia has brought home from Greece. But she shifts her orientation again. After running away from Clark, she seeks refuge with Sylvia where she showers and puts on some of Sylvia’s clothes.

Just as the characters are tied to one another, so each is tied directly to the goat, Flora. Most obvious is Clara’s identification with the goat: both are runaways. As for Sylvia, she is a botanist, a student of flora. When Carla kisses her on her head, “Sylvia saw it as a bright blossom, its petals spreading inside her with tumultuous heat, like a menopausal flash.” Interesting that this flora is barren. While both Clark and Sylvia separately suggest that Flora may have disappeared to find a billy, “there had never been any signs of her coming into heat.” When Flora appears to Clark and Sylvia, it is as “a live dandelion ball.” Like the menopausal flash, the “vision” of the goat explodes, backlit by a car’s headlights. In spite of the reference to Leon, it is clear that the poet rejects Flora: “Last spring [Sylvia] went out once and picked him a small bunch of dog’s-tooth violets, but he looked at them—as he sometimes looked at her—with mere exhaustion, disavowal.” The poet sees an identification between flora and Sylvia, but he has become impotent and weary and so rejects them both at a single stroke. Finally, we have Clark’s connection to the goat with the obvious hints that he may be the agency responsible for killing the creature. But there is a more remarkable connection: Clark tells us what—or perhaps who—the goat is. As I mentioned earlier, this story comes complete with an epiphany—in the most literal sense. The word “epiphany” comes to us from a Greek word which, when translated literally, means “shine upon.” Read how Clark comes to identify the goat:

The fog had thickened, taken on a separate shape, transformed itself into something spiky and radiant. First a live dandelion ball, tumbling forward, then condensing itself into an unearthly sort of animal, pure white, hell—bent, something like a giant unicorn, rushing at them.

”Jesus Christ,” Clark said softly and devoutly. And grabbed hold of Sylvia’s shoulder. This touch did not alarm her at all—she accepted it with the knowledge that he did it either to protect her or to reassure himself.

Then the vision exploded. Out of the fog, and out of the magnifying light—now seen to be that of a car traveling along this back road …

The foundation of this house is as rich as western culture itself—Greek mythology buried beneath a layer of Christian imagery.

There remains one great myth to consider: the story of Adam and Eve, the garden of paradise, the apple and temptation. This myth first presents itself in Carla’s dream. The goat appears to her with an apple in its mouth, then she leads Carla to a barbed-barrier and “just slithered through like a white eel and disappeared.” The patterns in the carpet are squiggles. When Sylvia had taken in Carla to help her make a break from Clark, she let Carla take a shower. “She had put out a fresh cake of apple-scented soap for the girl’s shower and the smell of it lingered in the house …. ” Then, at the story’s end, when Carla learns that the goat had returned, that Clark had known this, that the goat was nevertheless still missing, “she was inhabited now by an almost seductive notion, a constant low-lying temptation.” This is the temptation to learn the truth, to walk to the edge of the woods where the turkey vultures have been perching, and discover for herself whether it is the goat which has been their dinner. She imagines the gruesome scene. She imagines holding the goat’s skull. “Knowledge in one hand.” Carla resists temptation. But her fortitude is not virtuous, for she deliberately chooses to remain ignorant. Better to smooth things over, to get on with the appearance of working marriage, than to discover the truth.

At the beginning of this little survey, I had mentioned something about the story being a postmodern commentary on Eliot’s objective correlative. It seems clear that the goat is the objective correlative. But where is the postmodernism? Maybe the postmodernism lies in the fact that, in its conclusion, the story cannot ground itself firmly in any one layer of all the layers which speak to the story’s movement, not even in skepticism. Is the goat a tempter? Odd that this is a temptation to do nothing. Is the goat a redeemer, buying freedom with its blood? Yes, when the story ends, the sun is shining and Carla and Clark have “saved” their marriage, but Carla’s return feels too much like compromise to be much of a redemption. Is the goat a harbinger of doubt? Not exactly. Even an anti-resolution is a resolution of sorts. Instead, we are left with a big nothing. Not the nothing of nihilism nor of some clearly articulated philosophy. Just the nothing of our world’s well-considered refusal to make anything decent of itself.