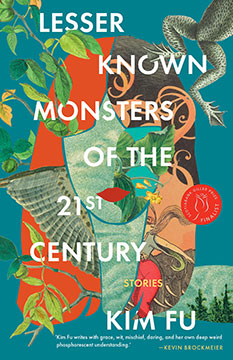

Kim Fu’s Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century is one of two story collections to be shortlisted for the 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize for fiction. Hers is the sort of collection you’d expect to appear if you were to set a book of Etgar Keret stories on a shelf next to a book of Zsuzsi Gartner stories then turned out the lights and left them to fool around in the dark. As we know from the science of genetics, the offspring inherits in equal measure the traits of its parents. The same rule applies to the genetics of story telling.

From Keret, Fu’s stories acquire a sense of magical mischief that opens doors to a dark interior experience. From Gartner, they acquire an ironic preoccupation with the aesthetics of banality which is the beating heart of middle-class North American suburbia. While, in Gartner, this preoccupation finds its highest expression in the appearance of zombified teenagers, Fu offers no place for zombies in her stories. As the title of her collection indicates, she is more concerned with lesser known monsters, a stolen doll that proves indestructible, an infestation of june bugs, and a giant amorphous blob of single-celled organisms floating around the Pacific Ocean.

Kim Fu often conceals the Etgar Keret influence by swapping magical premises for tropes borrowed from science fiction. And why not? Given Arthur C. Clarke’s famous observation that the technology of a sufficiently advanced civilization will be indistinguishable from magic, the reader can safely assume that a sufficiently advanced science fiction will be indistinguishable from magical realism, and vice versa. So we have the opening story, “Pre-simulation Consultation XF007867” in which a prospective customer argues with a customer service representative about why he cannot purchase a simulation that would allow him to spend time with his recently deceased mother. “Time Cubes” features a product introduced just in time for the Christmas rush, a terrarium with a knob that allows the user to age (or de-age, depending on which way you turn the knob) whatever living thing you find inside the terrarium, whether a plant or a frog. A depressed woman has casual sex with the inventor and, well, the result is a tale in the same vein as Prometheus stealing fire from the gods, or Pandora’s box.

At other times, the Zsuzsi Gartner influence predominates, as in “The Doll” when the narrator’s mom discovers the neighbour, Mr. Mullins, hanging from a beam in the carport. His suicide is the culmination of a grief that began when his family died of carbon monoxide poisoning in their mid-century ranch style home, a house “specifically for the dreamless, signifying nothing.” On a dare, the neighbourhood children enter the taped-off house, now slated for demolition and redevelopment as infill housing. They poke around the suburban ruins like aliens investigating the post-Anthropocene, trying to make sense of the mass extinction that has left behind so much stuff. Once inside, a further dare sees one of the intruders take a doll that belonged to the now-deceased Mullins daughter. Naturally, the doll creeps out the children and we half expect a Stephen Kingish ending: the doll turns malevolent and each of the trespassing children meets a gruesome end. But that isn’t Kim Fu’s game. The doll proves malevolent, but for a different reason. The children try to destroy it. They chop it into bits and each child is tasked with destroying their bit. The narrator tries his best to get rid of the left arm, but every time he moves, from college dorm to his first apartment and beyond, the arm ends up in a moving box and comes with him. In a way, the story is a parable of our consumerist lifestyle. In a world of forever chemicals and anaerobic waste sites, maybe the greatest monument to our presence on planet Earth won’t be the pyramids or the temples of Ankor Wat, but the discarded plastic toys we bought our children to shut them up.

And then there are stories where we find traces of both influences wound together like the double strands of a DNA molecule. “Liddy, First To Fly” tells the story of prepubescent girls in a school yard during recess who discover that the most precocious of their in-group is sprouting Hermes style wings just above the ankles. The story sets the magical element of sprouting wings (reminiscent of an episode in One Hundred Years of Solitude) against the backdrop of suburban banality. In the same way, we have “Twenty Hours” featuring a new technology which allows the owner to “print” a fresh self in the event that their current self should, for whatever reason, cease to exist. A couple buy the product so that they can occasionally murder one another without repercussions. In answer to the question how can an ordinary couple afford such an expensive piece of hardware? we learn that they are quiet millionaires in the manner of David Chilton’s The Wealthy Barber. They are “the misers among you, in our quaint three-bedroom house in the suburbs, unrenovated since the 1990s, one modest hatchback car between us, our big-box store generic clothes, our outdated phones and computers.” Then again, what sort of people do we become when we can poison one another’s McDonald’s takeout with impunity?

Kim Fu’s Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century is a wonderful collection of entertaining stories that speak directly to North American culture at this specific historical moment. Personally, I find it a little lighter than the other nominees for the Giller Prize and don’t see it as a contender. Even so, it’s a pleasurable read. If you enjoy the stories of Kelly Link, Etgar Keret, or Zsuzsi Garner, you’ll enjoy these.