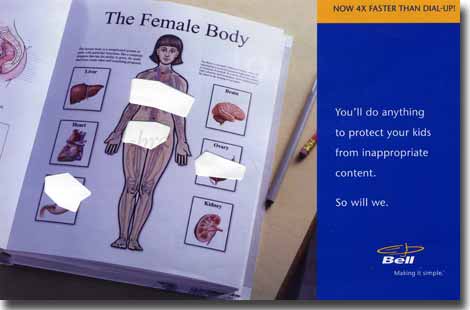

Just as I was ruing the plight of the human mind at the hands of publicly instituted censors, I received this delightful piece of unsolicited advertising in my mailbox. “You’ll do anything to protect your kids from inappropriate content.” And beside the copy is an example of the kind of inappropriate content I might wish to hide from my children—the female body. Just when I thought it was safe for my children to open their eyes, women went out and got bodies!

What is it, precisely, about a woman’s body that might prove to be so offensive? I believe in the validity of the feminist push to prevent the objectification of woman and the violence which such objectification sometimes produces—but this goes too far. It promotes a different (though no less corrosive) disrespect for the female form. Are medical drawings of breasts so offensive that we must snip them from our textbooks? I thought that the fact of breasts was one of the features which defines us as a species of a particular class. We are mammals. The fact of breasts also reminds us of our kinship with the natural world. And it reminds of us of our most primal need for nourishment. It symbolizes what we crave most and what we desire beyond all else—love. Evidently, Bell Canada disagrees with me.

Some Americans are critical of Canada for its failure to establish an institution comparable to the American Federal Communications Commission, but we are much too subtle to entrust such a grave responsibility to a public entity. Americans should genuflect before us and kiss our rings, for we have used private enterprise and the free market (quintessentially American approaches) to excise all the smut that pollutes the weak minded and the young. Corporate communications services are merely meeting the public demand for an antiseptic world. The analogy to sterilization and cleanliness is apt. As public health officials are now discovering, if we are too clean, then we never have the opportunity to develop our natural immunities and, at the same time, we promote conditions that favour more resistant strains of disease. In the same way, if we protect our children too much, they never gain the opportunity to exercise critical reasoning when, inevitably, they encounter images which are more deeply disturbing than medical illustrations.

I worry that if we entrust external (external to the family unit) entities, whether public or private, with the role of evaluating content, then we reveal our own inadequacies. Rather than be near at hand when our child first stumbles upon a pornographic web site, when we could spend a few minutes talking about what is wrong with such a site, we prefer to abdicate our role as active and engaged parents.

My final observation is this: why does pornography exist in the first instance? Who supports it? As Pogo says: “We have seen the enemy and it is us.” Odd that the people who privately create the demand for the porno product are the same people who publicly create the demand for protection from it.