The judge gave Jackson time served plus community service. Since Jackson had half an English degree behind him, the judge let him do his community service at the Oak Ridge Rest Home. The staff there needed help with a special project. They wanted to interview all the residents—or at least all the residents who were right in the head—to produce a book of bios and memories and whatnot. It would be therapeutic for all the old folks to reminisce about the good old days. Jackson told the judge he didn’t want to interview the boring ones; he’d only do it if he got to interview a Nazi hunter. The judge told him he’d interview whoever the staff assigned to him and he’d damn well like it. Jackson said thank-you the way his lawyer told him to and left the courtroom a more-or-less free man.

The staff paired him with an old guy named Norm who lived in a tiny apartment, although apartment is probably an exaggeration. It was more like a cubicle, with room for a single bed and shelves full of pictures. There were pictures of children and grandchildren who never visited. And there were pictures of an old woman. Norm said the woman was his wife, Mildred. He didn’t specify whether Mildred was dead or just living down the hall in another cubicle. He didn’t specify whether things belonged to the past or to the present either. Everything blurred together. Norm’s memory turned time into one big lump.

The room was stuffy and it smelled as if Norm hadn’t taken a bath in weeks. Jackson tried to open the window but it stuck. Jackson suggested they go outside for their interview. It was June and warm and the fresh air would do the old man good. Norm shuffled along with his walker and when they passed through the front doors, he slipped Jackson a ten and told him to go across the road for a pack of Marlborough’s.

“I’m dying for a smoke,” Norm said. “They don’t let you smoke in there. They say it isn’t healthy. Like that would make any goddam difference at my age.”

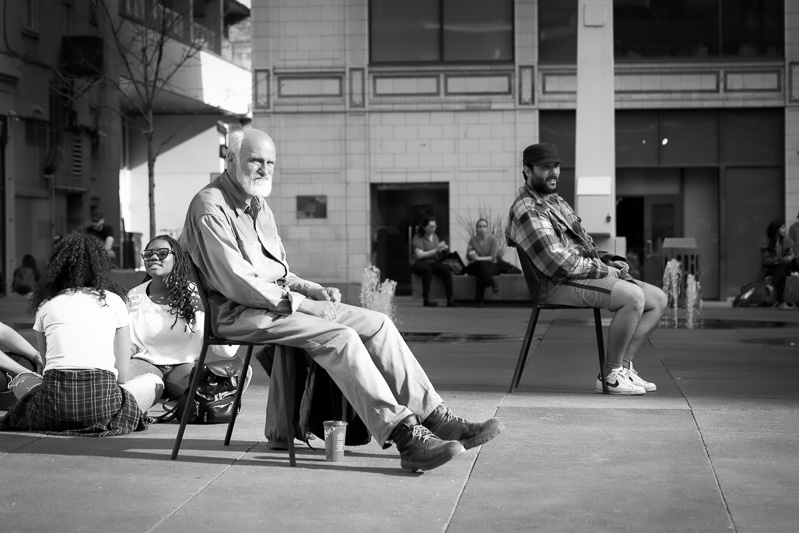

While Jackson went across the road for a pack of cigarettes, Norm shuffled down the road to a parkette where he settled on a bench in the shade. When Jackson got back from the store, he handed Norm the pack of cigarettes and kept the change for himself. Norm didn’t notice. He was too busy trying to get the cellophane wrapping off the pack of cigarettes. He didn’t notice the sun shining on the grass. He didn’t notice the bed of flowers behind the drinking fountain. He didn’t notice the birds twittering overhead in the tree. All he noticed was the pack of cigarettes that fumbled onto his lap and then onto the ground between his feet.

“Damn,” the old man said as he reached through the frame of his walker.

It was more than Jackson could bear. He picked up the pack, tore off the cellophane, whipped out a cigarette and lit it between his own lips before passing it to the old man. “So I’m supposed to interview you,” he said.

“Eh?”

“Your life.”

“What about my life?”

“I’m supposed to interview you about your life.”

“What the hell for?”

“They’re making me do it.”

“Lucky you.” And the old man took a long drag on the cigarette, then exhaled until his head was lost in a cloud of smoke.

“So you were a Nazi hunter?”

“A what?”

“A Nazi hunter.”

“Whatever gave you that idea?”

“They promised me a Nazi hunter, like the Jew Bear.”

“Like the what?”

“Like in the movie. You know. Where the guy bashes Nazi heads with a baseball bat.”

“I grew vegetables on my father’s farm.”

“You never saw any action?”

“I grew tomatoes and beets and such.”

“But I thought—”

“And I milked the cows too.”

“So you never killed any Nazis?”

“What? You don’t think growing food helped the war effort? How d’you think our boys would’ve done without any food?”

Jackson shrugged. He took the pack away from the old man and lit a cigarette for himself.

“Then after that I went to normal school.”

“Normal school? What the hell is normal school?” Jackson imagined that’s where they put mental defectives and turned them into ordinary functioning citizens.

“Normal school’s what they used to call teacher’s college.”

“So you taught kids?”

“Thirty-five years.”

“And you never killed any Nazis?”

“Sorry to disappoint you.”

The two men—one young, the other old—smoked their cigarettes down to the filter, then stubbed out the butts under their shoes. Norm wanted to smoke another cigarette, but when he went to get it out of the pack, something funny happened to his arm. It flopped around at his side like a rubber hose. He ordered his arm to light another cigarette, but it refused to obey. He asked the boy to help, but all the words came out in a slur, like he was drunk, only worse. The left side of his face felt like melted wax. When he looked up at the tree, and at the sky beyond the tree, it all went fitzy the way an old black and white TV goes when it’s stuck between channels. He slumped over his walker, and even though he knew inside himself that he was still him, he couldn’t do anything to tell this boy that he was still him. The boy stared at him for a while, poking at his shoulder, then pocketed the Marlborough’s for himself and walked away.

After a while—maybe a few minutes, maybe a hundred years—the boy returned to the parkette with a staff member from the Oak Ridge Rest Home. She was a nurse and knew what to do in situations like this. The first thing she did was check Norm’s pulse. She said Norm was still alive.

“We were just sitting here talking,” Jackson said, “then he went all funny.”

The nurse called an ambulance and they carted Norm away to the hospital. They kept him in the hospital for a couple weeks. Even though they let him come back to the Rest Home, he was never right after that. When Jackson visited him, his head lolled to one side, and none of his words made sense. The staff said they could get someone else for Jackson to interview. But Jackson said no. He had enough material from Norm to write up something for the book. He promised he’d have it in time for publication.

Jackson was true to his word. This is how the bio started:

Oak Ridge Rest Home has a hero in its midst. Its very own Norm Woodrow served his country during the war. He belonged to an elite unit that hunted Nazis and brought them to justice. I’m proud to have known Norm. Even though horrible things happened during the war, it’s reassuring to know that there were decent men like Norm protecting our country, making it a safe place for people like me to grow up in.

The staff loved Jackson’s bio. Wasn’t it amazing, they said, how you could work for years with old folks and have no idea what had gone on in their lives when they were young. Mostly, the staff saw wizened has-beens who had frittered away their lives. It just goes to show you, they said, and they thanked Jackson for setting them straight.

Well, that took care of twenty hours. Jackson still had eighty hours of community service left before he was off the hook. He wondered if Oak Ridge had any astronauts. He’d love to interview an astronaut for the next volume.