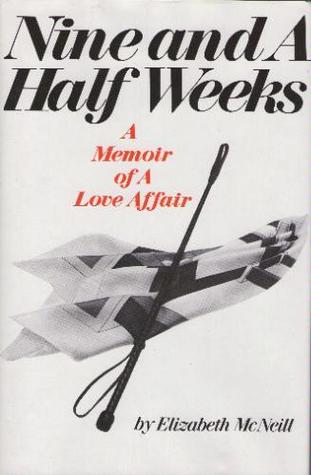

Elizabeth McNeill’s erotic memoir of a love affair is celebrated for the fact that it’s told from the submissive’s perspective in an SM relationship. The unnamed man slaps, cuffs, spanks, whips, beats, humiliates the narrator who leverages the pain to a heightened desire. At least that’s how the novella-length memoir is celebrated. My take on the book is that it has less to do with sex than with shopping.

Shopping is the backdrop for the couple’s first encounter. The narrator (for convenience, I’ll call her Elizabeth) is out on a Sunday afternoon with an old friend shopping “at one of the stalls selling old clothes, old books, odds and ends labeled “antique,” and massive paintings of mournful women, acrylics encrusted at the corners of pink mouths.” She’s debating aloud whether or not to buy a lace shawl. A man whispers in her ear that she ought to buy it; someone else might snap it up. The lover’s first words: an encouragement to shop.

On Thursday, Elizabeth finds herself “trapped” in the man’s bedroom while he deals with the concerns of a panicky colleague. As the men talk in the living room, she takes advantage of her confinement to survey her new lover’s possessions. The enumeration—with special attention to clothes, laundry habits, and an arrangement with Brooks Brothers—proceeds over eight pages. When the men have finished their conversation, the lover returns to his bedroom. They make love in the space of a single sentence. Afterward, they eat three slices of blueberry pie and drink a bottle of Chablis. He slaps her on the face and, the following day, as she recalls the reflected image of his hand print rising on her skin, she notes that “[d]esire sweeps over me so intense it makes me nauseous.”

Maybe I should revise my claim that the book is about shopping. More generally, it’s about consumption. Food holds almost as much importance as shopping. On Saturday morning, the lover appears “holding a scuffed metal TV tray with a plate of scrambled eggs, three toasted English muffins, a pot of tea, one cup. A peeled, sectioned orange sits in a small wooden salad bowl.” As he delivers breakfast, he announces that they have to go to Bloomingdale’s. We then have five pages of shopping for a bed. A few days later, the lover surprises Elizabeth with a silk-covered address book she had admired at Bloomingdale’s.

The next Saturday they’re out doing errands (i.e. shopping) when the lover hails a cab and they end up at a hunting store in Brooklyn. There, he finds a riding crop, but before buying it, he tests it. In front of the clerks, he raises Elizabeth’s skirt and strikes the inside of her thigh. Satisfied with the result, he makes his purchase.

As the lover escalates the game, so he escalates the shopping. On a Friday afternoon, he directs Elizabeth to a hotel room where she finds the bed heaped with packages “[n]ot gift-wrapped, but what one spills on a bed after a day of shopping, just before Christmas.” There’s a shirt from Brooks Brothers, socks from Altman’s, even hairpins from Woolworth’s, all the components of a disguise. She is to cross-dress, passing as a man to meet her lover in the hotel bar. The evening culminates in a beating and anal sex.

The next morning, the lover appears with a bag from Bendel’s. When Elizabeth is released from her handcuffs, she opens the bag and finds a black lace garter belt and stockings. The lover then describes at length his dealings with the matronly saleswoman who sold him the items. He follows up with a shoebox from Charles Jourdan. Inside is a pair of pumps with improbably high heels. This becomes part of the foreplay. He forces her to crawl on the floor and beats her across the back of the thighs with the riding crop. For the first and only time in their relationship, they come together.

Elizabeth explains the appeal of this relationship:

For weeks on end I was flooded by an overwhelming sense of relief at being unburdened of adulthood. “Would you let me blindfold you?” had been the first and last question of any importance asked of me. From then on, nothing was ever again a matter of my assent or protest (though once or twice my qualms became part of the process: to make my addiction clear to me); of my weighing priorities or alternatives—practical, intellectual, moral; of considering consequences. There was only the voluptuous luxury of being a bystander to one’s own life; an absolute relinquishing of individuality; an abandoned reveling in the abdication of selfhood.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that an SM relationship should play itself out in the proximity of shopping. Nor is it a coincidence that the narrative (and the shopping) should belong to the submissive. We tend to think of shopping as if it falls on the dominant side of our consumer relationships. It is something we actively do. We make choices one way or another. It is an expression of our agency. Even cultural critics who ridicule the idea (widely held in 21st century North America) that consumerism is an expression of democratic agency, nevertheless assume that it is at least possible to understand shopping as an expression of some kind of agency.

But a book like Nine and a Half Weeks offers a clue as to why it might make more sense to think of shopping as an act of submission. We see it in the phrase quoted above: “the voluptuous luxury of being a bystander to one’s own life; an absolute relinquishing of individuality; an abandoned reveling in the abdication of selfhood.” In the shopping dynamic, the vendor acts upon the consumer through advertising, pitches, salesmanship. The act inflicts pain as a feeling of inadequacy, a sense of lack in one’s life, a general unhappiness. The pain elicits desire, and the desire, in turn, leads to a consummation.

The consumer is “unburdened of adulthood.” The vendor creates an experience which grants the consumer permission to make choices without having to think of their consequences. There is no worry about externalities in the exchange: pollution in the manufacturing process, exploitation of labour, tax evasion, revenues that fund organized crime. The purchase of mass-produced goods protects the consumer from individual differentiation and the personal responsibility that such differentiation would require. For a time, the consumer/submissive gets to live in a Disney bubble of (un)consciousness where everything is done for her—eating, dressing, thinking—and even the pain is fun.

The problem with the SM relationship is that, as the title implies, it lasts only so long. It’s unsustainable.

One wonders if the same holds true for shopping.