Whenever I read novels, I find myself attuned to bodily functions. This predilection began years ago with Milan Kundera’s famous shit rhapsody in The Unbearable Lightness of Being. He made a simple claim: kitsch is the denial of shit. By contrast, art embraces shit. Following Kundera, we can safely take shit for an objective correlative; it stands for all the unpleasantness we must undergo in our daily lives—squatting over the toilet, cleaning up after sex, climbing steep slopes, shivering when we step outside in the winter, hunger pangs, disappointment, money troubles, sickness, and, finally, death. Art is not art if it does not incorporate lived experience in all its fullness. It comforts us by acknowledging that we share in that experience. It offers guidance so that we may reconcile ourselves to that shared experience.

Kundera’s philosophy of shit found perhaps its highest expression in David Foster Wallace’s long story, “The Suffering Channel.” The story’s action is driven by the publication deadline—September 10th, 2001—of a lifestyle magazine with head offices in the World Trade Center. The reader knows that the magazine will never make it to the stands. We feel the weight of an approaching disaster that will etch itself on the American zeitgeist and traumatize a global city. Today, an event that served as a touchstone for a generation will meet its equal in Covid-19. But today’s event is different. This disaster is global. Every human alive today will feel its effect. And this time, America will not be able to claim an exceptional suffering.

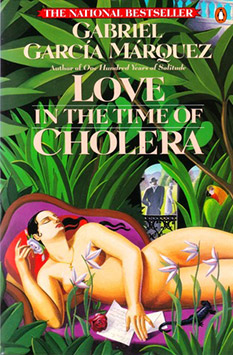

In a fantasy of influence, I would like to think that somehow Gabriel García Márquez read Milan Kundera and incorporated his idea into Love in the Time of Cholera. The English translation of The Unbearable Lightness of Being was published in 1984, a year before Márquez’s novel, so such an influence, however unlikely, is possible. It’s more likely that Márquez felt in his heart what Kundera expressed in his drier intellectual prose. Early in the novel, Márquez writes of the decadence that has settled upon the newly independent but unnamed country: “At nightfall, at the oppressive moment of transition, a storm of carnivorous mosquitoes rose out of the swamps, and a tender breath of human shit, warm and sad, stirred that certainty of death in the depths of one’s soul.” Kundera would approve. Not surprisingly, the lover, Florentine Ariza, the man who, for more than 50 years, clings to the hope of uniting in love with Fermina Daza, suffers from constipation. As his family doctor once observed: “The world is divided into those who can shit and those who cannot.”

The other bodily function which figures in this story is vomit. The early literary history of vomit treats the act of emesis as a symbolic response to excess. In the popular imagination, we tend to trace the vomit/excess association to ancient Rome. We imagine emperors hosting wild orgies in which guests vomited up the contents of their stomachs so they could go on eating. In fact, ancient accounts of vomit are rare and orgies of the sort portrayed in Hollywood films are impossible to substantiate. The most interesting vomit account from Ancient Rome concerns Julius Caesar. Thanks to Cicero, it is well documented that he was on a physician-prescribed course of emetics. In the year before his death, Julius Caesar dined at the home of Deiotarus of Galatia. Part way through the meal, he excused himself to vomit. It turns out that assassins were waiting for him in the bathroom. However, perhaps because he was feeling ill, Julius Caesar ignored the servant’s directions and vomited in the host’s bedroom instead. In that way, he put off his assassination by a year.

In modern times, one of the chief advocates of the vomit/excess nexus is Aldous Huxley whose Antic Hay (mis)appropriates the term vomitorium to describe the room where gastronomic orgies occur. In fact, the vomitorium is an architectural term to describe the exit beneath a tier of seats through which a crowd might “vomit forth” from a Roman amphitheatre. However, Will and Ariel Durant adopted Huxley’s erroneous etymology in The Story of Civilization and the orgiastic account of ancient Rome became entrenched in the modern imagination despite an absence of evidence.

In some contexts, vomit may not hold any symbolic value per se. Just as vomit can be the symptom of an underlying illness, so the appearance of vomit in a literary context can be the invocation of whatever principle the illness represents. Typically, illness in literature is connected to the passion of love. Like the Eddie Cooley/Otis Blackwell song, the lovers infect one another with a fever. My favourite literary instance of this is found in Brian Fawcett’s 1992 Gender Wars. The narrator is delivering oral pleasure to a young woman when he is seized by an urge to vomit. Since it would be rude to stop before the woman has climaxed, but equally rude to vomit into the woman’s hoo-haw, the narrator finds himself in a pickle. He suppresses the urge to vomit just long enough to complete his task, then rolls onto the floor and vomits into a hot air register.

In Love in the Time of Cholera, vomit operates both to symbolize excess and to signal the fever of love’s passion. Excess is simpler to understand. Florentino Ariza’s rival in love, Dr. Juvenal Urbino, had been drinking liqueur and in the presence of his mother and sisters “fell flat on his face in an explosion of star anise vomit.” The drinking, of course, followed a visit to the object of his love, Fermina Daza. Not to be outdone, Florentino Ariza downed a litre bottle of cologne, which sailors sold as contraband, because the odour reminded him of Fermina Daza. His mother “who had waited for him until six o’clock in the morning with her heart in her mouth, searched for him in the most improbable hiding places, and a short while after noon she found him wallowing in a pool of fragrant vomit in a cove of the bay where drowning victims washed ashore.”

Vomit is also a symptom of cholera and, as one can infer from the novel’s title, cholera is important. Márquez takes pains to ensure that we understand: in the world of his novel, cholera is inextricably tied to love. When a young Ariza first encounters Fermina Daza, we have this:

After Florentino Ariza saw her for the first time, his mother knew before he told her because he lost his voice and his appetite and spent the entire night tossing and turning in his bed. But when he began to wait for the answer to his first letter, his anguish was complicated by diarrhea and green vomit, he became disoriented and suffered from sudden fainting spells, and his mother was terrified because his condition did not resemble the turmoil of love so much as the devastation of cholera.

From this, we learn that “the symptoms of love were the same as those of cholera.” Fermina Daza rejects the advances of Florentino Ariza and so “he contracted the fever of many disparate loves in his effort to replace her.” His mother observes that “‘[t]he only disease my son ever had was cholera.’ She had confused cholera with love, of course, long before her memory failed.”

To the young Dr. Juvenal Urbino, cholera has a more prosaic meaning. He rounds out his medical education with studies in Europe where he learns the latests (turn-of-the-century) scientific techniques. When he returns to his unnamed hometown, presumably in Colombia, he is determined to eradicate cholera by introducing modern sanitation, public health initiatives, and by draining a nearby swamp. From an old and wealthy family, Urbino is influential and unapologetically rational. Fermina Daza’s father sees an opportunity and pressures his daughter to marry the young doctor. Although she is pursued by Florentino Ariza, she gives in to her father’s wishes and enters into a sensible marriage. It is not an unhappy marriage, but it is not a passionate arrangement either. Nevertheless, it endures for more than 50 years when Urbino suffers an undignified death, falling from a ladder while trying to capture his escaped parrot.

The ever patient Florentino Ariza sees his chance and makes overtures to the widow Fermina Daza. At first, she rebuffs him, just as she did more than half a century before. There is nothing at all rational about carrying on a relationship with this man. For one thing, he is bald. For another, he is myopic. Worse still, he has had all his teeth removed. Worst of all, he is extraordinarily promiscuous. As readers, we are privy to this fact, but thanks to his discretion, Ariza has ensured that his love will never know. He has even gone so far as to carry on an affair with a minor who commits suicide when she learns of his passion for Fermina Daza.

Eventually, Fermina Daza relents, not because Florentino Ariza wears her down, but because she comes to recognize her feelings and wishes to give them play in her life even if it is now the life of an elderly woman. Her marriage to Urbino required her to make do. With Ariza, there is the possibility of something more.

Over the years, Ariza has risen through the ranks of a riverboat company until he effectively controls the business. He persuades Fermina Daza to join him on a river cruise and this creates an opportunity for their relationship to blossom. It is a voyage of excess. Perhaps the most egregious excess is perpetrated by the riverboat company which has denuded the surrounding forest to fuel its boats and, thanks to the resulting erosion, has rendered the river almost unnavigable. As they approach their home on the return trip, they change their minds. Instead of settling into the predictable life of aging lovers, they hoist the yellow flag that warns of a plague on board, and they sail away.

In the human imagination, a disease is never just a disease, a plague is never just a plague. Humans cannot help but ascribe meanings that lie far beyond the medical descriptions of these events. To the ancient Israelite, plague was a sign of moral failure. Albert Camus’s novel, The Plague, points to our complicity in an unjust social order. In Don DeLillo’s White Noise, the airborne toxic cloud suggests a culture of death at the heart of American consumerism. In Gabriel García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera, the infection twins two of life’s most unreasonable proposition: the threat of death and the passion of love. I have no doubt that in time Covid-19 will assume cultural meanings all its own. It is too soon to know what those meanings will be. For now, the only thing we can know for certain is that we will have to rely on our writers and artists for that answer.