Increasingly, I find myself drawn to the observation that the motivating force of contemporary mainstream culture (as evidenced by its art, entertainment, politics, literature, religion, economics) is a species of literalism. Sometimes I feel like the last uninfected survivor in a zombie flick. All around me, ravenous vacant-eyed humanoids already infected by the literal virus totter towards me salivating for a taste of my brain.

Why the proliferation of literalism? As we shall see, I think Why? is the wrong question. It’s not that I think Why? is the wrong question in this instance; I think Why? is the wrong question in any instance. Why? is the first pustule on the flesh of a freshly infected zombie. When three-year-olds ask Why? Why? Why? Why? their parents should muzzle them until they can come up with a better interrogative pronoun. I have no idea why the proliferation of literalism. Even if I knew the answer, I’d never share it with you.

As a topic of conversation, literalism finds its greatest play in religious concerns. The literalists are Bible-thumping Christian conservatives reduced to caricature by self-identified liberal Christian-types who waste an extraordinary volume of breath outlining what’s wrong with Biblical literalism while remaining deliberately vague when asked to frame their own views in positive terms. But in the 21st century, religion is a marginal activity, so it’s easy for the secular majority to persuade itself that literalism is likewise a marginal activity. I don’t share the secular majority’s view of things. I view literalism as rampant in the mainstream film industry, the mainstream publishing industry, in the mainstream discursive practices of political wrangling, in health care, in industry, in charitable fundraising, in advertising … the list isn’t endless; it’s only as long as the sum of human activity.

A good point of entry into a discussion of literalism, or at least as good as any other, is through the door of interpretation. So often in religious debates, we hear liberals speak (disparagingly) of “literal interpretation.” It’s a dumb phrase – a classic question-begger – that reveals what’s at stake. The phrase “literal interpretation” assumes a conclusion to the very matter under debate. Fundamental to the literalist position is the belief that interpretation is unnecessary; it’s possible to communicate with unmediated speech, to mean exactly what you say, to apply your words (or images or film clips or paint daubs) with such precision that you obviate the need for interpretation. And so, for example, because God is the author of the Bible, and because God is no fool, God must have authored the Bible to say exactly what He intended it to say, and in such a way that when we read those words, we can understand them on their face.[1]

The typical argument from those who reject literalism is that everything requires interpretation, that it’s impossible to encounter the world in an unmediated state. Everything we encounter, whether it’s the words in the Bible or the stars in the night sky, must pass through our interpretive faculties. The liberal Christian-type hears the fundamentalist’s take on the creation passage(s) in Genesis, or the Flood, or the resurrection of Jesus, or the end times suggested by the Book of Revelations, and says something like: “Oh well, they’re meant to be understood metaphorically.” Or: “Those passages have undergone a process of demystification; let me explain what’s really going on.” The problem with this kind of answer is that it doesn’t answer anything; it only defers the question. The answer introduces some form of interpretive machinery, like text or form or redaction or historical or literary criticism, and then goes on a long excursis, explaining just how the interpretive machinery works in this particular instance. But the very act of explanation assumes that the words used by the explainer/interpreter can, ultimately, be understood on their face. The religious fundamentalist and the liberal Christian-type share an assumption about what it is possible for words (or any other medium for that matter) to communicate. A liberal Christian-type is a literalist at one remove.

Literalism affirms the possibility of an unmediated connection between subject and object. The medium effaces itself, allowing the object to leave a direct impression on the observing mind. Fundamentalist religion provides the paradigm: the words of scripture mean exactly what they say, nothing more, nothing less. But we can enumerate any number of secular examples that illustrate the same affirmation:

Pornography:

I have no idea what makes it art when we portray human beings engaged in the various activities that lead up to and consummate sexual intercourse. But the portrayals we count as art include one sine qua non. All these portrayals seek in some way to obscure our view of the act. The medium inserts itself between our watchful eyes and the naked down-and-dirty of it. Maybe the act is implied through a clever synecdoche. Or maybe the consummation is deferred. Or maybe the bodies, although explicitly represented, suggest something else e.g. sex as metaphor for spiritual union.

Pornography strips away the implied, the deferred, the metaphor, and leaves us with the act as it really is. The camera is never too close for the cum shot. The lights are never too bright for the penetration shot. Pizza delivery boy scenarios notwithstanding, the actors are unburdened by narratives. Their job is to give the camera the thing itself, nothing more, nothing less. In his piece on the Adult Video News awards, David Foster Wallace shares H. Hecuba’s observation that “the relation between a Calvin Klein ad and a hard-core adult film is essentially the same as the relation between a funny joke and an explanation of what’s funny about that joke.”[2]

Like the liberal Christian-type who demystifies religious texts while trying to explain what it is that fundamentalists fail to “get” with their literal account of things, the porn producer, uh, desacralizes sexual love, or whatever, while trying to explain what really goes on in the obscurity of the shadows.

Homiletics:

As you may have guessed already, I haven’t much patience for religion that tries to explain itself. The clergy at the pulpit is a pornographer and the chancel is his bedroom. The point of the sermon is to help the congregation “get” the joke by explaining in a self-effacing unmediated way what it all means, literally, of course. The result is a literalism that patronizes by pretending to be something else.

Publishing:

Most of what we call contemporary literature engages us in precisely the same way. James Wood has coined the phrase “commercial realism” to describe the current taste in literary fiction which treats mimesis – the extent to which the portrayal matches its real-world referent – as its chief measure of quality. Never mind that such a way of thinking is a step backward to some of the earliest stabs at a theory of aesthetics. Surely we’ve come up with some better accounts of things in the intervening 2500 years. Commercial realism – and realism of any sort – is a species of literalism. It assumes the possibility of an unmediated connection between the world and the reader. The text (as portrayal of the real world) functions like an aesthetic superconductor, throwing up no resistance between subject and object. “Bad” writers are bad because their portrayals produce resistance. Their descriptions don’t convince us. We have trouble imagining the scenes they describe. Or their characters aren’t believable. We can’t empathize with them. Their motives wouldn’t pass muster if examined by a certified psychologist. The dialogue is stilted. Real people living in that place and time and enjoying a given socioeconomic status would never talk that way. “Good” writers are good because their portrayals minimize resistance. Their work feels natural. It feels natural because it portrays the world as we know it and we know it because it’s real. We feel it literally.

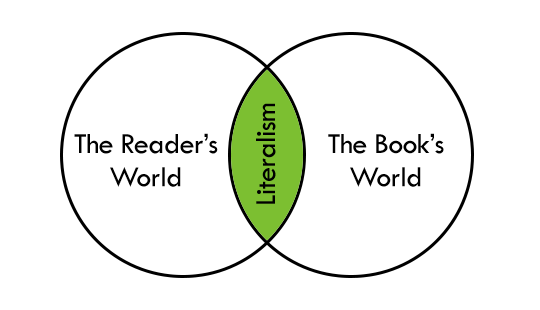

We can represent this with a Venn diagram:

In the diagram, there are actually four circles, but three are co-extensive. The Reader’s World completely overlaps The Real World which completely overlaps The Author’s World. The Book’s World is the result of the author’s mimetic efforts. The overlapping area represents the degree to which the author succeeds in producing a realistic portrayal. I’ve called this overlap Literalism. The more literal the representation, the better the book. That’s pretty much how it works in the (real) world of commercial realism.

Film:

Commercial (mostly Hollywood) film is more susceptible to literalism than is publishing. When you read a novel, there comes a moment when you notice that you’re reading a sequence of words and, unless you’re reading the illustrated edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, there are no visual cues referring you to the real world you occupy. You realize that there isn’t really a rabbit hole gaping at your feet; you’ve colluded with Lewis Carroll to perform an imaginative trick that produces the rabbit hole. It is possible that the rabbit hole has a referent in the real world, but you can do without it after all. But when you watch a film, it’s easier to be persuaded that such an imaginative trick is unnecessary. You see an image of a rabbit hole and you say: oh look at the rabbit hole. You forget that it’s a representation of a rabbit hole.

An easy way to recover the awareness that you’re participating in an imaginative trick is to watch the narrative sequences embedded in recent video games. New titles like Uncharted aspire to a kind of convergence between the gaming and film industries. Using motion capture technology, video games offer complex film narratives that give a context for the treasure you’re stealing or the foreign-looking soldiers you’re blowing up or the zombies you’re decapitating. As processors get faster, 3D rendering speeds up, meaning irregular shapes can be formed with more polygons, meaning objects can be given more detail. Dirt is grittier. Leaves are veinier. Hair is hairier. Meanwhile, filmmakers like James Cameron use motion capture technology to converge from the other direction (think Avatar). Films get game spin-offs. Games get film spin-offs. And both spin-off action figures, soundtracks, and underwear. The goal is an absolute realism in which the portrayal is indistinguishable from the world in which we live and move and have our being. The Christian Right got into the act in 2006 by pushing the Left Behind franchise into the video game market. Critics ridiculed the attempt, not so much because the narrative is silly and misogynistic but because the portrayal isn’t very realistic (to put it another way, mainstream gamers complained because it wasn’t literal enough). However, at roughly the same time as the release of the Left Behind game, Santa Monica Studio released God Of War which among other things allows gamers to rub shoulders with Titans. You know the Titans, don’t you? They’re the children of Gaia and Uranus from Greek mythology, presented here as giant 3D beasts, as real-looking as the coffee cup on your kitchen table. After meeting Titans, if you can’t see the imaginative trick you’ve been co-opted to participate in, this blog may not be a good fit for you. Go check out Perez Hilton instead.

Film isn’t at its most literal when it aspires to realism; we reserve that honour for its attempts to adapt novels to the screen. Think of all the films you’ve seen that are prefaced by the words “based on a novel by …” or “inspired by …” or “based on a true story”. To establish that the novel-adaptation approach to film-making is not some peripheral habit, consider the Mid-Continent Public Library’s database which lists 1450 novels and stories that have been turned into films. If Marshall McLuhan is correct in saying that the medium is the message, then what message should we take from the kind of medium reapproapriation that the film industry loves to inflict on the written word? Sometimes, I wonder if filmmakers aren’t saying: okay, so you read the book; now we’re going to show you what really happened. The problem of realism in film is that it often presupposes (and entrenches the view of) a univalent literal text, running roughshod over ambiguity and competing (often irreconcilable) interpretations. Take, for example, Herman Melville’s novel, Moby Dick which was adapted for the screen by Ray Bradbury, directed by John Huston, and starred Gregory Peck as Captain Ahab (for some reason this entry is missing from the Mid-Continent Public Library’s database). There is an ongoing debate which, to my knowledge, has never been resolved, about the “whiteness of the whale.” Does it stand for a spiritual principle? If so, then what? Or does it stand for America? Melville never left behind a definitive statement, so we can’t be certain what he intended. However, the one thing that critics can agree on, is that the novel is an allegorical tale. i.e. the thing presented stands for something else. By definition, it cannot be understood as a literal tale. A film that represents the reality of a raging sea captain obsessed with avenging himself against a whale that ate his leg is difficult to understand as a commentary on competing cosmic forces because it brings concerns like plot and setting and characterization and action to the fore. Huston’s Moby Dick is a great film, but that’s because it’s a great film, not because it’s a great visual interpretation of a novel.

As an afterthought, I can’t help but wonder if the rise of commercial realism in publishing doesn’t have something to do with the increasing interplay of film and novels. Writers raised on a ration of TV and Hollywood films intuitively conceive of their writing as adaptations from film (as if the movie version has already played in their head before they sat down to their keyboard).

Science/Economics:

Both the disciplines of western science and economics are grounded in rationalist epistemologies. Scientists and economists observe phenomena and try to explain them. That’s it.

If nature (in the case of science) and collective human conduct (in the case of economics) are the texts, then classical accounts of science and economics hold that those texts are reducible to univalent definitive interpretations. If you want to know why something is the way it is, science can tell you, maybe not today, but someday. It applies a methodology (let’s call it epistemology-in-action) of observation, theorizing and experimentation, that develops progressively refined explanations. Science stops applying its methodology only when the explanation is refined enough to count as an answer. Ditto for economics.

The account I’ve just given of science and economics is another way of saying that they are forms of literalism. Both disciplines assume of the world that one can move beyond interpretation to the thing itself. There are a couple critiques of this view that are worth considering. The first is well-known: the act of observation changes the thing observed. The very fact of our (self-aware) presence in the universe thrusts it (i.e. the universe) into an indeterminate state in which univalence is impossible. The second is a stronger version of the first and provides a segue into the point of this whole reflection of mine: science and economics have nothing to do with epistemology; nobody cares about phenomena as abstractions (knowledge for the sake of knowing); phenomena count only when viewed in instrumental terms (knowledge for the sake of political advantage). Science isn’t a passive act of observation but an instrumental endeavor to manipulate the world (build bombs, refine oil, dam rivers). Economics isn’t a quiet catalogue of human transactions but a pragmatic tool to push activity in desired directions (stimulate market economies, promote capitalism, set policy objectives).

Explanation and Power:

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with manifestations of literalism. In fact, literalism suggests a poignant yearning. It reflects the idealism that prompted Martin Luther King Jr. to speak of people—all people—as brothers and sisters. It reflects the longing for perfect unmediated connectedness between all peoples, and between all peoples and the natural world. Literalism is the impulse that seeks the reconciliation of a fallen humanity and a remote God. Literalism is the cord that ties the mundane to the transcendent.

At the heart of the Christian narrative is a literalist gnome ushering us from the Genesis accounts of human alienation (driven from the garden of Eden, the tower of Babel, the Flood) to a disobedient Israel thrust into the diaspora, then onward to a promise of redemption, to Pentecost (Babel’s mirror image), to a reintegration of humankind and God at the end of history. The narrative is literally true. That is: the narrative yearns for a perfect self-effacement of human consciousness.

As noble as the aspiration, the problem with literalism is that, like our science, instead of enjoying it for its own sake, we treat it instrumentally. Rather than as a kind of knowing, we use it to manipulate other people and the wider world. Instrumental literalism engages us in the act of explanation. Explanation assumes a privileged explainer and an ignorant listener. Explanation is an assertion of power. It is a rejection of difference in the attempt to force our listeners to see the world as we see it.

There is a paradox at the heart of this post: by writing in an explanatory mode, I risk imposing my narrow univalent views on my readers. I may aspire to something wider, of course, but am unable to help myself. Personal anxieties, the need for control, a desire to feel right, all these push me away from a more relaxed way of knowing. Are there any workarounds that help me escape this paradox?

I believe so, and I believe they all begin with an outright rejection of literalism, not because literalism is a bad thing, but because literalism is an impossible thing. It is the expression of yearning for an ideal state, in the same way that Christmas cards often are an expression for peace on earth. Peace on earth is a fine ideal, but it’s impossible, not because humans are incapable of peaceful co-existence, but because, when delivered as a Christmas card yearning, it expresses a desire to achieve a final state for all time. Humans can’t exist in a final state for all time; we are not wax figures at Madame Tussaud’s. We are dynamic beings embedded in dynamic ecosystems as part of a d/evolutionary process. Our expressions are responses to that dynamism.

If I am to offer workarounds to the colonizing force of explanation, I must accommodate such dynamism by remaining open-ended. Here are some suggestions:

1. Free play

Here, play doesn’t refer to games with objects and rules, but to the free play of children. There’s no reason why grownups can’t do the same thing when they share ideas. Play promotes creative engagement.

2. Aesthetic sensibility

Here, aesthetic sensibility doesn’t refer to the critic’s evaluative blender or the advertiser’s airbrushed zit remover (it’s neither intellectual nor commercial), but to a drawing up in fits of wonder. Here, aesthetic sensibility is the cultivation of the feeling you get when you see a full moon in a clear sky or hear a cathedral organ rumble the foundations or hold a newborn for the first time.

3. Conversation

Here, conversation doesn’t refer to debate or persuasion, but to the lifelong give-and-take between friends which places the person before the content.

4. Confusion

We feel anxiety when we fail to understand something. We feel a similar anxiety when we encounter multivalence and indeterminacy. We want our world to be comprehensible and reducible to fixed concepts. Since, as the Rolling Stones have observed, we can’t always get what we want, it may prove more practical to cultivate a comfort with confusion. We can answer our anxiety by learning to live with complexity that never resolves itself to simple buzz words and by treating with suspicion any blog post that draws its discussion to a neat close.

[1] We treat dead artists in precisely the same way, assuming that their works are the exact expressions of their aesthetic intentions. Literary critics explain away apparent inconsistencies in Shakespeare by pointing to underlying rhyzomatic coherencies in order to produce a unified self-consistent oeuvre while absolutely shunning the possibility that Shakespeare could have had off days, could have written passages while drunk, been preoccupied with his latest diagnosis of syphilis, etc. because, well, because The Complete Works of William Shakespeare is canonical.

[2] See fn 25 of “Big Red Son” in Consider The Lobster