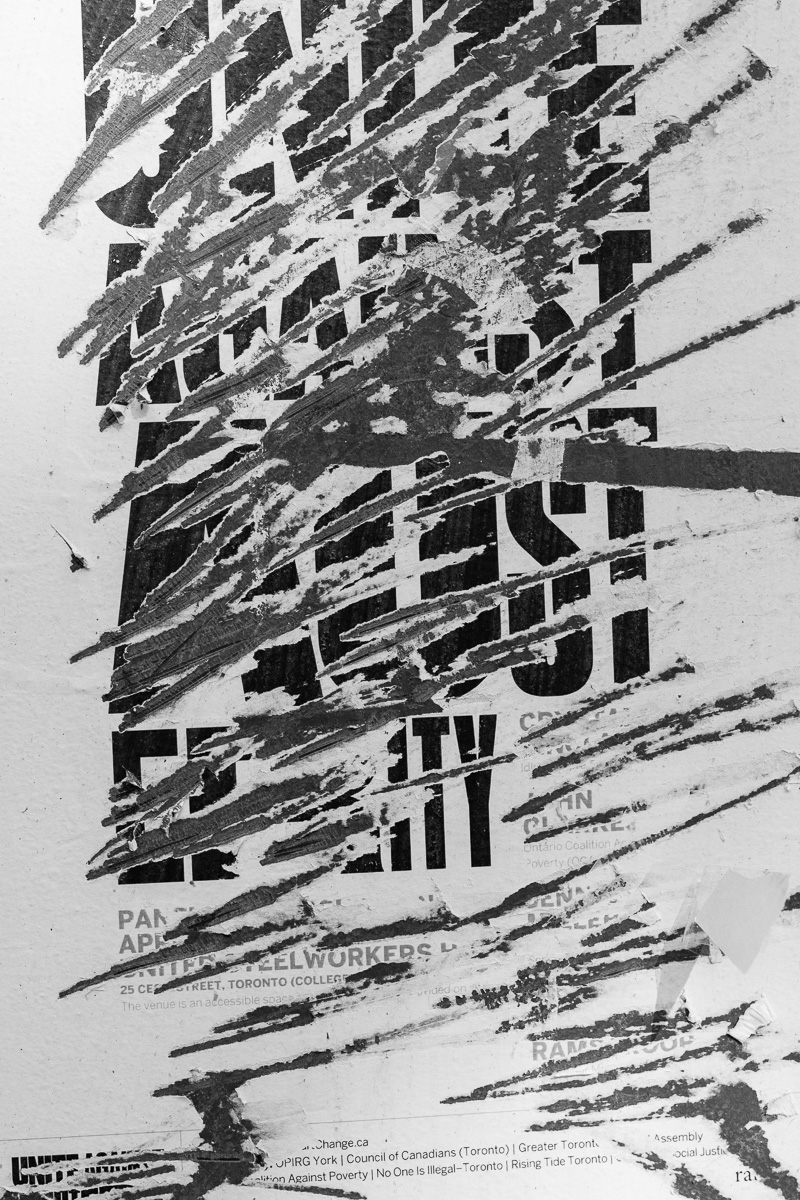

I recently bought a used copy of a photo book, Nowhere In Particular, by a medical doctor/TV and theatre director/photographer named Jonathan Miller. It features photos of rooftops, corrugated sheet metal, bits of canvas, and (mostly) palimpsests of weathered posters and torn advertising. All the images are closely cropped (or presented as a series of progressive croppings) that make it impossible to discern anything about their context and (perhaps) their meaning. The images are accompanied by a fair amount of text. When I bought the book, I assumed the text would provide the otherwise missing context. At the very least, I expected the text to explain the author’s methods or motives. Given the title of the book, I assumed that he was engaged in a project similar to Pico Iyer’s The Global Soul which meditates upon the nowhereness of intentionally global spaces like hotels, airports, and chain restaurants. Closely cropped photos might reflect a similar sensibility.

If the accompanying text bears any relation to the photos, it’s a mysterious relation. One snippet is a quotation from Mansfield Park; another, a discussion of madness from Proust. Some are personal reflections on arcane concerns, like the question why chapter summaries in 19th century novels are written in the present tense while the chapters themselves are written in the past tense. The only discernible connection between the photographs and accompanying text is that they reveal the tastes and interests of a single mind, Johnathan Miller’s. There’s something unsettling about a book whose method appears to be disruption and incongruity. The fact that it appears as a book, with its plastic sheen and crisp corners, lends the enterprise a unity and authority it might not otherwise warrant. It’s a deception or, more likely, a game.

Maybe the point of the game is to demonstrate that, when faced with a collection of incongruities, we can’t help but find relationships amongst the disparate parts, investing them with meaning. The discernment of meaning in chaos is a comfort in the same way that god is a comfort to the religious and Darwin is a comfort to the irreligious. Our spirits find solace in the conviction that at the heart of the universe is an unfathomable singularity and that at the heart of that unfathomable singularity is an indivisible kernel of reason. Then again, if the point of the game is that any point is possible, then one can’t very well privilege that point. It’s just as plausible that the point of the game is to demonstrate that what Ponce de Leon was really looking for in Florida was the recipe for Coca Cola, or that, since the deregulation of the bird market, inflationary pressures have made a bird in the hand worth three in the bush. Or maybe seeking a point is beside the point.

Maybe it would be more fruitful to ask why a book of incongruities makes me feel uncomfortable. I like my text to bear some relation to the photographs it captions. This is a reasonable thing for text to do. Text and context. That way, I know what I’m looking at. While Miller shot in film, digital photography has taken things a step further by embedding text (in the form of keywords) in the exif file. And if you post photographs online, you tag them so search engines can properly index them. If your photo of an upper east side mud wrestling competition is tagged #landscape #rural #farm #cow #holstein #patty, the farmer searching for images to decorate his marketing brochure is going to be sorely disappointed. I don’t write this to be flippant, but to illustrate one of the ways in which digital best practices contribute to visual literalism i.e. the belief that the subject of a photograph must bear a one-for-one correspondence to an object in the real world which allows the object to be readily described with a series of specially marked nouns and gerunds e.g. #cow #shitting.

Current photo technology furthers our susceptibility to visual literalism by practically guaranteeing that every shot makes the correspondence between subject and object obvious. Reinforced by literalism in other areas of endeavor—the polarizing effect of social media, the loss of nuance in public discourse, a widespread refusal to engage, or even acknowledge, difference—, what began as a simple observation about the current state of photography has been elevated to an aesthetic which enjoys not merely legitimacy but the force of moral necessity. The failure to make obvious sense is an affront to the sensibilities of decent right-thinking people.

Writing about the contemporary literary novel, the critic, James Wood, calls this aesthetic “commercial realism.” A confluence of trends has produced this aesthetic: the publishing house as subsidiary of the transnational media corporation, the global hegemony of the house style, the digitization and universal dissemination of text, the global ascendancy of rights-based copyright regimes, etc. Commercial realism has such a hold on our collective imagination and on our expectations about what counts as an aesthetic that we can hardly remember what preceded it. We forget that it’s a contingent blip on a wide arc whose trajectory is marked by a long series of other contingent blips.

What I have described as visual literalism could just as easily be called commercial realism, and for many of the same reasons that invite the term’s application to current literary practices. The same transnational media corporations manage our “visual ecology.” The global hegemony of the house style finds its correlate in the requirements of stock photography pools, modeling agencies, photo competitions, and the EULAs of large photo-sharing web sites. And digitization treats text and images indiscriminately, as do rights-based copyright regimes.

Visual literalism denigrates the metaphor. I use metaphor in its most general sense to indicate the radical leap between disparate thoughts. It’s the patterns of light and dark through a venetian blind that inspire a poem. It’s the image of a snake biting its own tail that prompts a scientific breakthrough. It’s epiphanic. It’s associative. It’s aleatory. It’s a jazz of the eyes.