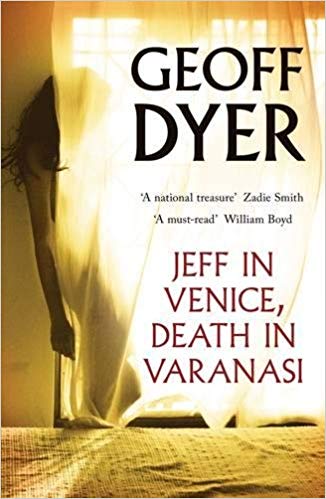

The 7th installment of my January Book Project is Geoff Dyer’s 2009 novel, Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi. See my earlier review of his 2011 non-fiction collection, Otherwise Known as the Human Condition. Maybe I should have read these in the order of their publication. And yet it seems fortuitous to have done things in reverse because Otherwise etc. alerted me to many of Dyer’s concerns/interests/passions and I came to his novel ready to watch how they played out in a fictional space.

As the comma in the title suggests, Jeff etc. has two halves with a break in the middle. Maybe it should have been a period instead of a comma because the break is so strong that it almost feels like two novellas rather than a single novel. In the Jeff in Venice half of the book, we meet Jeffrey Atman, a freelance journalist who is commissioned to conduct an interview at the Venice arts festival, La Biennale. Jeff’s final act before departure is an £80 visit to a hair dresser to dye out the grey so he doesn’t look so middle-aged. When he arrives, Venice is hot. There are lots of parties, lots of Bellinis, lots of schmoozing with pretentious art snots. And then. And then. And then he sees Laura, tall, beautiful, shoulder length dark hair, barely his side of thirty. They click. He wants to see her again but she refuses to reveal the name of her hotel. She thinks it would be romantic if they left their meetings to chance. Jeff wanders through the streets of Venice, angst-ridden, catching glimpses of Laura as he cruises by on a vaporetto, but unable to act. At last, they meet. Erotic cocaine-enhanced encounters follow. La Biennale ends and Laura returns to her home in LA, leaving the future to chance.

The Jeff in Venice half offers a vaguely comical look at the buffoonish sexuality of straight middle-aged men. This should be a sub-genre of the erotic novel. Certainly it’s well-known in CanLit with the novels of Brian Fawcett, David Gilmour, and the grand-daddy of them all, Mordecai Richler. Jeff Atman is sincere in his desire for authentic connection, but something about the environment conspires against him. It’s as if the art world gives him one big Botox smile and all the sincerity evaporates. In one of their last encounters, Jeff and Laura cruise across the lagoon to San Michele where they visit the graves of Igor Stravinsky and Ezra Pound. Where else but a cemetery can one go after all those parties and cocktails and hotel shags.

The Death in Varanasi half of the novel presents a disconcerting break. It’s separate from the previous narrative, both in time and space. But it’s more disconcerting because we expect a continuation of the encounter between Jeff and Laura. After all, Laura plans to travel and Varanasi is one of her destinations. But we never meet Laura again. The second half opens with: “The thing about destiny is that it can so nearly not happen and, even when it does, rarely looks like what it is.” We want Laura, but she’s not there. What then is the destiny that almost doesn’t happen? The second half of the novel is also disconcerting because the narrative voice changes. The first half was told in the third person. The second half is told in the first, and while we have no reason to believe that our narrator isn’t the Jeffrey Atman of the first half, there’s no reason to suppose it isn’t someone else either.

Our narrator has been sent to Varanasi to write a travel piece. After the allotted time has expired, he decides to stay on, checking into a hotel that’s closer to the Ganges River and to the heart of the city. Whenever he goes out, the beggars swarm him. Everyone wants to get their hands on his tourist rupees. But slowly that changes as he is drawn into the life of the city and begins to look less like a tourist and more like a local, wandering around in a dhoti, growing a scraggly beard, adapting to the various bugs in the food and drinking water. There is a sly allusion to The Ambassadors, by Henry James. James tells the story of Strether, who goes to Paris to rescue his finacée’s son from a life of alleged dissolution only to find himself transformed from an American outsider to a man at ease in a foreign world. Jeff (the failure to name him seems deliberate and deliberately fitting) undergoes a similar transformation.

The Varanasi half of the novel is littered with images of death. The first thing he sees is the pyre by the Manikarnika Ghat where bodies are publicly cremated. He watches the fat and skin burn from a corpse and when it is burned, the attendant cracks open the charred skull to release the soul. He sees a dead cat floating in the river. Two dogs chew at the arms of a body. Death is all around him. And yet there is an ironic inversion that happens here. Where the Jeff of La Biennales chases after life in a sex- and drug-fueled rocket that lands in a place of death, the man in death-strewn Varanasi gradually settles into a place where desire fades and the possibility for a new kind of life appears. We see it in his shifting response to the local guru. At first, as far as Jeff is concerned, the old man spends his days uttering gibberish and taking money from gullible Western backpackers. Later, he pays the man a few rupees simply to sit in front of him and stare into his eyes. He discovers himself in the old man’s gaze. Later still, we witness Jeff talking to a German tourist fresh off the plane. We see Jeff through the tourist’s eyes. He has become the old man talking gibberish by the Ganges. But we knew right from the start that, with a name like Atman, something like this was going to happen. To our rational Western sensibilities, there is no apparent difference between enlightenment and gibberish.

In terms of depth and quality, Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi stands shoulder-to-shoulder with E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India.