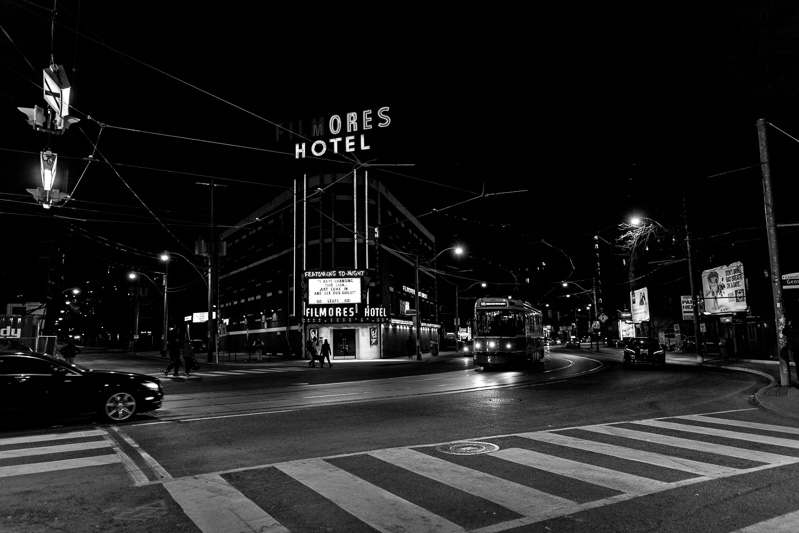

On my Instagram feed, local photographers have been posting images of Filmores Hotel which stands on the northeast corner of Dundas Street East and George Street. It’s something of a local landmark—maybe a landmark of sleaze—and likely to come down now that it’s been sold to Menkes Development. I decided to capture it one last time for posterity. Famed for its lap dances and its rooms rented by the hour, Filmores Hotel is a darker version of The Grand Hotel, its classier sister around the corner on Jarvis Street.

Adding to the local colour are the halfway houses on George Street. They help marginalized people, like mental health out-patients and parolees, transition into a more stable life. Several years ago, when I was shooting near the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) near Queen and Shaw, I had an animated conversation with a man who cautioned me against shooting on George Street. If I went in with a camera, then I’d likely leave without it. While I take no warning as an absolute rule, my instincts tell me his warning has something to it. Always, I enter that neighbourhood with my hackles raised.

My aim was to reach Filmores Hotel in the crepuscular light. I’ve previously shot it at night using a monopod, and I thought it might be nice to capture it in an intermediate light. The idea was to wander all afternoon and time the end of my wandering to arrive in the early evening. As the sun set, I stood on the southwest corner of Dundas Street East and George Street, pulled out my 5DS with 50mm Sigma Art Lens, and began to shoot. I repositioned myself in front of the Smoke’s Poutinerie so I could get the overhead crosswalk sign in the foreground. As I continued to shoot, I heard a woman’s voice immediately to my right: Stop shooting! I ignored the voice and kept shooting. Stop taking photographs this instant. I lowered the camera and looked to my right. No more than two metres away stood a young black woman who wore gold rimmed glasses and a toque.

— Sorry, were you talking to me?

— Yes. You have to stop taking photographs.

— Why?

The woman seemed taken aback that I would ask such a blunt question.

— Why?

— Yes, why?

— Because. She stammered. You have no right. It violates the Canada Privacy Act.

With her North London accent, she pronounced the word privacy with a short “i” which, to be honest, sounds far more elegant than the way we locals pronounce it. For a fleeting moment, it felt as if I was having a conversation with Zadie Smith. The illusion evaporated when I remembered that Zadie Smith isn’t whack-a-doodle.

— I’m a lawyer and I assure you: you’re wrong.

— No I’m not.

— Yes you are.

— And you’re not a lawyer, either.

In point of fact, the woman was correct. I used to practise law, but when I stopped, I ceased to be a member of the Ontario bar. However, I wasn’t about to share that technicality.

— I am a lawyer, I said.

— You can’t be a lawyer.

— Why can’t I be a lawyer?

— Because if you were a lawyer, you wouldn’t be using a camera to violate the Canada Privacy Act.

Her logic was impeccable. I told her I wasn’t going anywhere. I may also have let it slip that I thought she was crazy, as in: You’re a bit of a loon, aren’t you?

She stomped inside the Smoke’s Poutinerie. I noted her branded apron and realized she worked behind the counter there. She yelled something muffled at me through the window. I couldn’t make it out, except the part about shoving something up my arse, maybe my camera, which I’m sure would not be good for it.

Well, I said to myself, I’ve done all the damage I can do here. I walked back to Jarvis and waited at the light. Nevertheless, I had a feeling. My hackles were up. I turned and there she was, leaning against one of the big glass panes of the new condo build on the corner. She held her arms folded and wore a glib smile.

— So you’re going to follow me, is that it?

She didn’t answer.

— You know, I didn’t take any photos of you.

I stepped towards her and she recoiled. I confess: I can get a bit Aspergery about my entitlements and my insistence that they be observed. I know damn well that I’m right but sometimes lack the common sense to pull back for the sake of prudence or, in this case, convenience. It’s like an evil monkey that whispers in my ear: Let’s see how far you can push this. Even so, there comes a moment when I can no longer treat an interaction as an algorithm but must account for what Graham Greene might call the human factor. It occurred to me this woman might be afraid of me. A middle-aged white man asserts his right to take photographs in a public place and makes it amply clear he won’t back down. A slight and younger black woman feels provoked and challenges him. What is the reality of this exchange? Do we frame it in terms of legalisms that treat the actors as ciphers? Or do we frame it in terms of a power dynamic in which race and gender have a role, and in a context subtly influenced by the alienating effects of urban hyper-development and social media?

I assumed a more conciliatory posture and made to introduce myself and to share with her a little of what I try to do when I wander through the city with a camera slung around my neck. Again, she recoiled. She followed an odd looping arc that returned her to her place leaning against the glass pane.

— Fine, I said.

I shrugged and returned to the intersection. When the light changed, I crossed Dundas and headed north up Jarvis. The woman was following me. I didn’t look back but somehow I knew the woman was following me. I was headed home. I wondered how long before she gave up. Or would she follow me all the way to my doorstep? I stopped and turned to face her.

— Doesn’t feel so good, does it? she said.

— What?

— Me. Violating your privacy the way you violated mine.

— You’re not violating my privacy.

— Yes I am.

— No you’re not.

— I’m making you uncomfortable.

— I’ll give you that, but you’re not violating my privacy. We’re standing on a sidewalk. It’s a public space. I have no reasonable expectation of privacy here.

— I’m a priest.

— A what?

— A priest. We can’t be photographed. It violates our religious freedom.

— What denomination?

— I’m an Orthodox Jew.

— You’re an Orthodox Jewish priest?

— Exactly.

I stared at the toque, the apron, the gold rimmed glasses, the absolute sincerity of her near-beatific expression.

— If you photograph me, you capture my unique identity, and that is theft.

— So what about that? I pointed to a surveillance camera suspended over the Dundas/Jarvis intersection.

— That’s different.

— How is that different?

— That’s on Dundas.

— But I was standing on Dundas when I was shooting Filmores.

— That’s for preventing crime. But you. I have no idea what you mean to do with your photos.

It took some time, but I accomplished what some street photographers describe as de-escalation. I had taken 20 exposures of Filmores Hotel. We stood together on the sidewalk and examined each exposure, and I persuaded her of what I already knew: she did not appear in any of my photographs. However, I failed to unseat her belief that because I walk with a camera I must necessarily violate privacy wherever I go. Then again, I didn’t try. She seemed quite fixed in her convictions, as no doubt a priest must be.