In Memory of Memory, Maria Stepanova, trans. Sasha Dugdale (Toronto: Book*hug Press, 2021)

It had taken me only a few pages of In Memory of Memory to decide that this is one of the best books I’ve read in quite some time. I’m not the only one of this opinion. Half way through the book, I received an email from its publisher advising that it had been shortlisted for the International Booker Prize, winner to be announced on June 6th. As I see it, the only impediment to winning is that some jurors might question whether it qualifies as a novel. It has about it a whiff of categorical ambiguity as readers are left uncertain what shelf to put it on when they’re done with it.

The book proceeds like an extended piece of creative non-fiction. Maybe memoir. Maria Stepanova is descended from a family of Russian Jews and is determined to learn something of her family history. Like a good researcher, she starts with primary sources like letters, photographs, and official documents. She visits towns where relations once lived and, where possible, examines local archives and municipal records, knocks on doors, tramps through overgrown cemeteries. However, when she engages her own process honestly, she discovers that her family story is not a history she uncovers, like the artifacts of an archaeological dig, so much as a story she constructs. Even in matters she remembers directly, there is a sense in which the facts fade from view and she is left only with impressions. A reader who is after a “scientific” historical account might say that Stepanova allows her subjectivity to inject distortions into her investigations. But Stepanova is more relaxed about matters, suggesting that the fallibility of memory does not arise from a failure of objectivity so much as from the same processes that lie at the heart of our creative impulses.

No, that’s not it. More like memory inhabits us. At one point, Stepanova embarks on a riff about postmemory, an idea first articulated by Marianne Hirsch. In an ensuing handful of pages, she mentions Homer, Primo Levi, Hannah Arendt, and Susan Sontag. And this is supposed to be a novel! Hirsch introduced the idea of postmemory to address the problem implicit in the call to remembrance by Holocaust survivors. What happens when the last of the survivors dies? How can the children of Holocaust survivors—or anyone for that matter—remember what they have not themselves experienced? I don’t pretend to understand the notion of postmemory, so forgive my crude description, but I take it to be an answer to this problem. The trauma of a generation transcends the simple evidentiary lines we traditionally ascribe to memory and inhabits the consciousness, the spirit, maybe the very being, of succeeding generations.

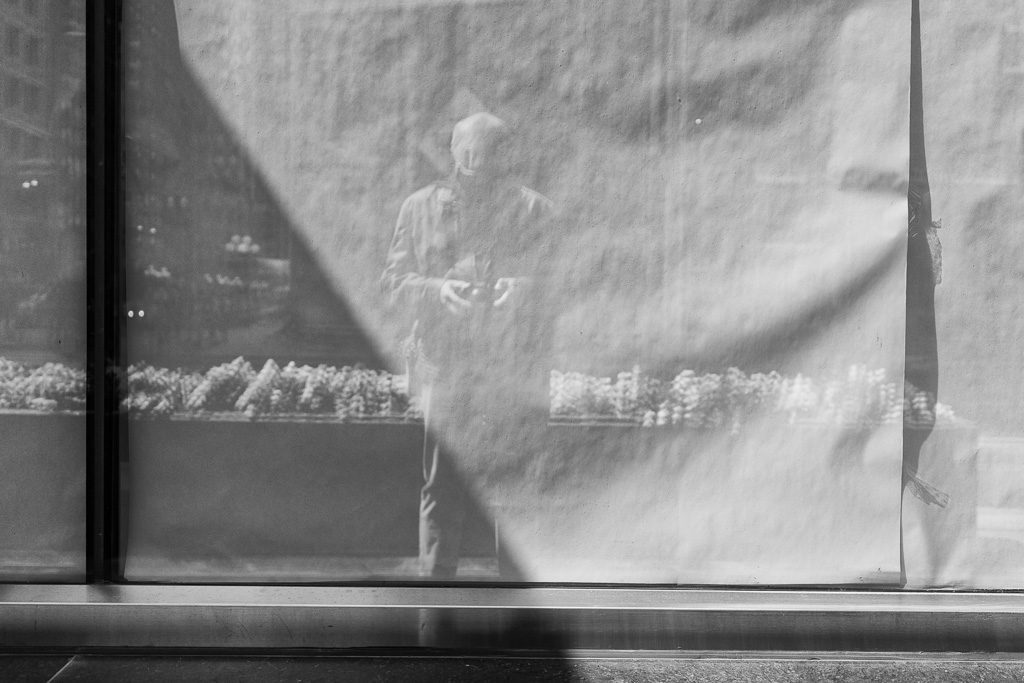

When she arrives at Sontag, it is in reference to the way Sontag reads photographs. Naturally, as a photographer, I am particularly intrigued by Stepanova’s examination of old family photographs and commend these passages to photographers—especially documentary photographers—who concern themselves with questions about the evidentiary value of photographs. For those of us concerned with close “readings” of photographs, we typically follow the example of people like John Berger, Roland Barthes, and Geoff Dyer. But Stepanova takes a different tack, acknowledging a certain unknowability at the heart of every image, and opening herself up, instead, to be inhabited by the photograph. In a way, the photograph reads her, and not the other way around.

But that’s not it, either. The thing about Stepanova’s personal history is that it doesn’t involve a Hollywood-movie-worthy account of harrowing survival. Yes, there was an uncle killed as a young man in the siege of Leningrad. And, yes, she had grandparents who went hungry. However, they didn’t suffer these traumas because they were Jews but because they were at war. Yes, had they lived in Poland or Germany or France, their story would have been radically different. It adds a twist to Hirsch’s notion of postmemory. What weight do we give to the remembrances of ordinary people who suffer no extraordinary traumas and whose legacy does not pass to the succeeding generation by a gossamer thread that could have snapped at any moment?

Again and again, Stepanova celebrates the commonplace, whether she finds it in the stories of the people she remembers, people who never make it into history books or bear honorific titles or even professional designations, or in the objects she examines which are never the pristine articles that find their way to glass cases in museums but are the worn out items of daily usage. To a certain extent, we all rely on acts of remembrance—sifting through old letters and photo albums, sharing stories with our cousins, visiting childhood haunts—to buttress our sense of personal identity. But few of us can draw upon harrowing tales and larger-than-life personalities. For the most part, the raw materials we bring to the task of constructing a sense of self are modest at best. Stepanova takes our hand, one ordinary soul walking with another, and demonstrates how we can work these raw materials to craft something luminous.

Although originally published in 2018 before there was any hint of pandemic in the air, the release of the translation was timed perfectly to deliver a message so fitted to the moment. As I drift my way through a third wave of Covid-19, subject to yet another stay-at-home order, I have been forced to reconcile myself to the bare-walled ordinariness of my existence. Never have I taken such sustenance from a writer so committed to setting aside pretensions and turning her attention to the humble, to the overlooked, in a word, to people like me.

Finally, a note about Maria Stepanova’s method. Or anti-method, since there’s nothing particularly methodical about her writing. Maybe I should call it her approach. Or style. She writes in an aleatory manner. Associative, like jazz. Sometimes following a tangent as one would expect of a curious, restless mind. Always interesting. Inclined to draw fascinating associations between seemingly disparate thoughts. Her writing reminds me of Olivia Laing or Geoff Dyer. After a year during which most of us were exposed to one of the drabbest most pedestrian ugly minds on the planet, In Memory of Memory arrives as a gust of fresh air, offering us the companionship of a decent and empathic heart. Read it the way you’d take your vaccine, as an antidote to the worst of 2020.