Someday I would like to write a dissertation. I would use big words and quote great minds and when I was done I would tell people that I had made a definitive statement: a philosophy of the banal. I would write it in the spirit of Albert Camus who offered the world a philosophy of the absurd. Only I would do Camus one better. Camus’ famous essay, which opens The Myth of Sisyphus, is a deep reading of the early 20th century—the rise of nationalism, Fascism, totalitarian regimes, a war that engulfed all of Europe and spread like a cancer even to his home in North Africa.

Those victims of the 20th century who survived needed men like Camus to describe what they had experienced. But the victors saw no need for outsiders to hold up a mirror to them; like blind painters, they would describe themselves to themselves. The most spectacularly victorious of the victors—America, Britain, Canada, Australia—framed their success in terms of freedom and democracy which they exercised through advertising and consumption. The victors replayed the spectacle again and again—in Korea, Viet Nam, the Falklands, Kuwait, Iraq, Afghanistan—but the cry “We fight for our freedom!” rang hollow because the victors had no attachment to those places.

Life for the victors is dominated by the values of a bloated middle class for whom Camus’ absurdist philosophy holds no meaning. We have “freedom” to give us meaning. To suggest an absence of meaning, as Camus did, is itself absurd. And yet the longer we live in this suburban peace of ours, the more we come to recognize the limit of our franchise: the glorious right to purchase kitschy consumer goods that break the day after the warranty expires. We show off the bright shiny things we’ve bought, smile at our neighbours through plastic Botox™ lips, then declare ourselves happy because we have everything the ads tell us we ever wanted.

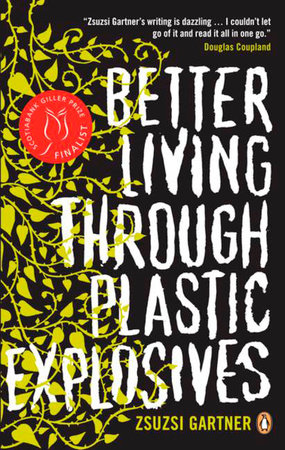

We, the victors, have embraced the banal, not simply as a description, but as a philosophy. Even as Camus wrote of absurdity as a philosophical precept, he recognized that it deserved its own literature, and so he gave it a literary push with his own pen. In my own humble way I have endeavored to do something similar, giving banality its due here on my blog. It has been a lonely endeavor, but I have discovered a kindred spirit in Zsuzsi Gartner and her collection of short stories, Better Living Through Plastic Explosives.

Zsuzsi Gartner is from Vancouver. That fact is important, not only because many of her stories are set in and around Vancouver, but also because Vancouver has come out to the whole world as a Mecca of banality. While ordinary people in Egypt take to the streets and topple a dictator, and women in Saudi Arabia risk prison for the simple act of driving a car, Canadian youth riot in the streets of Vancouver because men who are paid millions of dollars to whack a piece of hardened rubber across a sheet of ice fail to perform as expected. This is the Vancouver Gartner documents.

Two points of clarification when writing of suburban banality in reference to Gartner’s work:

1) To say that Gartner writes about suburban banality is not to suggest Gartner is a banal writer. On the contrary, her writing is intelligent, playful, and filled with wit. When a woman plucking grey hairs swept them into the toilet and flushed, they “swirled into a small, furious animal before disappearing with a gurgle.” Meanwhile, her lover “smelled hairless, like a peeled cantaloupe.” In another story, a young filmmaker aspired to create a “moving picture so sublime the intended viewer’s heart would fold in on itself in an origami of joy.” Only a really good writer can create the space for readers to encounter and savour such gems. Gartner is like a literary Pez™ dispenser, popping the bricks out in rapid succession and loading a fresh pack of the sugared nuggets with each new story.

2) A related clarification: potentially banal pop culture references (like my Pez™ dispenser comment above) do not necessarily constitute a piece of writing as an artifact of banal pop culture. We don’t say “Parker’s Back” is a Catholic story just because Flannery O’Connor deployed Catholic imagery any more than we say that Kelly Link eats brains for breakfast because some of her stories feature zombies. My syllogism may be a bit off, but you see my point. Gartner laces her stories with a healthy sprinkling of banality, but that does not make her stories banal.

I am reminded of the old koan: how do you write critically about a banned work without getting yourself banned? The same problem applies here, mutatis mutandi. In fact, the same problem plagues any writer who tries to walk that narrow ledge with their backs to the wall of “high” culture and their toes wiggling over the chasm of “low” culture. Critics love to give such writers a shove and shout gleeful platitudes as they fall.

But I am inclined to think that, for writers living amongst the victors, there is no other ledge to walk. Those who write serious works of suffering and redemption, or suffering and tragedy, or even suffering and absurdity, come off as fraudulent. Suffering succotash, such writing is so far removed from the life of most North Americans that we can hardly read it without asking first if the author has done a good job of branding himself.

Banality IS our suffering. It is our harrowing trial, our bed of nails, our vision quest. As a culture, we have not yet worked out how the spiritual poverty of middle-class surfeit will deliver us to some new reality, some redeeming wisdom, or maybe a fall to rival Milton’s. But some, like Gartner, are mapping the terrain of what may prove to be a discrete genre—call it suburban banality—by declaring its conventions.

Here are a few of those conventions as revealed in Better Living Through Plastic Explosives:

1) Cul-de-sacs

Nothing screams suburbia quite like a cul-de-sac. In case you weren’t aware of its etymology, cul-de-sac is Quebecois for “dead end”. However, its symbolic value is trite, almost cliché (another Quebecoisism meaning “tired” e.g. voulez vous cliché avec moi ce soir). More importantly, the physical shape of a cul-de-sac throws neighbours into claustrophobic proximity. While most suburban settings, especially those involving thoroughfares, afford their inhabitants a fair degree of anonymity, the cul-de-sac does not. It is a useful literary device for forcing characters to reveal themselves to one another in ways they wouldn’t otherwise consider even with their therapist.

2) Supernatural Beings

Often this takes the form of an alien invasion. This is the expectation generated by the title of the story “We Come In Peace”, but Gartner surprises by resorting to mass angelic possession instead—kind of a religious Midwich Cuckoos. Five teens (who live on a cul-de-sac of course) wake up one morning to find themselves possessed by the spirits Zachriel, Elyon, Barman, Yabbashael and Rachmiel. The angels have trouble adjusting to life as suburban teenagers. Being good just doesn’t cut it. One gets sucked into online gaming. Another gets pregnant. Everything goes downhill from there when the teen angels join forces with three wise men (homeless men who live in Hastings Creek) to race shopping carts down Mountain Highway.

Gartner provides a variation on this theme with “The Adopted Chinese Daughters’ Rebellion” when all the sanctimonious residents of yet another cul-de-sac adopt Chinese girls whose papers are stamped with the ominous “resident alien” label. As culturally sensitive white professionals, they try to raise the Chinese girls in their indigenous traditions (complete with the one family/one child rule). The Chinese girls pretty much go the way of the angels and turn into a bunch of bad-asses.

3) Political Correctness

We’ve already had a taste of this with “The Adopted Chinese Daughters’ Rebellion” which itself is reminiscent of the South Park episode in which Kyle’s parents move to San Francisco to live with more cultured people who sniff one another’s farts and drive new hybrid cars like the Pious.

Gartner takes PC-skewering to fresh heights with “Mr. Kakami”. Sydney Gross is a Vancouver film producer who tells the story of his star filmmaker, Patrick Kakami, gone AWOL. To secure a location permit on native land—on an island of old-growth forest off the coast of B.C., Syd and the crew had to attend a sweat lodge to demonstrate their spiritual integrity. After their sweaty ordeal, the lead actress climbs an old tree with a load of energy bars and Red Bull and refuses to come down as a protest against globalization. Syd has a vision, which isn’t supposed to happen to crass people like him. And Kakami disappears into the forest. When Syd hunts him down in a cave, the two sit like a pair of Platonic philosophers watching firelight flicker on the cave wall and sharing a conversation about the meaning of life. Kakami confesses that he sees things now. And what are these wise things he sees?

Scenes from Indonesian shadow plays, O. Selznick’s burning of Atlanta, the telephone call from Paris, Texas, Walt’s hippos in tutus, Lillian Gish in silent anguish, Harry and Sally in a clinch are reflected on the cave walls. A never-ending story.

4) Virility (or lack thereof)

Men fear for the loss of their virility. This is understandable. Suburbia was built on the backs of men who fought for our freedom. They were real men. They bequeathed their paradise to their children and grandchildren, but there was nothing we inheritors could do to deserve their bequest, no sacrifice great enough, no lawnmower powerful enough. Inevitably we who have grown fat on our unmerited peace must earn it, as Gartner makes clear in “Summer of the Flesh Eater”. A stranger moves into town—or cul-de-sac as the case may be. He is manly. He threatens to take the wives and impregnate them with the raw seed of his animal virility. Naturally the men must kill him, and not for any moral imperative. They are driven by something more fundamental than that—this is a Darwinian struggle—and the suburban intellectuals shall survive! Or at least prevent an impending devolution into the kind of primitive man who cooks meat on a barbeque.

5) Strange “Natural” Events

A Japanese cultural exchange student rides out of the forest on the back of a giant tortoise. Houses drop at random into house-sized sinkholes, but only when all the occupants are out. I have a theory about such things. We can’t read them as signs in a book and expect any more meaning than our ancestors divined from thunder storms and goat entrails. Stories that help the reader make sense of loss; the quest for closure; even Camus’ solemn declaration of absurdity. All these are misdirections that try to protect us from the fact that human beings have an almost infinite capacity to reduce even our most spiritual claims to a monstrous drivel. In the case of the sinkholes, their grand meaning distills to this: a Hummer-driving real estate agent is going to lose her commission because a $7.5 million house has disappeared. That’s it! As for the giant tortoise …

6) Foreign Languages

Foreign languages are important. They help us identify the aliens. Often these are dead languages—a Latin scholar lives on the cul-de-sac. Sometimes these are real languages—how else will the Adopted Chinese Daughters know their culture unless they learn Cantonese and Mandarin? But foreign languages are their best when we make them up. And so, in “Once We Were Swedes”, we have the reminiscences of a journalism teacher who used to speak to her husband in IKEAese.

7) Terrorism

There must be terrorism. And why not! After all, terrorism is the second most banal notion ever inflicted on the Western psyche. The first, of course, is that shit-flavoured definition of freedom we imagine is threatened by the aliens banging at our suburban doors. “Better Living Through Plastic Explosives” presents us with a twelve-step group for terrorists. Lucy is a recovering terrorist who hosts a gardening radio show, but she struggles against relapse every time a kid in a muscle car squeals past her front lawn.

I would add an eighth convention—cannibalism (especially as practised by zombies). However, apart from a hint of it in the title of “Summer of the Flesh Eaters”, cannibalism doesn’t figure prominently here, and zombies not at all. Maybe in the next collection. In the meantime, go out and buy lots of stuff (especially this book).