From the age of twelve until I started university I took piano lessons from a man named Alan who loved to read and always had a book in hand when he rode the subway. I remember after one lesson, maybe in ’78 or ’79, when we were chatting about—who knows—life, the universe and everything—when Alan laughed and told me he was reading Death in Don Mills, by Hugh Garner. I had never heard of Hugh Garner. It turns out he belonged to that loose affiliation of hard-drinking writers who reported for the Toronto Star and wrote novels on the side. Others in this group included Morley Callaghan and, most notably, Ernest Hemingway. Their prose is spare and to the point. But Death in Don Mills? You’d understand the eye rolls if you knew anything about Don Mills.

Don Mills is a suburban community in central Toronto which takes its name from a village that sat on the Don River in the days before Toronto swallowed up all the lands extending north from Lake Ontario. Even today, signs proudly announce that Don Mills was the first planned community in North America: mixed density, curvy streets, lovely schools, even a golf course. Nothing ever happens here. It makes an improbable setting for a hard-boiled roman policier. But there you have it. Toronto’s finest get called to a fictitious apartment building that fronts Don Mills Road somewhere between Eglinton and Lawrence. There’s even a reporter named “Jocko,” clearly a tip of the hat to Jocko Thomas, crime reporter, “reporting for CFRB from police headquar-r-r-r-r-ters.”

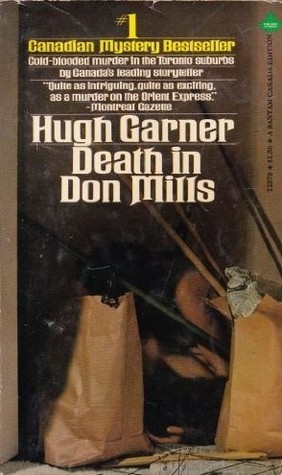

McGraw-Hill Ryerson published the book in 1975. Recently, I found a good first edition at a church book sale and spent an afternoon between its covers visiting a neighbourhood I had known as a kid. It’s an odd read. The book is almost an archeological artifact. It provides evidence of how much Toronto’s culture has changed, how much we’ve grown up.

You see, the man named Alan who introduced me to this book was gay. You can read more about him here. One of the suspects in Death in Don Mills is gay. I’m having difficulty reconciling Alan’s laughter to Garner’s portrayal of a gay youth struggling to survive in an early ’70’s Toronto suburb.

What strikes me as odd is that the portrayal purports to be sympathetic. The youth’s father is a die-hard homophobe who is filled with revulsion at the thought of his son. He serves as a foil to the investigating detective, Walter McDumont, who represents the voice of reason, the enlightened point of view, the unassuming liberalism of middle-class Toronto. And how does the voice of reason respond to the gay suspect?

By the end of the novel, it is obvious that the gay youth didn’t commit the crime. Nevertheless, the kid is in trouble. The detective could handle things in one of two ways. He could play by the book, arrest the kid and criminalize his behaviour. Or he could take the compassionate choice — treatment. Yup. McDumont is going to send the poor kid to the Clarke Institute (now CAMH).

“I’m not sending you to the Don Jail. I’ve been in touch with the Clarke Institute out near College and Spadina. I’m sending you there until the trial. I wouldn’t want to send you to the Don, where I’m sure they’d have to keep you isolated from the other prisoners for your own protection. In the Clarke you’ll be locked up but not in an individual cell. You’ll probably have access to any recreational facilities they have there and the use of a common room during the day. Whether they’ll put you in a dorm or a room I have no idea, but we’ll find out more about that when the doctor comes to get you later. His name’s Bob Macpherson, and he’s a Scotsman like me. I think from his voice over the phone that he’s a young guy. Now, I think they’ll go into your history much more thoroughly than I’m going to go into it here, and because they’re doctors whose job it is to bring people, some with your problem, many with other neuroses, back to what we think of as normalcy, you’ll probably have private therapy sessions and group therapy sessions. It will depend on you whether you accept the help they’ll offer you or not. That’s out of my jurisdiction. Anyhow, you’ll be much better cared for than you would be in the city jail. What do you think of it?”

“I think it’s super of you, Inspector. Thank you.”

I can still hear Alan’s laugh. Super! What was it about that laugh? Was there irony, caution, fear, a sly defensiveness? It couldn’t have been straight-up laughter at a silly pot-boiler about a murder in suburbia, could it?

The book illustrates how fluid is our notion of liberalism. A liberal point of view tends to understand itself by reference to the prevailing force of oppression. For gays, treatment was the liberal alternative when oppression meant criminalization. Now, we tend to think of treatment as a more subtle manipulation that nevertheless operates with as much oppression as criminalization. Liberalism has shifted its position to accommodate this new insight. And tomorrow? Presumably the desire to oppress can take hold on any ground. That makes the future face of liberalism impossible to predict.