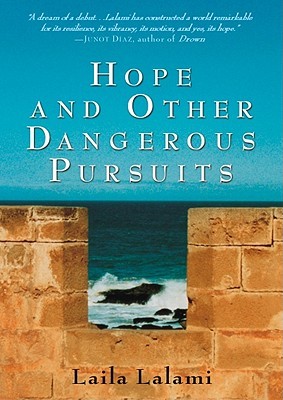

Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits, by Laila Lalami, Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2005.

This is the first novel of Laila Lalami and it created something of a splash when it was published two years ago. It is a little book, well–crafted and worth reading. Clearly Lalami has literary aspirations and clearly too she has the potential to write bigger pieces of fiction in the future. I hope the world can give her the space to do that.

My decision to post this review coincides with the arrival in my in–box of a hateful piece of tripe from the Ten Commandments Commission. It is material like this which gives me pause to worry that Lalami—and many other naturalized American Muslim men and women—may find the current state of the world too distracting to offer the best of themselves. The 10CC material is reductive to the point of inciting violence. It reduces the Muslim to a caricature—a servant of evil bent upon unleashing all sorts of terror upon the world. Then, when the Muslim is neatly confined to her box, the good Christian comes along and nails the coffin shut. How can people write when all around is the sound of hammers pounding?

So I offer this post for the following reasons:

1. to assure Muslims that most people who have assumed the name Christian reject such views as an evil of our faith which we must work to contain from within;

2. to assure Christians that most people who have assumed the name Muslim cannot be found in the 10CC description;

3. to present a decent piece of writing that deserves to be read solely on its merits without need for this religious crap as a preface.

On point one: reclaiming the name Christian from the fruit cakes is pretty much what this whole blog is about.

On point two: one of the great things about Lalami’s book is that through fiction it transports us into the world of contemporary Islam in Morocco. Human faces on human problems. While matters of faith inevitably crop up, at bottom these characters concern themselves not with ideology but with personal survival. They want what we all want—food, sex, connection, the chance for a future. Nobody has bombs strapped to himself. Nobody is screaming out fanatical slogans. And the pious in Islam are regarded with the same circumspection that I apply here to the 10CC people.

Now for point three, the story itself:

The story opens on a Zodiac somewhere in the Strait of Gibralter, transporting illegal immigrants to Spain under cover of night. The captain dumps the whole boatload some distance from shore and tells his passengers to swim the rest of the way. Inevitably, one drowns, the opportunist manages to make a break for it, but the rest are captured and deported. Then we shift to the backstory—a glimpse at the lives of four passengers and the motives which drive them to risk everything to start a new life in Spain. The second half of the novel follows the characters after they have been dumped from the zodiac, then concludes with a wonderful tale—almost a parable—that organizations like the 10CC ignore at their peril.

First we meet the “fanatic,” a teenaged girl named Faten, through the eyes of her friend’s father. She is a bad influence, her religiosity is tearing the man’s daughter away from him. Yet in the second half of the book we find a young woman whose desperation has driven her to prostitution. Then we find Halima whose regular beatings drive her to seek a divorce, but as she presents herself before the judge with bribe in hand, she suddenly changes her mind and decides instead to flee. Home again, shamed perhaps by her failed attempt to flee, she struggles to care for her children.

We also witness the lives of two young men. There is Aziz, the one who makes it to Spain, busing tables and managing to set a little aside as he works. We see him later, returning home to his wife, finding that things are different. Spain is not all that he had hoped for, but he can’t return to Morocco. At the same time, his wife has adopted more conservative ways. We are left to imagine how these tensions might unfold or unravel. Finally, we meet Murad, the English major, the one who, for all his education, can’t seem to match his more pragmatic siblings. As with everything else he tries, his flight fails, and so he finds himself working in an antique shop selling second–rate goods to American tourists.

In the novel’s final scene, Murad listens as two young American women shop for a gift. They seem interested in a particular carpet. They settle in for tea as they consider whether or not to make the purchase. Murad finally reveals that he understands English, sitting down at the table and offering them the story of Ghomari, the rug weaver.

Ghomari is a master rug weaver and in love with the beautiful Jenara. When the sultan learns of Jenara, he cannot abide that a rug weaver should have a more beautiful woman than him, so he kidnaps her and forces her into marriage. Ghomari weaves his sorrow into a tapestry that becomes renowned for its beauty. It is a portrait of Jenara holding a knife. Again, in jealousy, the sultan takes the tapestry. He puts Ghomari to death and hangs the tapestry upon the wall in his bedroom. One evening, Jenara appears with a knife. His vizir and other courtiers enter, but when the sultan calls out for their help, they see only a tapestry, for they can’t tell the artifice from the true person. When they leave, Jenara steps from before the tapestry and slits the sultan’s throat.

Yes, Lalami’s tale is artifice. But do not think for a minute that it is merely artifice. Standing before it is the Islam of the poor, the Islam of the oppressed, the Islam of the desperate. It is naive to suppose that such a state of affairs can continue; just as it is naive to suppose that a good writer can stick to the artifice without, in the end, offering a political voice.