Can queer theory be used as a tool to think about mental health? This is a question that has nagged me for a few years now, and in the fall, I had an opportunity to write about it for a course on liberation theology. I have been reluctant to post it, because, unlike most academic writing, I made this one deeply personal. I suppose I was afraid that if I shared my thinking too widely, it might feel a lot like walking naked through a shopping mall. However, I realize that, unless I make things personal, unless I’m willing to risk sharing from my own experience, then my writing loses two things. It loses a layer of credibility. And more importantly, it loses a layer of meaning.

In our liberation theology class, we were supposed to write reflection pieces based on the readings assigned for the week. The week devoted to queer theology included the following readings:

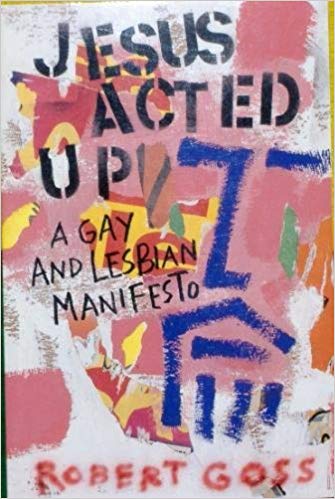

Goss, Robert, Jesus Acted Up: A Gay and Lesbian Manifesto, (New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1993).

Heyward, Carter, “Coming Out: Journey without Maps,” Christianity and Crisis, 11 June, 1979, 153-156.

Tinney, James, “The Third World, the ‘Third Sex,’ and the Third Way,” transcript of address to the first International Conference of Third World Lesbian/Gay Christians, 1982.

Schneider, Laurel C., “Homosexuality, Queer Theory, and Christian Theology” Religious Studies Review 26, no. 1 (January 2000) : 3-11.

What interests me is the question of identity. Should I try to “pass?” Or, at the other extreme, should I not simply come out, but come out as militantly different?—a bold assertion of lunacy?

Enjoy the piece. I hope it makes you feel uncomfortable.

I shall begin at the end of our readings with a phrase from Goss. He speaks of “the scandal of particularity.” He states that “[o]n Easter, God made Jesus queer in his solidarity with us. In other words, Jesus “came out of the closet” and became the “queer” Christ”. Is coming out a necessary step in identifying as queer? If so, then my investigation ends before it can begin. Certainly, Goss makes it explicit that coming out is necessary in order to do theologies of gay/lesbian liberation. But there does not appear to be a necessary connection between identifying as queer and doing a theology of gay/lesbian liberation. Perhaps, instead of a coming out, all that is needed to do queer theology is a declaration of difference, a public acknowledgment of one’s own scandalous particularity. The question then remains: does the declaration of difference have to relate to sexuality? If the differences which fuel a queer theology are restricted to matters of sexual identity, then a man who identifies as heterosexual may not be able to articulate anything liberative. But, given that queer theory aims to explode the givenness of categories, it seems plausible to queer the queer category by opening it up to issues which lie beyond sexuality. And so I shall proceed from my own scandalizing particularity.

Queer theology is contextual theology. All of this week’s authors work from within the experience of sexual expression beyond hetero–normativity. While Carter Heyward proposes an analytic method that avoids biography, nevertheless she makes it clear that she is a thirty–three year old graduate theology student, self–described variously as lesbian and bisexual (perhaps this ambiguity is deliberate). The title of the article by James S. Tinney makes it clear that he proceeds from biography: “Struggles of a Black Pentecostal.” Although the excerpts from Jesus Acted Up do not speak to the experience of Robert Goss, his writing is still rooted in the communal biography of the people for whom he speaks—with accounts of the early struggles against homophobic violence to the ravages of AIDS. I take my cue from these authors and offer my own story as a point of departure for considering what they present.

I am queer by analogy. My queerness is very much rooted in issues of identity, though not in issues of sexual identity (although I do not dismiss the possibility that sexuality is integral to my particular concern). For more than twenty years, I have struggled with a major mood disorder. This is my dirty secret. This is the scandal of my particularity. Like gays and lesbians, I can tell my coming out story. This is not the story of the day I first acknowledged publicly what had formerly seemed inconceivable—that I labour with mental illness; instead, it is the story of the day I first acknowledged publicly that my illness is untreatable—certainly untreatable from within the context of a medical hegemony which understands treatment primarily as therapy for acute concerns. On that day, I discovered that, although untreatable, I could still find relief. On that day, I claimed for myself mental illness as part of my identity—no more apologies—no more self-conscious squeamishness—no more self–hatred. In effect, I declared: “I’m crazy. I’m here. Get used to it.” I draw enormous support from queer theory. I do not believe it is a coincidence that Foucault applied his methodology to both sexuality and to mental illness. Nor, it would seem, is it a coincidence that “homosexuality” was once catalogued as a mental illness in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). It would anger me to find that queers reject my claim for queerness, for if I were marginalized even from the margins, where would I go?

Just as writers write in ways that are conditioned by their contexts, so I must read this week’s readings in ways that are conditioned by my context. I read in order to glean insights which may be helpful to me. This is not self–centered. I hope that the conclusions I draw may, in turn, be held in conversation with those whose primary concern is sexual identity. Then, when I talk back to queer writing, it may hear things grounded in the particularity of my context which it may find meaningful in its own.

Beginning with “Coming Out: Journey Without Maps,” Carter Heyward offers me two points of reflection. First, she acknowledges the givenness of our sexuality, but given from such a wide base of sources that the notion of clearly defined sexual categories becomes impossible. Categories like “gay” and “straight” diminish us. “For these categories can be boxes; they can be imposed from without, not truly chosen, not reflective of who we are or might have been or might become”. While sexual identity may have a givenness, Heyward seems to imply that the validity of a descriptive category comes from its chosenness. By analogy, it is one thing for the medical establishment to impose its terminology on the basis of often ambiguous criteria set out in the DSM; it is quite another for me to choose for myself the label which I will use to claim (part of) my identity.

Heyward’s second point of reflection comes from refiguring sexuality, not as an accidental feature of living which can be foregone if necessary, but as “the one most vital source of our other passions”. The intimacy of sexual sharing reminds us in the most basic way that we are not alone. She uses this discovery to couple love with justice. “[J]ustice is the moral act of love”. This is a truth I have confirmed negatively. In the deepest of depressions, confined within an intensive observation unit, I visited the extremities of dissociative experience. Not only was I detached from those around me, I was detached even from myself. I could not identify myself in a mirror. But most disturbing was the fact that I could feel almost nothing. There was one feeling, however, which could give me energy—rage. Rage is the opposite of justice. Rage is a lashing out of incoherence. Disconnected and angry, love was impossible.

The pathology of the dissociative experience finds its mirror in the modern western description of mind/body dualism. In “The Third World, The ‘Third Sex,’ and the Third Way,” James S. Tinney rejects this traditional dualism, advocating an integrative view of embodiment which no longer treats spirit and body as warring opponents. Desire is both natural and good. The sexual fulfillment of desire is symbolic of union with God. This is reminiscent of Heyward’s view that sexual intimacy persuades us that we are not alone. From the perspective of psychiatry, the fact that one can feel anything at all is good; the fact that one can feel the touch of God is blessing. But Tinney is well aware of the psychiatric harm of enforced dissociation. He notes that the traditional Christian teachings which equate sex and sin reduce God to “trivial legalism.” More pressing are the “5 D’s” of ethical concern which arise from systems of evil. It is here that Tinney’s experience intersects with mine, for many of his “D’s” are manifestations of a “D” I hold for myself—depression. He writes of dread, which is “related to feeling that ‘nobody wants me,’ or ‘I’m not good to anybody,’ or ‘I’m not attractive.’” These statements typify the beliefs which permeate depressive thinking. Tinney also names “despair that causes suicide in our gay community.” Suicide is the most complete act of dissociation.

In his introduction to Jesus Acted Up, Robert Goss presents the notion of a gay/lesbian liberation theology which “begins with resistance and moves to political insurrection.” However, Goss must answer the critique that it is impossible to collapse the categories of gay and lesbian experience. Hence the value of the term queer. There are elements of common experience among gays and lesbians—homophobia and heterosexism, and the fact of political struggle. Queer is a term which enfolds these commonalities while acknowledging sexual diversity. But queer is more than a descriptive term; it is a verb describing acts of political dissidence which shake up institutions and blur the boundaries which such institutions seek to enforce. Queer is also about language, challenging the complacency which allows discursive practices designed to exclude. Part of its intent is to retrieve words which have come to be regarded as demeaning of those whose sexuality is different—words like “queer” and “faggot” and “faerie.” “Queer is transformed from a word coined against gay men and lesbians into an empowering, postmodern word of social rebellion and political dissidence.”

Goss describes the situation immediately following World War II, as gay men and lesbians began to assert themselves against homophobic institutions. Goss goes so far as to claim that, in its treatment of gay men and lesbians, the military service “created gay and lesbian bodies.” I am inclined to apply a more moderate interpretation to events. While the forced outing of large numbers of gay men and lesbians in the military service undoubtedly provided an early impetus to the process of forming discrete categories of sexual identity, nevertheless, this was probably a more organic process unfolding over several decades, emerging almost as a dialogue between events of resistance and events of oppression. I accept Goss’s conclusion: “Gay and lesbian identities were produced from the social effects of homophobic discursive practice.” Initially, acts of resistance were accompanied by demands for acceptance as normal, but with the Stonewall riots, those demands became calls for acceptance of difference. What began as an assertion of rights within a given social structure became a political movement aimed at reshaping that structure.

The shift in demands which followed the Stonewall riots finds a fuller articulation in Laurel C. Schneider’s article, “Homosexuality, Queer Theory, and Christian Theology.” Queer theory “take[s] on the whole paradigmatic system of meaning that produces heterosexuality and homosexuality in the first place and tend[s] to view religious ideas as cultural means of production for that system.” Queer theology may be necessary if gay and lesbian liberation theologies are to avoid “the mimesis that conditions homosexual inclusion in a heteronormative communion.” Justice is not merely fulfillment of the right to be treated as an equal, but fulfillment of the right to be honoured in one’s difference.

Can this shift be transposed to the experience of mental illness? Schneider certainly entertains the possibility, asking if queer thinking can “encompass a dynamic constellation of interrelated issues” including “disease politics.” The paradigm of mental health/illness is governed by a DSM normativity which is understood primarily in terms of behaviour. If behaviour draws a person beyond the American Psychiatric Association’s paradigm, then therapeutic procedures are indicated in order to draw the person back within the paradigm—a return to the psychonormative communion. Biblical models suggest the same approach within theological discourse. Jesus heals. In one way or another, we are sick, and Jesus brings us back to wholeness. We presume that healing of the body is a metaphor for a healing of the spirit. This is most apparent in the story of the blind man, Bartimaeus. The recovery of sight is customarily understood as a declaration that, among other things, Jesus has come into the world with the gift of insight. But what if the defect is so closely linked to the spiritual that the two are indistinguishable? What if the defect relates to mood, or anxiety, or visions? Of what use is a metaphor then? We typically understand the Biblical paradigm of wholeness as in opposition to the fractured frame of our fallen selves. The resurrection promise is raised up against the body broken on the cross. And so, for example, when Jesus speaks of anxiety and advises that we not worry for tomorrow, he could just as easily prescribe benzodiazepines, because psychiatric and religious normativities are aligned. But what if the “patient” is unresponsive to either treatment? What if the demon cannot be cast out, or controlled by pharmaceuticals? What if the vision, far from transforming a man into a believer, prompts him to yell at the top of his lungs? In these situations, wholeness is impossible within our accustomed paradigm(s). However, that does not preclude the possibility of wholeness. But it may require the recasting of the paradigm(s). It may require queer health. It may require queer religion.

I’m crazy. I’m here. Get used to it.