I regard myself as an inveterate interlineator, which is my 50 cent way of saying I scribble in the margins of books while I read. I first read Don DeLillo’s novel, White Noise, 10 or 15 years ago and made only one mark then. I corrected a spelling mistake on page 267 of my Penguin Paperback Edition. The mistake occurs during a dialog between the narrator, Jack Gladney, and his doctor who has discovered that Jack has a nebulous mass whose nebulosity may have more to do with semantic imprecision than with medical pathology.

“What is a nebulous mass, just out of idle curiosity?”

“A possible growth in the body.”

“And it’s called nebulous because you can’t get a clear picture of it.”

“We get very clear pictures. The imaging block takes the clearest pictures humanly possible. It’s called a nebulous mass because it has no definite shape, form or limits.”

“What can it do in terms of worst-case scenario contingencies?”

“Cause a person to die.”

“Speak English, for God’s sake. I despite this modern jargon.”

And … the typo ruins the punchline. It’s the only typo in the whole book, and yet it has to happen here! Right in the middle of the goddam punchline. There’s a reason bad copyediting used to be a capital offence.[1]

This week, I read the novel again, remembering from my first time through (the time when I made only one interlineation) that it might have some bearing on our shared experience in the face of a global pandemic. This time, in contrast to my first reading, I scribbled or underlined passages on every second or third page. It seems a global event with consequences that directly affect me is just the thing to make me read with piercing acuity. I bite my lip and I clutch at my pencil until my fingers hurt. The text is ever so much more meaningful.

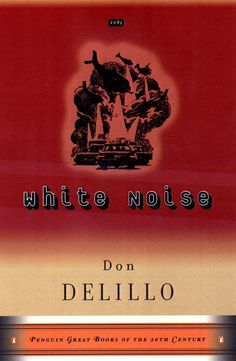

But first, let me offer a review of the book, White Noise. As I already said, I have the Penguin Paperback Edition. The cover has flaps, which I appreciate because they can double as book marks. The dimensions of the cover are 14.2 cm wide, 21.4 cm long, and 2.1 cm thick. Because DeLillo is an American author and because he is principally concerned here with American consumer culture, it might be more appropriate for me to offer the book’s dimensions in American measures: it is 5 9/16 inches wide, 8 3/8 inches long, and 13/16 inches wide. It weights approximately 400 grams which is 14.1 ounces. At the top of the front cover is a small black box enclosing the date, 1985. Apart from the book’s title and author’s name, the only text appearing on the front cover is “Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century” bookended, so to speak, by two Penguin penguin logos, mirror images, each facing the centre of the cover. The art work, by Andrew Davidson, depicts the novel’s principal event, a derailment resulting in the release of a toxic cloud of Nyodene D. Helicopters with spotlights hover around the cloud while cars flee the scene. The cover’s background colour is rust in the top two thirds and ochre in the bottom third with a gradient transition between the two colours. On the back cover is a photograph of the author (Mr. DeLillo has a handsome chin bum just like John Travolta), the novel’s opening sentence reproduced in an off-white font colour (“The station wagons arrived at noon, a long shining line that coursed through the west campus. In single file they eased around the orange I-beam sculpture and moved toward the dormitories…”), the price both in the U.S. and CAN, ISBN number and scanning code, and the publishing tagline (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century”) repeated along the bottom, as if to suggest that prospective readers are too stupid to have gotten that from the front cover. Again, the tagline is bookended, so to speak, by two Penguin penguin logos, mirror images, each facing the centre of the back cover. The spine features the following words:

- 1985

- Great Books

- DeLillo

- White Noise

At the bottom of the spine is another Penguin penguin logo. This penguin faces left. The pages are cream coloured, of enough weight to suggest quality, and deckle edged. Text font appears to be Garamond. On the interior front flap is a brief description of the novel in a cream coloured font. Sadly, the description includes a statement for which there is no evidence. It reads: “Jack and his fourth wife, Babette … “ However, on page 203, we learn that Jack’s first and fourth marriages are to Dana Breedlove. Babette could be his fourth wife, but only if his second and third wives are different people and there are no intervening marriages between his marriage to Dana Breedlove and his marriage to Babette. However, there is nothing in the novel to indicate that these conditions obtain. This means that the assertions on the front inside flap cannot be supported by the text. Babette may be Jack’s fourth wife, but it’s just as plausible that she is his fifth wife. Despite one typo and one factual imprecision, the book makes a fine commodity, especially when compared to other books of comparable length, like Geoff Dyer’s Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, which is printed on paper worthy only of pulp fiction.

But enough of book reviews; let’s move on to more substantive concerns.

As I stated above, I want to hold up White Noise because White Noise holds up concerns that speak to our current state of affairs, especially as it is playing out in DeLillo’s America. Novels like this one refute the widespread view that, as circumstances play closer to the bone, the arts and more general cultural pursuits are expendable. On the contrary, they sustain us. And when power seeks to exploit disaster, we look to the arts for our prophetic voices, those who will ground authority by exposing folly and drawing us back to the centre. In White Noise, DeLillo does this through satire.

The novel opens on an idyllic midwestern American college town where the narrator, Jack Gladney, is head of the Hitler Studies department, a department he has established from nothing by sheer dint of his determination. Despise his academic credentials, he cannot read or speak German, so spends much of the novel taking German lessons and lugging a copy of Mein Kampf wherever he goes. He is married to Babette and they live with four of their six children from various marriages. The first third of the novel introduces us to the family’s middle-class, mildly pretentious lifestyle characterized by its obsession with media, advertising, and fitness. The text is punctuated by jarring interpolations. For example:

She is afraid I will die unexpectedly, sneakily, slipping away in the night. It isn’t that she doesn’t cherish life; it’s being left alone that frightens her. The emptiness, the sense of cosmic darkness.

MasterCard, Visa, American Express.

I tell her I want to die first. I’ve gotten so used to her that I would feel miserably incomplete.

The triad of credit cards in the middle of a conversation about the fear of death is enough to induce ontological whiplash. And yet, in other contexts, we experience this jarring effect all the time. We see it on TV: four out of five dentists recommend brushing with Colgate, and now back to Sophie’s Choice where we will watch a mother consign her daughter to the Nazi death camps. We see it on billboards that point the way to the local casino as we drive through the rolling countryside. We see it on our smart phones: advertisements for AWD 4X4’s posing as posts from our rugged friends. In other contexts, we have become so inured to the disjointed narrative of consumer culture, why should it surprise us when the same disjointed narrative practice appears in our novels? Why have publishers been so slow to sell advertising space in books? Tampons in The Handmaid’s Tale? Legal services in The Trial? Goodyear tires in Lolita? The curious thing about the phrase, MasterCard, Visa, American Express, is that it reads like a liturgical incantation in a religious service. It’s a practical example of what Harvey Cox famously describes in his 1999 Atlantic Monthly article, “The Market as God.” If late capitalism is a religion, then the writers of ad copy are like the disciples after Pentecost, running out with their pithy phrases, converting all the world.

When the event happens, the release of airborne toxins into the environment, no one can quite believe it’s really happening. As Jack observes to Babette:

“These things happen to poor people who live in exposed areas. Society is set up in such a way that it’s the poor and uneducated who suffer the main impact of natural and man-made disasters. People in low-lying areas get the floods, people in shanties get the hurricanes and tornadoes. I’m a college professor. Did you ever see a college professor rowing a boat down his own street in one of those TV floods?”

And later:

“I’m not just a college professor. I’m the head of a department. I don’t see myself fleeing an airborne toxic event. That’s for people who live in mobile homes out in the scrubby parts of the county, where the fish hatcheries are.”

This could easily pass for a Covid-19 response. It won’t touch us; it’ll get old people, or people in dirtier parts of town, or foreigners, or local people who are foreign-looking. But it won’t touch us.

When it becomes clear that Jack can’t bargain with an airborne toxic cloud, he and Babette and the four kids climb into the family car and head for the highway. Jack stops for gas and is exposed to Nyodene D. for two and half minutes. At the shelter, an intake officer screens Jack and their conversation verges on the absurd, reminiscent of conversations between Yossarian and Milo Minderbender in Joseph Heller’s Catch-22:

“There are known degrees of exposure. I’d say their situation is they’re minimal risks. It’s the two and a half minutes standing right in it that makes me wince. Actual skin and orifice contact. This is Nyodene D. A whole new generation of toxic waste. What we call state of the art. One part per million million can send a rat into a permanent state.”

…

“That’s quite an armband you’ve got there. What does SIMUVAC mean? Sounds important.”

“Short for simulated evacuation. A new state program they’re still battling over funds for.”

“But this evacuation isn’t simulated. It’s real.”

“We know that. But we thought we could use it as a model.”

“A form of practice? Are you saying you saw a chance to use the real event in order to rehearse the simulation?”

“We took it right into the streets.”

“How is it going?” I said.

“The insertion curve isn’t as smooth as we would like. There’s a probability excess. Plus which we don’t have our victims laid out where we’d want them if this was an actual simulation. In other words we’re forced to take our victims as we find them.”

It’s a wonderful reversal: a simulation relies on real disasters in order to improve the quality of the simulation. It’s the sort of thing Donald Trump might find plausible.

The balance of the novel—and this is implicit in all the quotations I’ve gathered thus far—concerns itself with death. The problem with death, from the perspective of late market capitalism, is that it reduces the number of consumers, flattening the demand side of the marketplace. This is just the sort of thing you’d expect from law-and-economics analysts. Think Richard Posner, formerly a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit, who once observed that the chief benefit of marriage is that it reduces the transaction costs of sexual intercourse. This is the quality of ethical analysis late market capitalism brings to the conversation. It invariably seems to be a matter of secondary importance that the concern under discussion has real world consequences for real human beings.

We observe America’s commander-in-chief engaged in similar discussions, bringing a similar quality of ethical analysis to bear upon the issue at hand. One option under serious consideration is the “herd immunity” scenario in which the Covid-19 virus is treated much like a market ideology—laissez faire, allowed to run unimpeded through the entire American population, killing millions but leaving the survivors immune (at least in the short term). Trump effectively endorses this approach when he suggests that things will open up by April 12th for no better reason than that it would be “beautiful” to let people crowd into churches on Easter. The unintentional benefit of this approach is that the disaster would provide accurate statistics which would make future simulations more realistic. But given the U.S.’s current level of demonstrated competence, they’d probably fuck that up too.

It turns out that Babette is afraid of death and eases her fear by taking an experimental drug called Dylar. As one would expect, she first discovered Dylar by answering an ad in a tabloid. So desperate is she to maintain access, she sleeps with her supplier. However, the drug proves ineffective in any event. At the same time, Jack grows obsessed by the fact that he was exposed to Nyodene D. for two and half minutes. More precisely, he is obsessed by the certain death that such exposure guarantees, even though the approach of this death is stealthy and happens by such tiny increments that it may take as long as the span of a natural life. The obsession with death, the barrage of market brands, the cacophony of product jingles. This is the white noise.

White noise is a wonderfully synaesthetic phrase. It is the buzz of a thousand different frequencies sounding all at once. By describing sound as white, it invokes a metaphor: white is not a colour but a composite of colour, a thousand different electromagnetic frequencies assaulting the eye all at once. When the assault threatens to overwhelm us, one response is to remove all the colour. Jack Gladney’s colleague, Murray Jay Siskind, functions like an allegorical character who represents the principal of desaturation. Murray and Jack converse in a supermarket where Murray purchases generic products in white packaging and justifies his shopping preference with:

“I feel I’m not only saving money but contributing to some kind of spiritual consensus. It’s like World War III. Everything is white. They’ll take our bright colours away and use them in the war effort.”

Much later in the novel, Jack recalls another conversation with Murray concerning their colleagues:

“Murray said that Elliot Lasher had a film noir face. His features were sharply defined, his hair perfumed with some oily extract. I had the curious thought that these men were nostalgic for black-and-white, their longing dominated by achromatic values, personal extremes of postwar urban gray.”

It should come as no surprise that Babette’s lover/drug supplier is named Mr. Gray. I am reminded of Albert Camus’ observation in a similar context that “Plague had killed all colors, vetoed pleasure.” When we are overwhelmed, not only by crises, but by the daily flood of advertising, consumer culture, social media, screams for attention, one way to cope is to isolate ourselves. We wear earbuds to control the sounds entering our ears. We dream (and photograph) in black-and-white. We press our hands to our ears. We put out our eyes.

A concept which might capture the thrust of DeLillo’s novel is “culture of death.” This is a phrase that comes from Pope John Paul II’s 1995 encyclical, Evangelium Vitae. Coming ten years after the publication of White Noise, the concept was not available to DeLillo, at least not in such an explicit form. I should add that I am not Roman Catholic and do not care for the precise concerns of the encyclical. Nevertheless, as a general description of contemporary culture and the way we have allowed it to overwhelm our bodies, our spirits, our relations with one another and the world around us, I find it apt. The Covid-19 pandemic has brought the notion of “culture of death” into sharp relief. President Trump draws the logic of the marketplace to its absolute limit, demonstrating his dedication to the proposition that all men (and women) are subordinate to the American economy. Dan Patrick, GOP lieutenant governor of Texas, offers a variation on that theme with his call for Texan seniors to sacrifice themselves so that the country can “get back to work.”

The chief difficulty with DeLillo’s novel is that he wrote it as satire. What he envisioned as extreme and absurdist now plays out daily in our news. His novel now seems mild when set against the white noise of our everyday experience.

[1] I just made that up. There was never a reason.