In 1959, Tibetans staged an uprising against the occupying forces of the Communist Chinese Party. In the words of just about any Star Wars movie, the imperial forces crushed the rebellion. With help from the CIA, the Dalai Lama fled the country and has lived in exile ever since. Among other things, the Chinese army razed most of Tibet’s monasteries, destroyed or looted artifacts, and either killed or disappeared hundreds of thousands of monks. This was part of a larger effort to suppress Tibetan culture and to effect an erasure of local identity that is playing out again with the Uyghurs and, without Western intervention, may play out one day in Taiwan. At the same time, China was struggling with a widespread famine that lasted until 1961. While Chinese authorities at the time attributed the famine to environmental causes beyond its control, outside analysts have always maintained that it was the consequence of central policy decisions which could have been reversed. While we have no idea how many died, casualties probably number in the tens of millions and subjugated territories like Tibet were the most harshly affected.

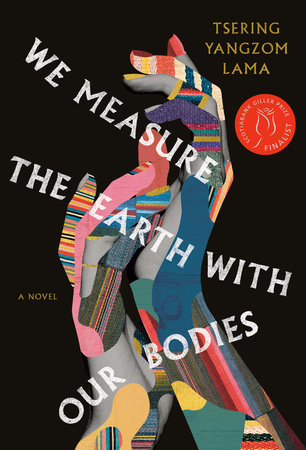

It is against this backdrop that Tsering Yangzom Lama opens her novel of diaspora Tibet which is among the finalists for the 2022 Giller Prize for fiction. At the outset, we have no sense of the larger political context. This is understandable given that she focuses on the lives of children. It is only as they grow older and have children of their own that they (and we with them) become aware of the larger forces that shape their lives. It is 1960 and Llamo and her younger sister, Tenkyi, are fleeing with their parents across the southern border of Tibet into Nepal. In the winter, their father’s feet turn black and gangrenous and he dies. When their mother, renowned as an oracle, also dies, the orphaned girls fall under the care of an uncle, Ashang Migmar. As the group of refugees enters Nepal, they are assigned a plot of ground, barely fertile, where they establish an encampment. Another refugee named Po Dhundup joins them there and becomes fast friends with Ashang Migmar. Po Dhundup lost his wife and children to famine and, afterwards, in his wanderings, he came upon a destroyed monastery where, among the rubble, he discovered a small mud statue, a ku, which he calls the Nameless Saint and which he looks to for comfort and healing. The Nameless Saint enjoys a furtive life amongst the refugees, offering a powerful connection both to the land they have come from—it is, after all, fashioned from Tibetan mud—and to the spiritual tradition they feel slipping away from them. A boy named Samphel appears in the camp, Po Dhundup’s nephew, bearing the twin stigma’s of illegitimacy and a father who has joined the military and now acts against his own people. Everyone agrees that one day the Nameless Saint will belong to Samphel. By the end of the first section, Lama has introduced us to the two threads she will weave through to the end of the novel, the uneasy relationship between Llamo and Samphel, and the fate of the ku which I think we are free to take as an avatar for all of Tibet’s spiritual traditions.

In the second section, Lama transports us to Toronto fifty years after these children first settled in a refugee camp. For me, the shift seems jarring. One minute, I’m reading about a people descending from the high plains of Tibet, a part of the world I know nothing about. The next minute, I’m reading about a world within walking distance of my home: the well-heeled streets of Rosedale, a stroll along Bloor Street, Devonshire Place and the U. of T. campus, Queen’s Park. Maybe my reaction is a function of my own comfortable life. If I had the wrenching experience of forced displacement, I might choose to reflect that in my writing with precisely the jarring shift Lama uses.

As a student, Tenkyi had shown promise, and so the camp raised enough money to send her abroad. She was the camp’s great hope. That is how she ended up in Toronto. For reasons that remain vague—maybe the burden of being a people’s hope, or maybe the lingering trauma of her refugee experience—, Tenkyi has failed to meet the expectations imposed on her. Instead, she earns a meager living performing menial tasks. She shares an apartment with her niece, Dolma, Llamo’s daughter. In a way, Dolma has become the person Tenkyi was supposed to be. She is smart, a good student, and she has caught the attention of her professors. One of those professors invites her to a party at a swanky Rosedale address, thinking it would give the girl an opportunity to advance her academic goals. The hosts are wealthy collectors of antiquities who support academics and museum curators. A woman who acts as assistant to the hosts invites Dolma to her offices in a corner of the house far from the party where she opens a safe and shows Dolma their latest acquisition. Although Dolma has never seen it herself, she believes the artifact is the Nameless Saint; she has heard so much about it from her family.

Dolma walks off with the ku, assuming it is a stolen artifact and needs to be returned to the people of Tibet. It’s a matter of puzzlement then when Samphel tells her she must return the artifact to the wealthy couple who live in Toronto. Although Tsering Yangzom Lama started working on this novel ten years ago, it is fortuitous that its publication should coincide with a larger conversation about the decolonization of Western museums and galleries with special attention to the provenance of antiquities. We’ve almost reached the point where we can presume that an artifact has been acquired by theft unless the holding institution can establish otherwise. Given this conversation, we can understand why Dolma responds with indignation at Samphel’s instruction. At the same time, we might expect Lama to become a bit didactic or even self-righteous in her approach to the issue. To her credit, she exercises restraint and allows the story to speak for itself.

It turns out, the ku’s provenance is murky, and any efforts to give it clarity don’t yield simple good/bad, right/wrong dichotomies. Yes, the artifact properly belongs to the Tibetan people, but forced from their land, they had no permanent structures like temples where they could house it. The Chinese would have destroyed it had a Tibetan not retrieved it from the rubble so, properly speaking, it was rescued, not stolen. When it fell into Samphel’s hands, there may have been a tacit understanding that he held it in trust to the Tibetan people, but practical exigencies intervened. He wanted a better life both for himself and for the people he loved. He needed money. Why not leverage some last bits of his heritage? At least by selling it to antiquities collectors in Toronto, he ensured it would find a place of stability and security. The conversation is further complicated by the fact that the ku is not simply an artifact but a religious icon. It is ancient and may have accumulated wisdom all its own as it passes from hand to hand. In fact, it may possess a will of its own that subtly directs its fate. Perhaps only the ku can say where it properly belongs.

Parallel to the concern about the return of an antiquity to its people is the concern about the return of a body to the land. The final section of the novel relates the second of Dolma’s “failures.” Dolma receives word that her mother, Llamo, has died and so she travels to Nepal but too late for the funeral. She arrives as the pyre’s flames sputter out just beyond the boundaries of the refugee camp. In another deception, Samphel passes off sand as the ashes and gives the urn to Llamo’s uncle Ashang and keeps the real ashes for himself. Together, he and Dolma embark on a journey through Nepal to the Tibetan border with the vague hope of returning her ashes to her homeland. As one would expect, they can’t cross the border. The closer they get, the more exposed they become and the more they risk detention. The best they can do is cast the ashes on the Nepal side of the border with Llamo’s homeland in view. Just as there is no return for an icon to its people, so there is no return for the Tibetan people to their land. It is at this moment the reader gains some sense of what it means to be a people in permanent exile.

Of all the books shortlisted for the Giller Prize, Tsering Yangzom Lama’s is the only “big” novel. By “big” I mean that it has a certain emotional heft, a historical sweep that draws us into the concerns of an entire people while at the same time relating those concerns through carefully wrought individuals who capture our empathy. It’s a wonderful achievement, hard to believe it’s a first novel.