Joey Comeau’s first novel was Overqualified, which I looked at here. He’s come out with two novels since then, & I picked up both from the ECW Press booth at Word On The Street last September. The first is One Bloody Thing After Another. It’s suburban horror (what other kind of horror is there?). Mom hocks up a bloody clot of something that signals more than just an illness. The kids lock her in the basement and feed her, but it soon becomes apparent that mom won’t eat her meat if it’s dead. It’s hard to supply a grown woman with live animals when you’re trying to keep up with school. Nevertheless, the kids manage to find kittens, a dog, even a baby. Meanwhile a senior named Charlie (whose dog mysteriously disappears) receives daily visits from the ghost of a young woman who holds her head in her hands. Every day, she points Charlie to a neighbour’s room in the old folks home, mouthing a message she wants him to deliver. The neighbour can’t see any ghost and Charlie has no idea what the ghost is mouthing, so he can’t make sense of her message. One Bloody Thing reads like an extended joke, complete with punch line on the last page. It’s a fun read, very much in the spirit of Kelly Link.

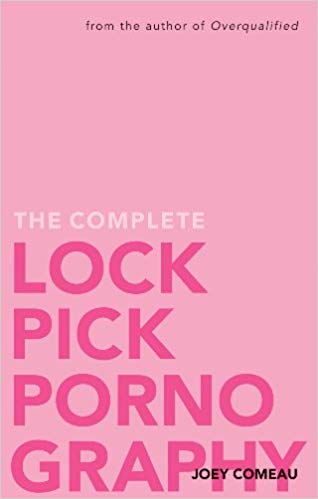

The second book, The Complete Lockpick Pornography, reads with the same breezy style, but has more meat on its bones, so to speak. The publisher describes it as a genderqueer adventure story, which, although accurate on its face, increases the likelihood that it gets relegated to the genderqueer literary ghetto, a fate it doesn’t deserve. The book is two novellas, Lockpick Pornography and We All Got It Coming. The narrator of each identifies as genderqueer. Through their eyes, we witness the prejudice they face and the seemingly inevitable violence that prejudice produces. However, the narrators differ in their responses to the violence.

Lockpick Pornography opens with a boot through a TV set and the observation: “I stand there wondering why I let my belief that violence only makes things worse prevent me from being violent.” S/he performs a series of pranks designed to queer heteronormative assumptions. This culminates in the kidnapping of an eight-year-old child, son of the local fundamentalist preacher, a man who frequently pontificates on TV about traditional family values. The son is a prop in his father’s public moralizing. A queer intervention seems appropriate.

We All Got It Coming moves in the opposite direction. A disgruntled customer at an office supply store calls a sales clerk a faggot. Afterwards, the clerk explains to his manager that he’s gay and didn’t like being called a faggot. The manager offers up an overblown reaction (pushing the clerk down the stairs) and when the smoke clears, the clerk finds himself on the horns of a dilemma. If he reports the manager, then the manager will be fired and the incident will further entrench his prejudices. If he does nothing, the manager will be relieved and everybody will get to avoid a big confrontation. The clerk opts for non-confrontation. He doesn’t report his manager, but he can’t stomach going in to work the next day either. As the story progresses, it becomes apparent that the manager is entrenched in his prejudices no matter what the clerk chooses to do. People who are assholes rarely stop being assholes. By avoiding confrontation, the clerk has allowed the manager to be an asshole with other people too.

Polarizing confrontation? Or passive resignation? One would like to think there is a third way that challenges without alienating.