On Saturday afternoon, my wife and I put on our masks and went out to get some supplies. For us, these outings double as opportunities to get exercise after long stretches cooped up in lockdown. Like everyone else, we’re frustrated. We feel like we’re in limbo. Still, we wear our masks; we keep our distance; patiently, we wait for more shipments of vaccine.

After finishing our errand, we kept on walking, exiting the Cumberland Terrace and continuing on to Bay Street. There, we turned south to Bloor, then headed east thinking we’d return home. We heard shouting behind us and turning around saw a mob approaching from the west. I had my little Sony mirrorless camera in hand so, naturally, I wanted to get some shots. Thinking the best position would be on the south side of the street, I dragged Tamiko across Bloor and together we waited by the entrance to the Manulife Centre. That way, if we felt uncomfortable, we could duck inside and make our escape underground. Ever since I placed Tamiko at the centre of the Black Bloc uprising during the 2010 G20 Summit, she has never felt comfortable being near me when I have a camera at a protest.

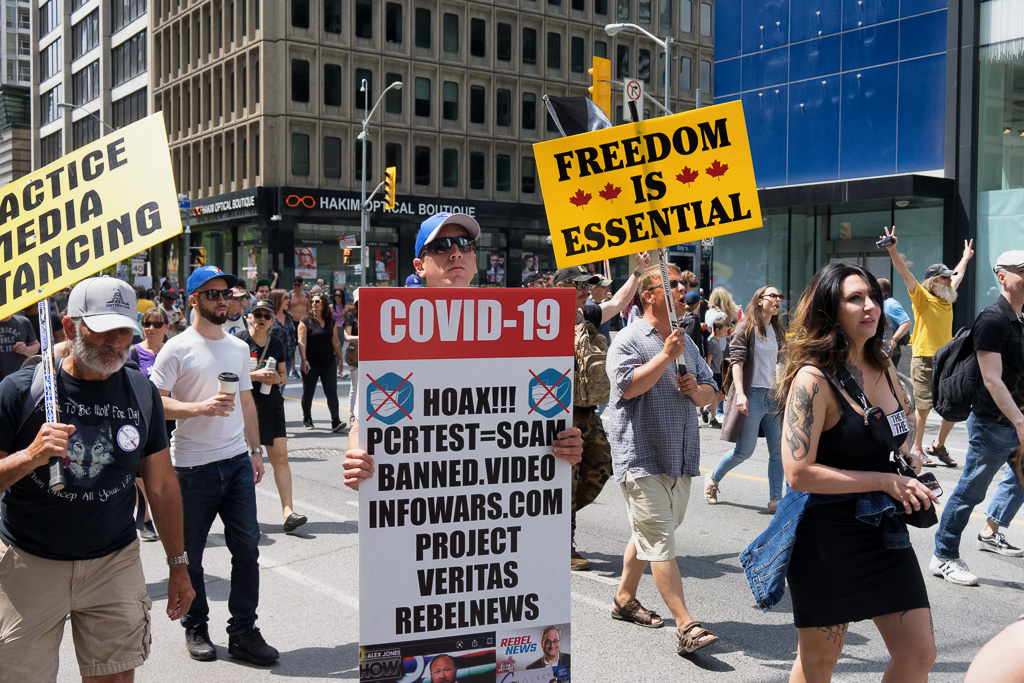

As the mob approached Bay Street, police officers blocked traffic to let the protesters through the intersection. Tamiko retreated to the doors of the Manulife Centre. I moved in the opposite direction, stepping into the street and allowing all the maskless protesters to flow around me. I took a certain delight in flaunting my mask. I didn’t have to say anything to make it clear what I think of the anti-mask perspective. For the most part, people didn’t mind that I was standing in their midst, only a handful of people were verbally aggressive. A handful of people is not bad when you consider that the mob went on and on and on. I’m no good at estimating numbers attending events like this, but I’m certain there were thousands.

The Anti-masker/Anti-Asian Nexus

On May 10, the National Post published an article relaying a statement from NDP leader, Jagmeet Singh, drawing a connection between anti-masker demonstrations and far right extremism. He was echoing studies that establish a clear overlap between anti-masker and anti-vaxxer views which, together, provide fertile ground for those promoting far right politics, white supremacy, neo-nazism, conspiracy theories, and racial hatred. If I were to offer a profile of the demonstrators, my admittedly unscientific survey would acknowledge the presence of the occasional Black (3) and Asian (2) participants. However, in a crowd comprising thousands of otherwise Caucasian participants, it can hardly be called a representative group, certainly not representative of the Toronto populace. It was overwhelmingly white. Signs referred to Rebel Media, Maxine Bernier, questioned mainstream media, said the government (& Trudeau) isn’t to be trusted, challenged vaccines, and even questioned the body count. While some of the signs offend reason, and while others offend a sense of human compassion, to my eyes, the most offensive sign is the one that read “Chinada”. It makes explicit a sentiment that otherwise flows freely underneath the surface of all this shouting.

Covid-19 is intimately tied to anti-Asian sentiment. Almost the instant the WHO confirmed that the SARS-Cov-2 virus had originated somewhere near Wuhan, people made the leap from statements of fact to statements of blame. Somehow, it seemed important that this be somebody’s fault. Who better to blame than Chinese people? On March 16, 2020, Donald Trump threw gasoline on the fire by using the #ChineseVirus hashtag in a tweet. Later, he referred to it variously as the China flu and Kung flu. People made the further leap from a geographically specific blame to a generalized contempt for all things Chinese. Locally, people avoided Chinese stores notwithstanding the fact that those stores had no connection, geographic or otherwise, to the source of the virus. From there, it was another short leap to slurs against Asian people generally. Things came to a head when, exactly one year after Trump’s #ChineseVirus tweet, a 21 year old gunman killed 8 women in three different massage parlours in the Atlanta area. News reports identified six of the women as Asian. By then, Trump was banned from Twitter so he had less reach, but he still got some play that evening on Fox News when he used the term “China Virus.” Studies have demonstrated a clear connection between Trump’s incendiary statements and violence to people who look Chinese.

Well intentioned people have pushed back. In the week following the Atlanta shootings, a Caucasian man stood on the street corner near my home holding a sign: “Stop Asian Hatred.” Who wouldn’t want to stop Asian hatred? It reminds me of the running gag in Miss Congeniality about how virtually every Miss America contender wants World Peace. It’s a cliché so closely tied to success on the beauty pageant circuit that it might as well be oxygen; without it, a contestant’s chances would wither. After all, who wouldn’t want world peace? There’d have to be something wrong with a person who didn’t want world peace. In the same way, what vaguely liberal-minded person of good will wouldn’t want to end violence against people in the Asian community?

The problem with a vague intent is that it has no connection to the storied lives of real people, especially when terms like “Asian community” are regularly trotted out by the media. In high school, I had a Korean friend who, on graduation, went straight to the police academy and became the Metropolitan Toronto Police force’s first Korean-Canadian officer. The higher-ups were eager to have him act as liaison between the police and the Asian community. He told me about giving talks at high schools and, afterwards, being approached by Chinese students who wondered quite bluntly what the hell he was talking about. Born in South Korea and emigrating to Canada with his parents while still a young boy, he knew as much about Toronto’s Chinese community as I do. The fact is: there is no such thing as an Asian community, any more than there is such a thing as a WASP community (as a short visit to Derry will amply demonstrate). There are only Asian communities. Plural.

A Visit to the Japanese-Canadian Cultural Centre

As a WASP, I have no direct experience in these matters, but I come to it the best way possible: through love. More than that, the object of my love is mixed race, so the importance of a plural perspective wakes up beside me every morning. In 2015, one of the lawyers Tamiko works for was appointed Honourary Consul for Singapore and invited Tamiko to help set up a consulate in Toronto. It didn’t mean a change in employment, only in duties. I was delighted because, when Tamiko got sent on training junkets, first to Manhattan and later to Singapore, I went along for the ride and spent my days doing street photography in some of the most street photography friendly cities in the world. An interesting fact about Singapore (at least from my perspective) is that one of the architects of Singapore’s independence was a mixed-race man named Barker. For people using the consulate’s services who were aware of the country’s history, it was natural to wonder if Tamiko Barker was related, perhaps a granddaughter.

One of the perks of Tamiko’s job might best be described as the “consular schmooze circuit”, a neverending roster of social events designed to keep the business and social worlds connected even as their political representatives do their very best to burn things to the ground. It is physically impossible for any one consul to keep up with all the invitations and so one of the solutions is to slough off some of the events to the assistant. Naturally, I’d attend as Tamiko’s plus one. Or arm candy if she was in a charitable mood. So off we went to the Spanish Centre on Hayden Street to screen one of the hottest new films to come out of Argentina, all while sampling representative Malbecs. Another time, we went to the Ismaili Centre to mark the centenary of Afghan independence. I had a fascinating conversation with the Afghani Consul General’s daughter who at that time was a Fulbright Scholar at one of the big California schools, maybe UCLA. Chris Alexander spoke at the event and it was one of those rare occasions when I was impressed by a conservative. He was smart and he spoke Arabic. And yet, in succeeding weeks, he botched his election campaign, mostly by failing to keep his mouth in check, and lost his seat in a humiliating defeat. It was a strange outcome for a man who had been a respected diplomat.

Our most interesting invitation was to an event at the Japanese-Canadian Cultural Centre. It was interesting for an odd nuance that I’m sure most attendees, or at least most Caucasian attendees, would not have noticed. I wouldn’t have noticed either except for the fact that I have passed more than half my life with Tamiko and have made an effort to learn something of her family’s history. It was an event to acknowledge and celebrate Japanese investment in the Toronto area, especially in the west end of the city, and in Mississauga. However, I’m not sure why the organizers thought it would be a good idea to hold it at the Japanese-Canadian Cultural Centre when the ballroom at any airport hotel would have done just as nicely. The key to understanding my question is in the name. The venue is called the Japanese-Canadian Cultural Centre, not the Japanese Cultural Centre. A Japanese person is not the same as a Japanese-Canadian person because a Japanese person has not had their personal and cultural identity overwhelmed by a singular trauma aimed at eradicating them as a people. I stood in a room full of English-speaking descendants of the internment experience who were doing their best to entertain Japanese-speaking distributors of auto parts. In part, it was a funny scenario: people who looked like one another had nothing in common and, after the pleasantries were done, couldn’t think of anything else to say. In part, it was a sad reminder of how far the path has diverged for the Japanese who settled in Canada at the beginning of the 20th century. One can never assume that because people look similar and bear a similar label they therefore belong to the same community.

Tamiko and I were married in 1988. At that time, Brian Mulroney was the prime minister, another of those smart, well-spoken conservatives who may or may not have understood what consequences would flow from the flapping of his mouth. Nelson Mandela was still in prison and Archbishop Desmond Tutu had not yet articulated the principles of Truth and Reconciliation as a framework for bringing healing to oppressed peoples. Less than a month after our wedding, Mulroney issued a formal apology to those Japanese Canadians who had been interned during World War II. There was no process to engage in long-term healing. Tamiko’s mom and her aunt and uncle and grandmother each got a cheque in the mail.

Internment at Kaslo, B.C.

I try to imagine what it would have been like if the Government of Canada had tried to invoke a Truth and Reconciliation process to address the internment legacy, maybe mirror the work that Murray Sinclair has done in the context of the Residential Schools Genocide. I try to imagine it but invariably it devolves into sketch comedy. I imagine a touchy-feely leader going around the room asking who wants to go first and share their feelings. The leader turns from one stoney-faced person to the next. Not me. Hell no. Pass. Instead, they go for a drink or to shoot a round of golf. It’s my impression—another of those unscientific surveys I’ve conducted—that survivors of the Japanese-Canadian internment experience aren’t inclined to share their feelings about it. In 2011, Tamiko and I drove out to Kaslo, in the interior of British Columbia, the site of the internment camp where my mother-in-law and her siblings and parents were warehoused during World War II. When we returned from our visit, I asked Tamiko’s grandmother what she remembered of her time there. She said that it was very beautiful. She smiled and said nothing more.

Yes, Kaslo is beautiful. It is a small village set on a picturesque lake in the midst of a mountainous terrain. What makes it beautiful also makes it inaccessible and obviates the need for fences and guards. We stayed at the main hotel there. The original building on that site had housed roughly 300 people, but burned down after the war. It was rebuilt as a comfortable tourist resort with Jacuzzi tubs and turn-down service. On the morning after our arrival, we strolled through the village and easily located the house where the Kubas had lived with another family. Back in 1942, Kaslo was an abandoned mining town and when the Kubas arrived, they found old dishes still laid out on the kitchen table. It was as if the original occupants had been snatched away in mid-step, maybe raptured if you believe in that sort of thing.

Stripped of their property and deemed enemies of the state notwithstanding the fact that they all had been born in British Columbia and were Canadian citizens, the Kubas waited out the years and when they were released, were told they weren’t welcome in British Columbia. Either “return” to Japan or move east. For most of the interned, any connection to Japan was tenuous and so the choice was really no choice at all. Most moved east to restart their lives from nothing.

The trauma persists. Some remembrance is intentional. For example, annual dinners at the Japanese-Canadian Cultural Centre serve dishes from the internment years. One of the most popular items on the menu is spam sushi. In place of a strip of seafood, sushi chefs lay a slab of spam across a ball of sushi rice and wrap it with a strip of nori then serve it with wasabi and soy sauce. It hearkens back to their days in the camps when they couldn’t get fish. But other remembrance is harder to define, unspoken hurt bred into the bone, almost like DNA. There are moments in my marriage when I wonder if maybe, when I find myself in conflict with Tamiko, I’m not facing my wife alone, but facing the accumulated burden of a hereditary trauma instead. She turns silent or, like her grandmother, smiles at me and says that things are fine. In the absence of a collective process, like Truth and Reconciliation, that documents the hurt and makes it explicit, it’s sometimes difficult for me to tell whether I’m dealing with the ordinary stuff of two people in a relationship or the dregs of a racial insult that has trickled down the generations.

Then, there are the (mercifully rare) moments when the insult is more direct and more obvious. Like when we moved into a new neighbourhood and two (white) women walked away from Tamiko as she was pushing a stroller, pretending she didn’t exist, assuming she was the nanny. Or like walking at the local strip mall when a (white) man passed her then decided to turn back and spit on her.

So You’re Worried About Your Freedom

I’ve gone on at length with an account of the Japanese-Canadian internment experience for a couple reasons. The first is to illustrate that concerns for the “Asian community” aren’t intelligible when considered in the abstract but require the particularity that personal stories afford. Stories give flesh to the bare bones of memory. As with the beauty pageant call for world peace, the abstract hope for reconciliation along racial lines has no content without the specificity of a storied context. And there are at least as many stories as there are people. One could just as easily look for them in the experience of the Chinese who were recruited to work on Canada’s railway and, with the passage of the Chinese Immigration Act in 1885, found themselves subject to a head tax which effectively consigned them to indentured servitude. The legislation’s intent was to exclude Chinese people from Canada, but it didn’t work; all it did was make them miserable.

The other reason I’ve gone on at length about the Japanese-Canadian internment experience is that, at its heart, it concerns freedom. It’s legacy has become the touchstone for our country’s subsequent claims that it safeguards a free society. The anti-masker marchers routinely invoke freedom as a rationale for going without masks. It would appear that, in their view, personal freedom trumps collective responsibility. They even claim our veterans died for their right to go maskless. Yet when we set their view of things against a real deprivation of freedom—one that strips an entire people of all their possessions, dumps them in a remote location where it is impossible to flee, holds them there for years, and then, when it comes time to restore their freedom, does so by forcing them to resettle thousands of kilometres away—they look to me a lot like spoilt children. The very fact that we allow them to march down the main thoroughfare of our city gives the lie to their complaints. Admittedly, one of the marchers lost his freedom when he was arrested but that was because he bit a police officer. No, they are worse than spoilt children. They tie their whining to racist tropes. That makes them a social evil.