Yesterday, David Gilmour got himself caught up in an internet shitstorm. Unlike most of his detractors, I chose to let my opinions ferment overnight. I hope that leads to something more considered than much of the self-righteous anger I’ve read. Here are a couple things that might differentiate my opinion from others. First, I’ve actually read his novels (except the latest) and his memoir, Film Club. I come to the Gilmour shitstorm with an already formed opinion about his writing.

My pre-shitstorm opinion: Gilmour is a good writer. I think Lost Between Houses is the best coming-of-age/dysphoric-youth novel since Catcher In The Rye. (Although that might not be saying much if you don’t like Caulfield/Salinger.) Most of the other novels can be described as explorations of (straight) male sexuality. It is invariably dysfunctional. I read him as offering a critical commentary on the sexuality of the privileged white male. It would be a real stretch to read him as a straight-up cheerleader for privilege.

Second, he teaches English at Victoria College from where I got my English thingy. I have a vested interest in ensuring the continued quality of Vic’s teaching staff and programs. Pretty soon, they’ll be hitting me up for my annual gift. What should I say this time around? Money does talk, and if enough alumni say shit, you’ve got a real stinker, there, maybe they’ll do something about it. We’ll see.

The shitstorm arose in response to an “interview” in Hazlitt, a Randomhouse internet magazine. [Link no longer exists.] It felt to me like David Gilmour was playing one of his characters, kind of a parody of the privileged white male. Some of his statements are quite funny if you come to them the way you’d come to an episode of South Park. In fact, if Gilmour were a South Park character, he’d be Cartman. Here are some of his more Cartmanesque statements:

>> “I’m a natural teacher, I was trained in television for many years. I know how to talk to a camera, therefore I know how to talk to a room of students. It’s the same thing.”

>> “[W]hen I was given this job I said I would only teach the people that I truly, truly love. Unfortunately, none of those happen to be Chinese, or women. Except for Virginia Woolf.”

>> “I say I don’t love women writers enough to teach them, if you want women writers go down the hall. What I teach is guys. Serious heterosexual guys. F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chekhov, Tolstoy. Real guy-guys. Henry Miller. Philip Roth.” (After saying he loves Proust and his favourite volume is Sodom and Gomorrah.)

I assumed it was a publicity thing. But the vitriol went viral and forced an apology in which he made another batch of Cartmanesque statements. It was clear that Gilmour said what he said without the intent of being a troll, or gaming twitter for publicity, or whatever. He isn’t savvy enough to invent an online persona and stick with it.

Still, I wasn’t impressed with much of the writing in response to the interview.

People love to be outraged. The internet is the ideal environment both to locate causes of outrage and to vent that outrage. If we keep this up, outrage will be constituted as its own genre. The occasions for true moral outrage are rare, but we are addicted to the rush it gives us. We thrust manufactured media pratfalls onto the same field as slaughters and acts of war so we can get our fix of moral indignation. In doing so, we trivialize those occasions which do demand our outrage.

It may be too much to expect of the internet, but, in my view, a response ceases to belong in the sphere of civil discourse, and loses all credibility, the minute it engages in ad hominem remarks. Stick to the substance. Attack the man’s opinion. Don’t call him a douche or an asshole.

The problem with ad hominem remarks is compounded when the person does so for personal aggrandizement. Here’s a good example from someone I’ve never heard of named Maureen Johnson who uses the word “asshole” 14 times in her post (including the tag) and writes: “But I stand here as someone with a stupid MFA from an Ivy League school, and I’ve been a published author for ten years, and I’ve been with a bunch of publishers, and I’ve talked to thousands of people—librarians, teachers, readers, booksellers, non-readers, pundits, bloggers, agents, editors—about this problem [the treatment of women in writing] or just about publishing and I can tell you …”

Not even the self-deprecating word “stupid” can mask the play for reader approval. No, I don’t like David Gilmour’s words, but I don’t like these words either. If Gilmour is the internet’s festering wound of the day, then Johnson is one of its maggots growing bigger off the rot. Ditto for the person who produced the “interview”—a case of enhancing one’s reputation at someone else’s expense—if this counts as journalism, then journalism is a pernicious thing.

The Gilmour shitstorm is yet another in a seemingly endless series of instances of the internet’s polarizing effect on human concerns. In this case, the concern is masculinity. If we were to believe the internet, we’d have to conclude that there are only two kinds of masculinity. There’s the Gilmour kind. “Serious heterosexual guys.” “Guy-guys.” Then there’s the standardized PC kind. A vaguely effete (possibly gay?) but definitely sensitive artistic (insert stereotype here) masculinity. It’s impossible to consider masculinity as a spectrum, nor can we think of one person enjoying multiple masculinities. The weird pathologies of maleness that we encounter in such a polarized universe don’t offer much for men who want to be more than binary robots.

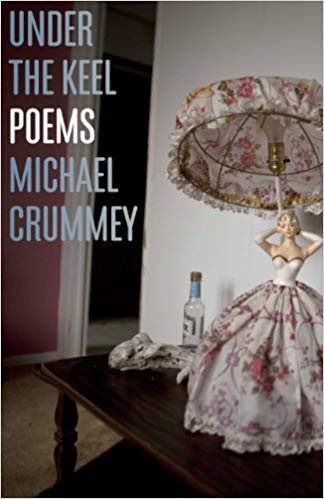

I’ll conclude by offering readers a literary presentation of an alternate masculinity, something sane and unpretentious, something near the middle of the spectrum. I could offer any number of examples; I offer this because I just finished reading it: Michael Crummey’s latest collection of poems, Under The Keel (Anansi, 2013). Yes, real men DO write poetry. His collection is filled with honest feeling and empathy, humour, nostalgia, and even one or two drifts towards the sentimental. But it’s filled with guy-guy stuff too, adolescent gropes, rescues at sea, and bottles of home-brew. But here’s the thing: the teenage reminiscences give way to something more. Crummey grows up. The collection has a narrative logic and we see it right from the start. In the poem titled “Boys”, we wander with a group of teenage boys, bored and making trouble in a rural town:

Half-grown, we were living our life by halves,

our dreams were vacant rooms we didn’t ownand roamed in silence, shadows behind dark glass,

our mute hearts a mystery to ourselves.

The rest of the collection works at the mystery; we accompany Crummey into an adulthood that owns the room it occupies.

Crummey was born in a mining town in the interior of Newfoundland, growing up there and in Labrador, so he comes honestly by the lyricism and lilt of his language. And he comes honestly by a clear sense of place, of rock and of water. So we have rock:

we just come up now

from heaving rocks

at the gulls down on the pointthe priest comes through one Sunday a month

and shag all to do after mass

so we goes to flick a few rocks

And we have water:

A second vessel worked close

enough to heave them a lineand we counted eight or nine

in lifejackets over street clothes,more again huddled at the back.

Lost sight of them in a troughjust as they tipped into the bleak

and the men pitched from the raft—

One of the complaints levelled against David Gilmour is that he insists on restricting his teaching (and his writing) to what he knows i.e. heterosexual middle-aged men. What about empathy? they ask. Isn’t empathy one of the reasons we have literature in the first place? Crummey doesn’t share Gilmour’s scruple and is willing to take risks. Especially in the section titled “Dead Man’s Pond,” he adopts the voices of other people, old men, old women, people who lived long ago but are dead now. His risks pay off.

In “Patience,” an old woman in a photograph talks the ear off an onlooker. And in “Women’s Work,” an old man tells how he has to care for his wife whose health is failing. “Mark Waterman, Lightkeeper (retired), Addresses His Successor Ca. 1931” is self-explanatory. In each, Crummey draws us inside a fresh experience. For a few minutes, we are Maritimers too.

The section, “Under Silk,” moves us into marriage, love, family life and children. In “Getting The Marriage Into Bed,” Crummey offers up a celebration of fleeting pleasures:

sneak out of your clothes

as soon as the coast is clear—the air raid siren of a youngster

crying is about to risethrough the bedroom floor

The poem ends with the ominous “You have less time than you think.” Death approaches with “Pub Crawl In Dublin” as the married couple travel to Ireland where the wife’s brother, stillborn, lies buried. And in “Vampires, Etc.” we witness Hallowe’en preparations which include “a counterfeit cemetery,/headstones for the faux-deceased.” The inevitable comes to fruition in “Under Silk” which opens: “My wife is dead, is dead, is dead …”

We come at last to “The Landing” and in the poem of the same name, Crummey returns us to the mystery he named at the outset. The poet is dreaming of his dead father and offers these words:

Our lives are simpler than we care to see.

Even in the thorniest circumstances,

we dismiss the heart as a mystery

to avoid ourselves

In accessible language, Michael Crummey offers us the privilege of witnessing a man maturing into midlife with dignity and decency. Under The Keel is a fine antidote to the whole David Gilmour shitstorm.