When the man woke, he turned to see the woman mouthing words at him from across their pillows. He could see the lips moving, and the tongue pushing the words out between the teeth, but he heard nothing. Maybe he had gone deaf in his sleep. But he recalled the jarring buzz from his clock radio. If he had gone deaf in his sleep, he would have slept through the alarm. He looked again at the woman’s lips and listened. He heard the furnace start with a clunk. He heard his feet pad across the hardwood floor. He heard the creaks of the floor as his weight stressed the tongue-and-groove joints. He heard the plash of water in the toilet and the gurgle as it all went down the drain. He heard the drizzle of the shower on the slate tile. He heard the dribble of milk across his cereal. He heard the swish of the tie he wrapped around his neck.

But when the woman spoke to him at the front door, he only noticed because he saw the lips move.

You’ll have to speak up, honey, he said.

The woman’s expression passed from affection to distress. She mouthed something again, this time with more vigour, as if the words she had mouthed now needed underlining.

I can’t hear you, the man shouted.

By the woman’s frightened look, the man surmised that she couldn’t hear him either.

The couple rode the subway together to their separate offices where they worked as professionals in their professional world. All the way downtown, they shouted at one another. Although the train was crowded, no one noticed how they shouted. The train rattled through the stations. The bell dinged when the doors opened and closed. The wheels screeched on the curves. A thousand footsteps shuffled across the platforms. But they could hear nothing of their own voices. When they paused to catch their breath—shouting is an exhausting thing to do—they saw how all the others around them were shouting too. Or at least going through the motions, for no sound came from their lips. Everyone was shouting, but no one could hear, so everyone shouted louder. By the time the man reached his stop, the people around him were slumped in their chairs, or clinging to the poles, worn out from all their shouting.

It was the same in his office. The man said hello to the receptionist, but she didn’t notice him. He began his workday with mild tones, but as those around him appeared not to hear, he spoke louder and louder until he screeched at his colleagues.

As the work day drew to a close, the man’s boss, who wore a blue suit, called him into the corner office where the man was summarily dismissed. The man asked why, but the man’s boss did not understand the question. In an impromptu game of charades and made-up signs, the man’s boss conveyed that the man was not very good at communicating. In recent days, he had contributed nothing fresh, but instead grew shrill by the minute. It was intolerable. Waving his arms, the man asked how his boss could say such things when the boss couldn’t—or wouldn’t—hear him in any event? What choice did he have but to shout? The man’s boss had turned away and didn’t notice the questions.

Over dinner, the man told the woman what had happened. Some of it he signed. Some of it he scratched onto pieces of paper. The woman was angry and after shouting her silent recriminations, she stomped from the room.

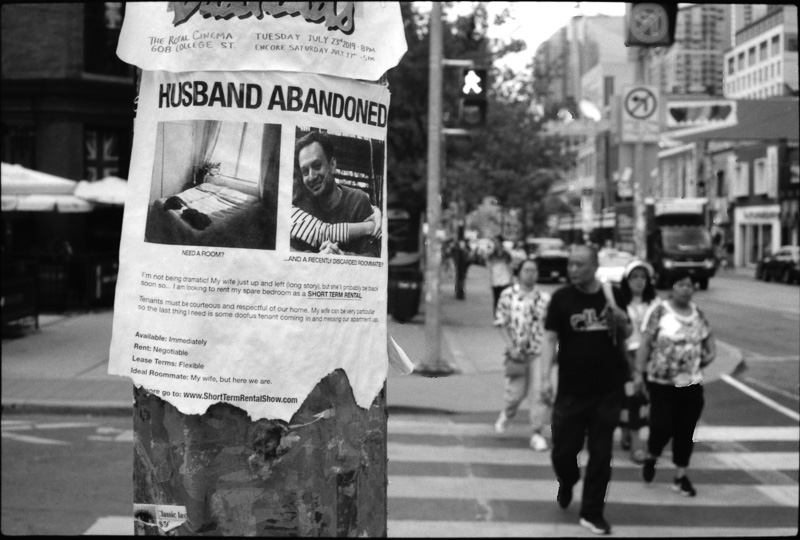

It seemed little time before the woman petitioned for a divorce. In the supporting affidavit, the petitioner complained about the respondent’s verbal abuse. The man answered that this was ludicrous; this was yet another instance of the woman’s habitual lying. So it went, back and forth, but nobody ever read the documents. The court house already stored mountains of such exchanges. There was nothing the couple could allege that hadn’t been alleged before.

Alone in his new apartment, the man turned on his TV. He kept the volume soft at first, but couldn’t hear what anybody said. He had no problem hearing the car chases and laugh tracks and creepy music and Foley artist bone-crunching sound effects, but when the actors spoke, there was no sound, only lips opening and closing. It reminded him of fish in a bowl. He watched the evening news and it was the same. He cranked up the volume, hoping he could hear what the news anchors reported, but it made no difference.

One morning, the man found an eviction notice taped to his door. All the neighbours had complained to the landlord about the noise coming from the man’s apartment. The man tried to explain to the landlord that he hadn’t meant to disturb anybody; it was a problem with his TV. The landlord couldn’t hear a word the man said. The man screamed at him. He called the landlord a prick and a dirty capitalist. Although the landlord didn’t understand the precise words, he understood the gist of the harangue. By now, the man had become adept at reading lips. The landlord called the man a no-good socialist freeloader and tossed him onto the street.

The man lay on the pavement and stared at the sky. He heard the rush of warm air from a vent beside his head. He heard the caw of crows wheeling on the updrafts. He heard the rumble of traffic all around him. But there was one thing the man didn’t hear. He didn’t hear the cries of a woman warning him to look out for the streetcar.