I despise Margaret Atwood. Living as I do in Toronto, such a statement may come off sounding like blasphemy. How can you say such a thing? ask the pious onlookers. It is precisely because I am from Toronto that I despise her.

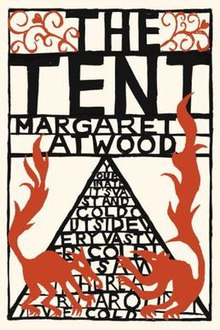

As a high school student in Toronto, they made me read her poetry and novels. The first work I read was Surfacing, Atwood’s first and least satisfying novel, but it was Canadian, and it seemed important to let us kids know that it is possible for a Canadian (& a woman no less) to publish a real novel. Then they made me read Life Before Man & Edible Woman, which, in retrospect, seem odd choices for teenaged boys. I had neither the interest nor the maturity to bother with passages about such things as the complexities of sex after a mastectomy. And so, in university (ironically majoring in English at Atwood’s alma mater), I made a point of avoiding the CanLit courses. Atwood continued to publish, and the novels just got bigger and bigger. I lost patience. I’m not going to sit for hours and read all that, I told myself. So when I saw Atwood’s latest offering, The Tent, and when I saw that it was a slim 155 pages of well-spaced type with a generous helping of illustrations, I decided it was time to reacquaint myself with the divine Ms. A.

I have been duped! I had taken the book’s size in the spirit of a manufacturer’s warranty—it would be an easy breezy read. I was mistaken. What is The Tent? The Tent is not a single, coherent narrative. It is vignettish—polished snippets that appeal to those of us born into the age of the short attention span and the 3-second sound byte.

The first of the book’s 3 sections gives the impression of an Accomplished Writer of a Significant Body of Work who takes a backward glance at her work, her life, a bit wistful, and bit regretful—a bit jaded? She addresses the younger writer. Is the acolyte’s work any good? She isn’t sure anymore. How does one judge such a thing? The old standards don’t seem to help now. I begin to wonder if Ms. Atwood isn’t putting rocks into her pockets and strolling into the Don River. But as I proceed to the 2nd and 3rd chapters, I see that she is up to her old tricks—with psychoanalytic fairy tales, skewed mythologies and cautionary tales masquerading as science fiction.

Is it possible to discern a single thread that might bind together all these snippets? Maybe not. How does one judge such things nowadays? If there is a “theme” in all this, maybe it is the matter of setting things down in words. Consider this passage from the piece which gives the book its title:

The trouble is, your tent is made of paper. Paper won’t keep anything out. You know you must write on the walls, on the paper walls, on the inside of your tent. You must write upside down and backwards, you must cover every available space on the paper with writing. Some of the writing has to describe the howling that’s going on outside, night and day, among the sand dunes and the ice chunks and the ruins and bones and so forth; it must tell the truth about the howling, but this is difficult to do because you can’t see through the paper walls and so you can’t be exact about the truth, and you don’t want to go out there, out into the wilderness, to see exactly for yourself.

Ah, Margaret, you’ve hit the nail on the head. Writing happens inside, where it’s safe (or where we fool ourselves into believing it’s safe). But the writer’s subject, truth, is outside, where it’s dangerous and where the written word may have no currency. Today, the writer’s place in the world is precarious because it is no longer clear that the writer’s words make any difference. No wonder the book opens with such wistfulness. I give this book a resounding 4 stars out of 5—even if I do despise its author.