When I answered the phone, a nondescript male voice asked for mister Winter. I said he was out and asked if the caller cared to leave a message. The nondescript male voice gave a name and said he was calling from Factory Casket Wholesalers. He understood a need had arisen in mister Winter’s household. A need. I assured him no need for a casket had arisen in mister Winter’s household. But he was insistent. I was about to dress down the caller (for what I considered to be an annoying persistence) when he gave my husband’s full name. There aren’t many Archibald Peter Masterson Winters (only one that I know of) so I paused.

That is mister Winter’s full name is it not? (The caller sounded like Perry Mason.) I have the right household do I not?

I agreed that it did seem he had the right household.

Well now look here then. (As if he were doing me a favour!) Let me read you something.

He read quickly so I couldn’t make out everything he said, but the gist was that Mrs. Anne Annabel (don’t ask) Winter nee Summer, late of—, loving wife (ha!) of Archibald Peter Masterson Winter, mother of etc., died suddenly on (today’s date).

What are you reading? (I have to confess there was a teensy bit of hysteria creeping into my voice.)

It’s from today’s obits.

Don’t shit me! (I screamed.)

Madam. His voice was suddenly sober (as opposed to nondescript). I assure you. Those of us who work in the casket industry do not, as you so genteelly put it, shit other people.

At first, I felt I should apologize, but when I considered how he had just advised me of my own death, that seemed to even things out. I promised I would pass along the message then I hung up.

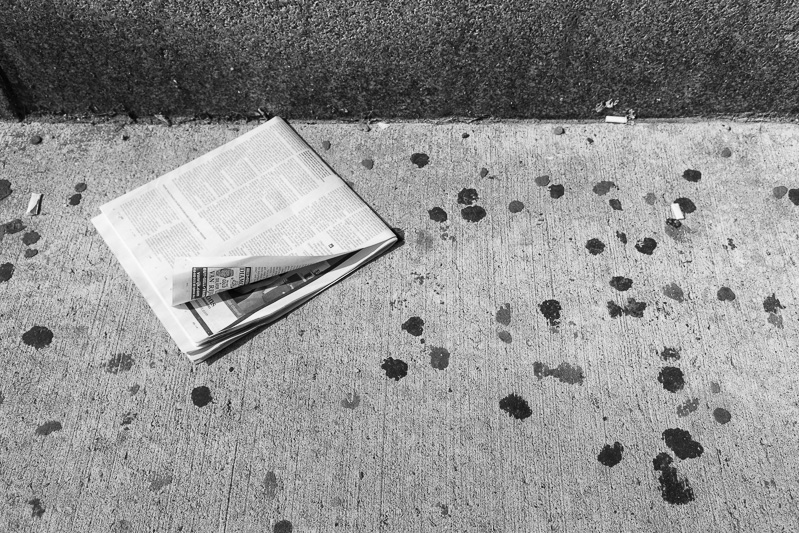

I slammed down my coffee mug and threw off my terry cloth bath robe. Jumping into a pair of jeans and sweat shirt, I tore to the corner to buy a newspaper. Even before I had made it back home, I was thumbing through the paper with pages flapping in the breeze and unthumbed sections tucked under my left arm. There it was: Mrs. Anne Annabel (don’t ask) Winter nee Summer. I was officially deceased.

I was looking for the number of the newspaper’s Obituary Department when the phone rang again. It was my best friend, Monica, who lived a couple streets over. Speaking through choked sobs, she made a slurred request to speak with Archie. Poor Archie. I told her Archie wasn’t in but if she cared to leave a message …

Just tell him I saw the obituary and—I had no idea!—I am so, so sorry. Tell him I’m sorry and if there’s anything I can do—you know—don’t hesitate. Just call me. Got a pen to take down my number?

Monica.

Ya?

It’s me.

Huh? What’s that supposed to mean? “It’s me”?

It’s me. Annie. Your friend.

But Annie’s dead.

No she’s not. I’m right here.

But I was reading the society column this morning and noticed right next to it the obit that says how Annie’s dead.

If Annie’s dead then how can I be talking to you on the phone?

I dunno. Are you sure it’s you?

Oh for chrissake!

The conversation rambled, but by the end of it I had persuaded Monica that if she cared to have a coffee with me in the afternoon, she could drop in without having to dress all in black, which came to her as a relief because all her black outfits were at the dry cleaners and she didn’t know how she could have faced a grieving widower without wearing a black outfit. But a little later I had to cancel, which was fine with Monica because, to be honest, she wasn’t yet comfortable leaving the children alone with her latest nanny.

The reason for my cancellation was a phone call to the newspaper’s Obituary Department. I spoke to a gruff-sounding man named Ken Yakamoto who was more intent upon telling me that Ken was short for Kenji and not for Kenneth than upon helping me to bring about my resurrection. I said I wanted a retraction and apology and didn’t understand how the paper could have printed my Obituary.

Well … He shrugged his shoulders. I couldn’t see him shrug his shoulders since I was talking to him via telephone but I could sense a shoulder shrug in the tone of his voice. We never print these things until we’ve got a notarial copy of the funeral director’s certificate in our hands so I don’t know how we could have made a mistake.

I expected him to ask: are you sure you aren’t dead? But he proved to be a man of restraint. Instead, he had a practical suggestion. While technically what he needed was a notarized letter from a solicitor confirming my existential status, that might take a while and put me to some expense; why not come down in person with a piece of photo-ID? If I hurried I could have the retraction and apology in tomorrow’s paper. So I cancelled my date with Monica and raced downtown instead.

Ken was a middle-aged man though quite fit (certainly moreso than Archie) who sat with perfect posture and wore a simple white cotton jacket over a black T-shirt. As I pulled my driver’s license from my bag Ken rose and shut the door. For privacy (he said). When Ken returned to the desk he apologized for the error. He didn’t know how it could have happened. It was absolutely unacceptable. Unforgivable in fact. He was so ashamed. Things had not been going well at work lately. Little slip-ups here and there. He didn’t know why. HR had spoken to him a couple times and he was afraid this might be it. They might fire him for this one. He had a wife and two young children to support. He needed his job. He needed to fix this latest slip-up. Make it all right.

I assured him it was a minor thing—kind of funny when you thought about it—

No. (The force of his objection nearly knocked me off my chair.) It is not the least bit funny. It is a matter of deep shame to me.

But it can be fixed. No worries.

No. Not fixed. Many worries. There it is. My mistake in print. Do you know what this paper’s circulation is? Millions. And there’s my error. For millions and millions of people to see.

He rose from his chair and for the first time I noticed that what I had taken to be a white cotton jacket was in fact a gi; Ken was dressed for the dojo. He stood formally as if he were about to execute a kata.

I must make this right.

Yes (I agreed).

The truth is important.

Of course it is.

I was held transfixed by the man’s intensity.

That’s why the obituary must be true.

What?

Kenji Yakamoto produced a knife from behind his back and held it high above his head. And in the instant before he lunged, the oddest thought passed through my head: Screw the truth, I thought; why couldn’t this have been the National Enquirer?

Mrs. Anne Annabel Winter nee Summer, late of—, loving wife of Archibald Peter Masterson Winter, mother of etc., died suddenly—.