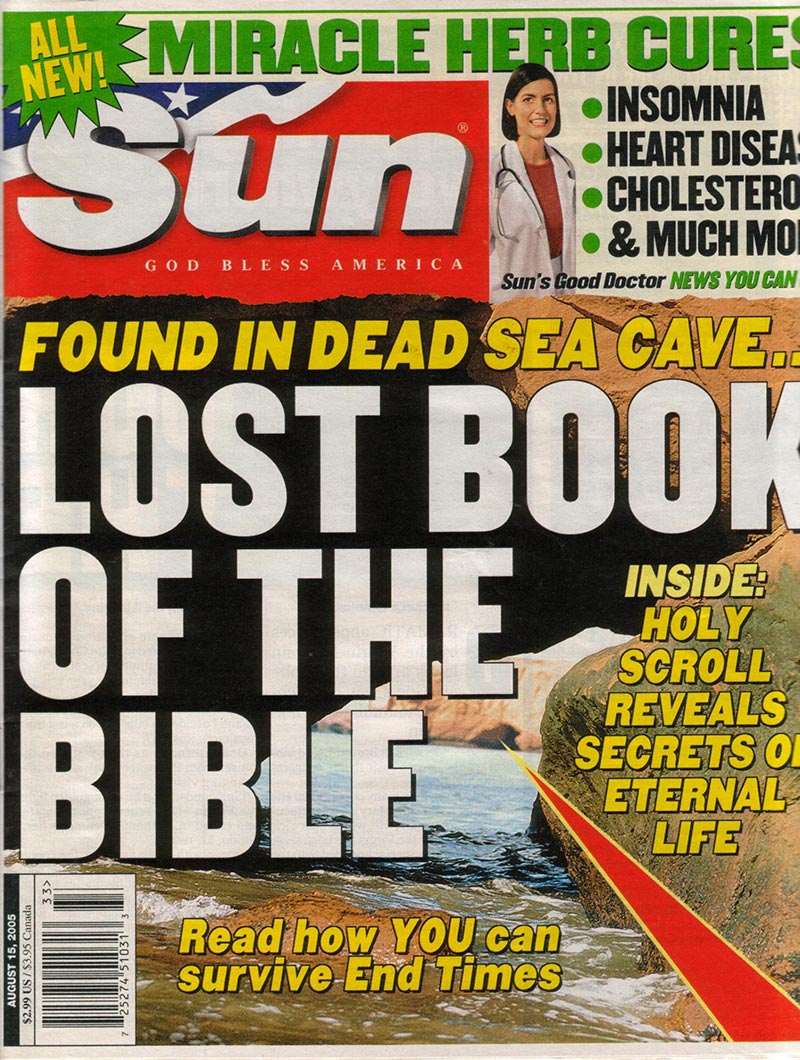

I went to the airport to pick up my in-laws from vacation, and because their flight was delayed, I went to the nearest news stand to find something to read. I couldn’t help but notice the headline for the “Sun: Found in Dead Sea Cave … Lost Book of the Bible”. I laughed and decided I had to have a copy. It promised to reveal the secrets of eternal life and also promised to tell me how I might survive End Times. I wondered if, as a bonus, the magazine would reveal how to overcome cases of logical incoherence.

Magazines like The Sun are a bad news/good news proposition. The bad news is that they run afoul of the great commandment to love god with all one’s mind. It appears that the gift of mind is duly honoured, but only for the purpose of taking money from the gullible. The good news is that the rag betrays an overwhelming affirmation of the spiritual dimension in everyday life. Whatever else one cares to say about its readership, clearly it is a people hungering for assurances of a meaningful and meaning-filled existence.

The story tells of a lost scroll discovered at Qumran which purports to be a second book by the prophet Isaiah. It quotes one Dr. Alan Borndahl, a supervisor of the excavation, who appears to have discovered the text, translated it, and offers up such sophisticated interpretations as:

“Isaiah’s vision includes a description of ”mighty engines, some flying as birds, others crawling like oxcarts, who pursue the enemy without driver or falconer.” Borndahl believes this describes the widespread use of unmanned drones and military robots in combat.”

It should be no surprise that a google search of Alan Borndahl produces no hits. [Update: it does produce hits in relation to The Sun article.]

Some cultural critics are content to dismiss this tripe as mere entertainment, harmless fluff, like navel lint. But it isn’t even entertaining—not when you compare it to a factual account of The Nag Hammadi Library, whose discovery reads in equal measures like an international spy thriller and a story of existentialist absurdity.

Arguably the most important archeological discovery of modern times, the Nag Hammadi find begins its story on May 7, 1945 when a farmer named Ali, while on a job as night watchman for some irrigation equipment, caught and killed an intruder. As an act of blood vengeance, Ali was killed the next morning. Ali’s wife told her seven sons to keep their mattocks sharp. In December, two of the sons were digging for nitrates to fertilize their fields when they uncovered a large clay jar. The one son, Muhammad Ali, overcame his fear that the jar contained a jinn and broke it to discover a collection of ancient books. He wrapped the books in his tunic and carried them on his camel to his home in al-Qasr. A month later, a man named Ahmed fell asleep not far from Muhammad Ali’s home. He was the alleged killer of Muhammad Ali’s father. And so Muhammad and his six brothers set upon Ahmed, hacked him limb from limb, and ate his heart. Although there were no eye witnesses to the event and therefore no charges, nevertheless, Ahmed was the sheriff’s son and so Muhammad Ali’s home was searched on a daily basis. Muhammad Ali decided it would be best to get the ancient books out of his house and so gave them to the local Coptic priest, Basiliys Abd al-Masih. The priest’s brother-in-law, Raghib Andrawus, was an itinerant teacher who stayed with the priest and his wife once each week, and recognizing the value of the books, took one of them to Cairo to show a scholar named George Sobhi who then called the Department of Antiquities which negotiated the purchase of the book for the Coptic Museum. Too bad Raghib took only one book. While he was in Cairo doing the right thing with one volume, the balance of the library was scattered to the four winds.

In one instance, Muhammad Ali’s mother, the widow, believing the books were bad luck, burned one of them in her oven. Illiterate Muslims bought the balance and entrusted them to a gold merchant who sold them piecemeal to, among others, a grain merchant, and a one-eyed bandit (I’m not kidding) named Bahij Ali. A Belgian antiques dealer got most of the books out of the country and his widow ended up selling Codex I to the Jung Institute in Zurich after stops in Ann Arbour and New York. It was not until UNESCO became involved in the 1960’s that all the books were reunited in the Coptic Museum. The first volume of a facsimile edition appeared in 1972 and the first English translation was published in 1977.

The point of this story—or at least the point I’m trying to make—is that it took years before any scholar had access to the Nag Hammadi texts, and it took 32 years for an English translation to appear. Even if a newly discovered book of Isaiah were disseminated using new information technology, it would be years before the first translations appeared. The process would be impeded by all-too-human concerns, like who was the most “expert” translator for the job, who owned the rights to the translation, who would fund the work. Egos would have to be coddled and institutions would vie for glory. The account in the Sun seems too neat, too clean (not enough murder and intrigue and greed) to be plausible.