There’s a traditional view of how a poem relates to the world that has been with us for almost 2,500 years. This view is a reflection of an equally traditional view of how our world is organized. Although we’d like to describe ourselves as up-to-the-minute advanced scientific creatures, this ancient view is still with us in subtle ways.

The view looks like this: our world is organized as a hierarchy. At the top of the hierarchy is a full-on transcendental reality. This is the heightened apprehension of “things as they really are” that we would be able to see if, with Plato, we could crawl out of our caves, or if, with St. Paul, we could let the scales fall from our eyes, or if, with William Blake, we could cleanse the doors of our perception and see the world as it really is—infinite.

But because we live in caves and our eyes are covered in scales and the doors of our perception are murky, the world we inhabit looks ordinary and dull. The table we eat at has a solidity to it, but it’s plain, and the people we jostle on city streets are solid enough, but they aren’t terribly interesting. Ours is the tangible world of everyday life. It is a diminished world. Only on rare occasions does this diminished world crack open and let in some of Leonard Cohen’s light.

And then there is the poem. It is our heroic effort to cope with the diminished circumstances of our real-world living. I say ‘heroic’ because our poems inevitably fail but we write them anyways. They come from the struggles of finite beings who occupy the real world of solid bodies. They are necessarily less than their authors, and so, like their authors, they are a diminishment.

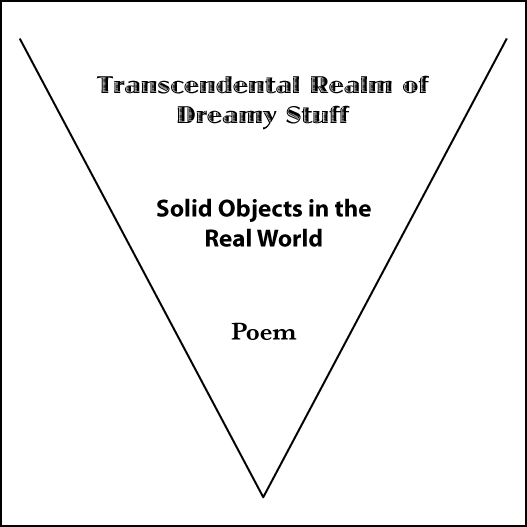

The poem’s value, like that of any art, comes not from anything that inheres in the poem, but from its role as placeholder in a cosmic syllogism: a poem is to the world as the world is to transcendental reality. In its role as placeholder, the poem directs our attention to higher things. The chart below illustrates this relationship. It looks like an inverted pyramid. It shows the conative process in which the wide open reality of “life, the universe, and everything” is reduced to our feeble poetic expressions.

You don’t have to believe this, of course.

There are competing accounts of a poem’s place in the grand scheme of things. One such account is implied by Descartes’ view that the only thing we can know for certain is that we are thinking things. The only verifiable reality is the interior reality of mental processes. That allows us to redraft the chart above. We could say that the transcendental, the solid world, and the poem, are all mental processes called perceptions and therefore all have the same value. Rather than displaying them hierarchically, we can display them as occupying separate unrelated spheres or as occupying a single jumbled sphere called the mind. However we choose to represent them, it’s fair to say that, on this view, the poem is no longer a diminishment of anything. It is the traces of a mental reality, and while not real in itself, a poem is no less real than a rock, say, or a soul, because they aren’t real either.

Another account of a poem’s place in the world comes from science. When I speak of science, I speak of a materialistic discipline that tries to describe phenomena. If I were to place science on the diagram above, I would place it in the middle among the “Solid Objects in the Real World.” It would treat the “Transcendental Realm of Dreamy Stuff” as phenomena that have simply been misdescribed and properly belong among the “Solid Objects.” And a poem is simply a misguided attempt at explaining phenomena—like a bad theory or speculation over a pitcher of beer.

The problem with these alternate accounts is that poems have a nasty habit of leaping outside their own words and becoming objects in their own right. Poems are like trick balloons that want to rise outside themselves and float through “Solid Objects in the Real World” and on up to the “Transcendental Realm of Dreamy Stuff.” Poems don’t know their proper place.

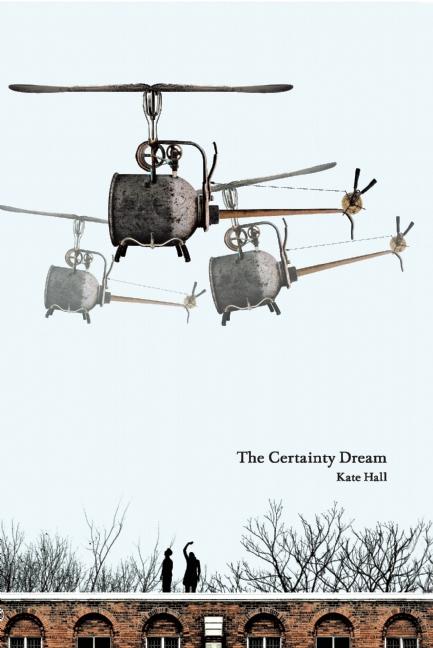

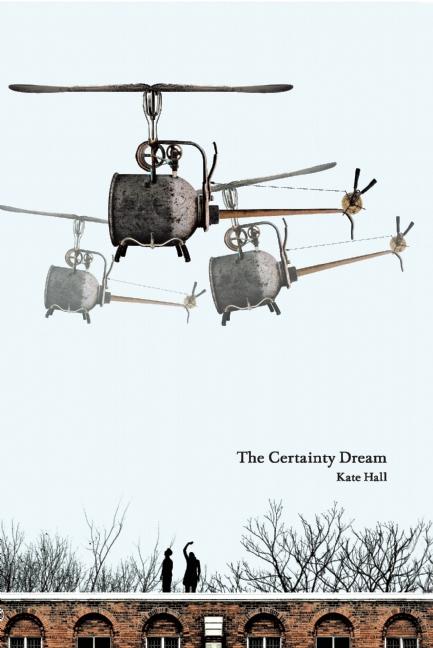

This is rather a long introduction to a review of poetry but, what the hell, it’s my blog and I’ll do as I please. What I hope my introduction has done is to map out some of the terrain that Kate Hall explores in her first collection, The Certainty Dream. It is a terrain shared by philosophers, especially epistemologists, people who investigate what it is we can claim to know for a certainty. As the title to Hall’s collection suggests, she is playing with classic questions about perception, consciousness and knowing. She doesn’t behave like a philosopher because she doesn’t stake any ground. She doesn’t claim to be a Cartesian or an advocate of science. She’s a poet and so can leave claims unstaked.

When most poets gather up their poems from scattered publications to produce a single volume, the result often looks like a scattered gathering of poems. Hall’s collection is remarkable for appearing to proceed in the opposite direction, as if all the poems were written first for a single coherent work, then bits were carved off and sent away to appear in journals. As a result, there are some clear threads that run through nearly every poem to give the collection a tautness. Dominant images include:

• containers

• vehicles

• miniatures

• birds (especially mynah birds but also blackbirds and crows)

• recursion and paradox (e.g. people swallowing themselves)

Containers

There are bathtubs, ponds and dinghies, a basin and a submarine, body bags and sarcophagi, skin, a petri dish, houses, moving boxes, a “bomb-proof concrete room/with twelve locks on the door”, a pear grown inside a bottle, “the old blue steamer trunk”, suitcases, the belly, a “giant domed ceiling”, cups, a vat, a jewellery box, a glass box, and a “shapely hole.” In a poem titled “The Shipping Container” Hall notes that “It’s true, the container / has great aesthetic value but I was really hoping / for a free watch with a rechargeable battery or / at least a better kind of nothingness.” This raises a question about poems. Are they containers for meaning? Do they have an aesthetic consequence apart from their contents? Or, to put these questions in terms of the diagram I created above, do poems rise up from their diminished status to a position of substance in their own right? Can words jumbled together, become something greater than the sum of their parts, like Ezekial’s dry bones waiting for breath?

Vehicles

Containers can be vehicles too. A container can hold information, but a container that moves can also transmit information. And so we encounter living bodies and bathtub races and trains, model boats and elephants, the Mars rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, toy dump trucks, a blue minivan and ships burning in the harbour. We see a clear correlation between vehicles and the transmission of information. For example, in “The Sun Library”: “The 11:40 train departs, / arrives 16:17. All the time / I’m travelling, I’m at a loss / for information.” And in “Remind me what the light is for” we have a brilliant encapsulation of the state of poetry in 2010:

Dear occupants of the moving boxes,

there are days when I forget

you have to live here too, in cardboard

cubes, tossed inside with lamps

that do not work. Everything is labelled but

because we’ve reused the boxes, the objects listed

are not what’s inside. So, occupants, I am losing

faith.

People have lost their faith in poetry too. Although we sometimes use poems like containers to convey information, the information that they convey is about as useful as lamps that don’t work. And the forms we learned in school are like mislabeled boxes. If “[t]he mysteries are in need of / continual rephrasing” but we allow the mysteries to ossify in a tired curriculum and worn-out scripture, then of course people will lose their faith.

In another “container” image, Hall draws on Richard Dawkins: “Evolution is about the genes / manipulating the bodies they ride in.” Is that what a poem is? A body that carries coded information? Or, in the end, is a decoding simply impossible? As her book comes to a close, Hall writes: “I imagine myself / at an art gallery looking at installations / and not pretending there can be / any sort of understanding.”

Miniatures

Many of the poems feature small things. The world is shrinking. “You must have gotten smaller to fit yourself / into that space.” There are birds “whom I forced into a small fragmented area”. “It’s scary to loom this large in / the world of tiny experiences.” She writes of “shrinking the sarcophagus / until it’s the size of a small jewellery box.”

Is poetry an act of diminishment? If you use poetry to convey decipherable meanings, do you sacrifice something as you squish those meanings into their tiny containers? Or can we break poetry out of that old hierarchical model that treats it as an inferior kind of knowing?

Birds

I’m not sure what to make of the birds. Crows are traditionally seen as symbols of death or desolation or loneliness. But here, the primary bird is the mynah bird. Maybe the birds here are like mislabeled boxes. Whatever they might be will only reveal itself by watching them in their own habitat. Or maybe it’s a pointless exercise. As Hall says in the poem which gives the book its title: “Certainty could be folded / into a featherless bird.” This echoes Hall’s “Dream in which I apologize to the birds” “those whom I made / strings of words / featherless”. If we try too hard to nail down a meaning that we can affix to the bird, we’ll end up stripping the bird of the very thing it needs to be a bird.

Or maybe the bird is a shape-shifter. In “Dressed-up Dream”:

mynah morphs into crow

stands for nightingale

don’t assume abandonment

he needs a new name

not being himself anymore

and builds a nest from anything that’s available. At other times, the mynah has its tongue clipped. And at the end “this became the dream his dream in which I did not allow him to speak / and the dream in which I imagined him speechless before me”.

A bird capable of speech that is rendered speechless? Maybe that’s like a poem capable of being a container that transmits information. Maybe there’s nothing to understand in a poem any more than there’s something to understand in the speech of a mynah bird. A bird simply is. In the same way, maybe a poem must be left to be whatever a poem may be.

Recursion and paradox

The poems are riddled with recursive images that drag us into paradoxical games. Given Hall’s preoccupation with consciousness, I don’t think this is such an arcane thing. After all, consciousness is a recursive and paradoxical phenomenon. We are all beings who are aware of ourselves as beings who are aware of ourselves. In “Dream in which the dream is scaled to size”, “you are about to swallow / the whole world with you / in it”. This is an image which appears several times.

In “Overnight a horse appeared” she presents an interesting variation by imagining herself crawling back inside herself. The “she” doing this imagining is probably the poem itself as a kind of reified character: the poem is the character who is the subject matter of the poem. The poem warns us of itself. It’s a Trojan horse. If we fall prey to its ruse, who knows what damage it will do. “For my horse and me, / it hardly matters. Though it will matter for you: / how you decide to read me or / whether you do.” The ruse is to trick me into believing the poem is meaningful. The paradox is that if I discover that the poem is a ruse, then it will have becoming meaningful and will have succeeded in tricking me despite the fact that it failed to trick me.

Then there are the mynah birds who “pluck / themselves out of existence.” Maybe this engages us in a similar paradox: the poem succeeds when it disappears.

Kate Hall’s The Certainty Dream is fun and interesting and challenging. I sense in it—and this is an entirely personal sense—a quiet yearning to create more poetry in which the self-conscious poet grows still. The “mynah dreams himself into a statue”. When that happens: “who will call out / and calling out who will answer”.

Perhaps these are questions which should remain unanswered, or simply answered by the fact of more poetry.