This book is subtitled “Ars Poetica in 59 Versos” which is a play on the word versos, suggesting both the verses of a poem and the left hand page (as opposed to recto, the right hand page) of a two page spread in a book. Dionne Brand imagines that the author is attended by a clerical figure, the blue clerk, who manages the author’s versos, all her left-handed writing. She gathers them in bales in a warehouse on a pier. One can imagine her filling shipping containers then loading them onto giant ocean-going vessels. Brand never precisely characterizes the versos because, paradoxically, what she offers us is the recto, the polished and the published, as an accounting of the versos. She operates by implication. We must imagine for ourselves what pages she crams into these bales. Are these the mediocre? The banal? The half baked?

Another thing to note about the subtitle is that, while it claims there are 59 versos, there aren’t. Maybe this is false advertising. Maybe Brand is numerically challenged. Damn it, Jim, she’s a poet, not a mathematician. Sometimes she gives her verses (as opposed to her versos) precision headings—Verso 13, Verso 13.1, Verso 13.1.1—like she’s Ludwig Wittgenstein offering us her version of the Tractatus Logico Philosophicus. But along the way, great swaths of numbers go missing. Had she published all 59 versos complete, her book would have run to a thousand pages or more. Presumably these others are the left-handed versos, the ones that never made it into the final draft. Brand self-censored or, to follow the narrative, the blue clerk intervened, hauling away the rough bits to her compacter to produce another bale for her shipping container.

Another way of thinking about the narrative is to treat it as a neurological drama: the author (recto) and the blue clerk (verso) are metaphorical ways of reflecting the bicameral structure of the human brain. There is speculation that this neurological quirk is responsible for everything from imaginary friends in childhood, to the habit of talking to ourselves, to the perception of ghosts, to the belief in God(s). Each hemisphere of the brain mirrors itself to the other and, together, they carry on a lifelong dialog. Alongside this is the theory of hemisphere dominance. The right side (recto) is intuitive, creative, artistic. The left side (verso) is rational, methodical, pragmatic. For any given individual, one side tends to prevail over the other. While it’s not obvious on its face that the author and blue clerk adhere strictly to these differences, one wonders. And which has the final word?

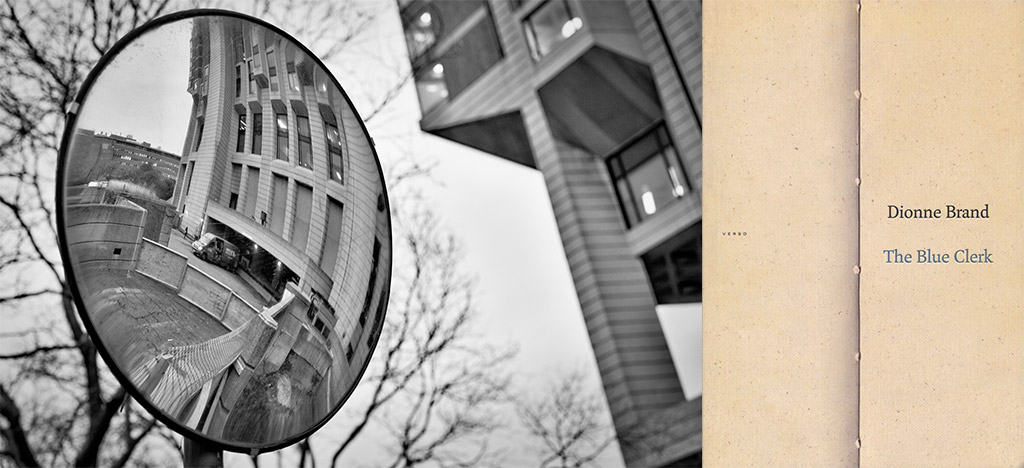

There is much I could write about this book but I shall consign most of it to my own blue clerk and mention only one thing of a personal nature. I think it’s only natural that we pay more attention or are more excited by words that speak directly to our personal experience. In this instance, my attention was piqued by a reference early on to Borges and his memory of his grandfather’s library. It called to mind his short story “The Library of Babel” about a library which, while not infinite, is nevertheless vast enough to hold a record of all human thought. Borges has a fascination for libraries. By chance, while I was part way through the anthology in which this story appears, I passed the Robarts Library and took a photograph of it. The collision of Borges and the Robarts Library spawned a reflection which I posted in March of 2018. It is a natural law: if you live in Toronto and you read Borges, then you must think of Robarts Library. Sure enough, in Verso 28, Brand writes:

The ground smelled like fresh ploughed earth outside the Robarts Library and the clerk thought of the books inside and how, collected there in the stacks, they have returned to their original selves as trees and earth, and how difficult it must be for them to be wrenched open again and again to be read and read even as they are returning, reaching through each other and the concrete boat around them. That is why it smells like new ploughed ground around the library.

Somehow Brand shares my tendency to associate Borges with the Robarts Library.

In a move I ascribe to the folly of youth, I once attended law school. While I was there, they started to renovate the Bora Laskin Law Library, so they moved the entire collection to the 13th floor of the Robarts Library. Being a left-brained institution, they do not believe it is unlucky to have a 13th floor, and yet they compelled me to spend a year on that 13th floor so, says my right-brained self, there must be something to that superstition. I recall it as a continuous incarceration within a Brutalist soul-deadening concrete abomination. I don’t remember going home at night nor arriving the next morning. I remember only that I read. I read until I couldn’t keep my eyes open anymore. Sometimes I woke to find myself slumped over my books. Other times, to amuse myself, I wandered into a stairwell and dropped pennies down the depthless hexagonal shaft.

Robarts Library is a behemoth that tries to swallow all human written output. Like Google, it aspires to a total knowledge. Necessarily, it must function more like the blue clerk in her warehouse than a snooty curator at a fine arts establishment. It doesn’t discriminate; it accumulates. Once, while wandering through the stacks, I stumbled on a copy of Crad Kilodney’s Lightning Struck My Dick, so I know I’m right in my assessment: Robarts serves the verso more than the recto.

In my earlier reflection on Borges and the Robarts Library, I drew a comparison to photography, surmising that it must be possible to create the visual equivalent of a Library of Babel, a collection of all possible photographs. In the age of digital photography, it is easy to calculate the total number of such images: it is the product of all the pixels in an image and the bit-depth of each pixel. So, for example, the number of all possible 50 MP RGB images is 5 x 107 x 224. It is a large number, but not infinite.

The Blue Clerk offers an analogous correspondence between the written and the visual. Every photographer must have a blue clerk who manages the bales of versos. This is especially true of photographers who produce photo books where each spread comprises a verso and a recto. How do we characterize those versos? Do we make them disappear yet make their presence felt by inference? How do we accomplish this? Or is this just something we do as a matter of course, like an involuntary throat-clearing before we speak? Here are some photographs, we say, and I made them over the course of a year in which I discarded thousands.