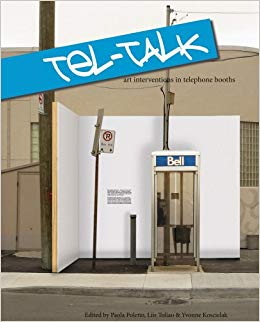

The 8th installment of my January Book Project is Tel-Talk, edited by Paola Poletto, Liis Toliao & Yvonne Koscielak – published by Tightrope Books. It both documents and responds to interventions/installations staged last year around telephone booths mostly in downtown Toronto, mostly near where I live, which makes it personally a fun book to read. There’s an almost elegiac undertone to the book: it’s time to say farewell to a cultural institution which the march of technological change has rendered obsolete. In that regard, the payphone has become emblematic—almost a totem—of something fundamental about contemporary life.

The institution at stake here is not simply a technology. The shift from phone booth to cell phone marks a shift in the way we describe the public/private distinction. Phone booths once offered us a measure of discretion in what we regarded as an intimate act—the private conversation. But cell phones have eroded the expectation of privacy. Now, I don’t think there’s anybody who hasn’t overheard one half of a conversation that was one half too much. On a cell phone, it’s all-too-easy to enclose ourselves in a psychic bubble of privacy, oblivious of the fact that we are projecting our voice into a public space. Kind of like blogging, I guess. And without the privacy of phone booths, where will Superman change? Behind a bush in a public park? And how will he avoid getting charged with public indecency?

Following close upon the Occupy Movement’s 2011 demonstrations, Tel-Talk is keenly aware of the way the payphone embodies the uneasy relationship between corporate power and private vulnerability. The phone booths are owned by Bell Canada, in turn owned by BCE Inc. which ranks 263 on the Forbes Global 2000 list for 2012. Yet the booths remain for the benefit of those who, for the most part, cannot afford cell phones and the data plains they require. The booths are gritty, often covered in graffiti, almost organic in they way they merge with their environment. In other words, their devolving appearance suggests the opposite of global corporate power.

This grittiness plays itself out in the contributions. We get noirish excerpts from Barry Callaghan. Excerpts from Cathi Bond’s forthcoming novel, Night Town, which evoke Toronto in the 70’s. A narrative poem, “Aspirations”, by Liz Worth that follows suburban girls downtown for a night of stupid. In “We Understand Each Other On A Cellular Level”, Jessica Westhead records half-conversations overhead at the intersection of College and University. Hal Niedzvieki’s “Ossington and Dundas” imagines a string of conversations running through a single phone booth. I want to pause here at Niedzvieki”s piece to contemplate two spelling mistakes that leave me scratching my head. The first is the word “doing” which appears as “dong”. The second happens on the following page with the word Ossington which appears as “Ossingtoin”. It’s as if the “i” didn’t like where it was and decided to up and move. If it’s accidental, it’s one of those serendipitous mistakes that adds more than it subtracts. I’d like to think it was deliberate.

I close by settling on the final sentence of Ryan Bigge’s “Four Short Calls”: “We can talk anytime, with nearly anyone, but our voices now originate from nowhere in particular.” It is a statement reminiscent of observations by writers like Pico Iyer and Geoff Dyer on the placelessness of globalism. Pay phones reflect the cultural rootedness of an earlier time, and their disappearance foretells a loss far greater than the obsolescence of a technology or the sacrifice of personal privacy.

See the Tel-talk blog. Hope it keeps going.