In yesterday’s post on Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, I asked a question which I never answered: “And can we make anything more of it [the Tropic of Cancer] 75 years after its publication?” That’s a question about Miller’s legacy. Perhaps more than any other author, Miller’s worked carved out a space in American writing for the daring voices of the sexual revolution and its aftermath in the post-AIDS world.

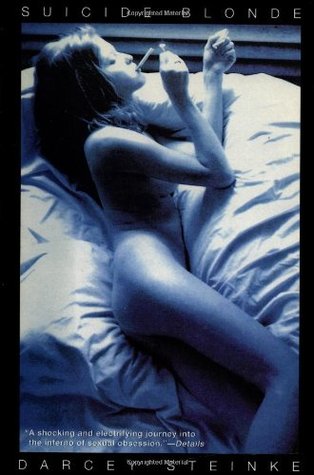

One of those daring voices belongs to Darcey Steinke whose best-known novel is Suicide Blonde. While it is arguable that Suicide Blonde is not a post-AIDS novel (AIDS gets a single mention), nevertheless it is set in the heart of San Francisco in the late 80’s and takes us to gay clubs, whorehouses, parties and tells a story of sexual self-destruction.

Jesse is a 29 year old woman in a relationship with a man named Bell, but Bell has come unhinged by a wedding invitation; a lover from his teens, a man named Kevin, has decided to marry straight. Jesse’s attempts to pull Bell back into their relationship (e.g. dying her hair blonde, having sex with him while someone else watches) are complicated by her own sexual ambiguity. Drawn to the more dominant Madison, Jesse takes a job bartending at the strip club/whorehouse which Madison manages. Inevitably, Jesse starts turning tricks. The whole movement of the novel is an inexorable drift to Kevin’s wedding. Jesse drives down to L.A. and, in a drunken haze, confronts Kevin with the fact that Bell still loves him. And … well … if you like pleasant romps with happy endings, there’s always Danielle Steele.

Steinke writes with a terse prose that has a tough, noirish feel. So we get paragraphs like this:

“Bell turned up Jones and I realized he was walking toward the theater for his audition. I followed. He didn’t seem particularly nervous or troubled, though on Sutter and Jones he stopped for a moment, sunk his hands into his pockets, leaned back against a brick wall and looked up into the sky. His leisurely motions reminded me of dreams … watching your lover speak in hushed tones with someone else. Bell put his flattened hand against his chest. Could he be thinking of the morning his father died?”

Like Miller, Steinke is sexually frank (watching as Madison fists a man until she’s in up to the elbow) and just a little bit blasphemous (taking the idea of a personal relationship with Jesus to its logical conclusion).

More importantly, Steinke shares what I have called Miller’s Gnosticism which rejects the orthodoxy of dualism (with its preference for the mind) in favour of an integrated mind/body whole. Ideas and sexuality belong together. So do religion and violence. At the very least, sexuality and violence need to be reintroduced into our understanding of what it means to be fully human. We see Jesse struggling with this:

“I wondered if the function of my body might be different from the function of my mind. I sensed the peace one found if they subverted either mind over body like a monk, or body over mind like a whore. You could hold both only if they were separated and severely so, like the right and left brain when the fissure is broken in surgery. I was trying by trusting my animal instincts over my intellectual ones.”

This Gnosticism leads inevitably to an aesthetic of shit because it has to incorporate the unpleasant and the vulgar. People vomit, get beaten up, bleed, shoot up, smell, piss themselves. Jesse begins the story of her first time with: “I rode the bus down to Georgia. It smelled horrible, because an old lady in the back had shit in her pants …” Like Miller, Steinke’s characters scorn that “true-love bullshit.” Madison’s ex-lover, the fat matronly woman named Pig, tells Jesse “that horror is everywhere, it’s the rule, not the exception. Life is a disease.”

And finally, as with Miller, the particular messes of this particular story ripple outward with universal consequences—or at least consequences for the idea of America (which, according to some Americans, amounts to the same thing as universal):

“I am the worst kind of person, attractive, overeducated, raised with middle-class delusions of grandeur. But it’s not just me; family life in America sucks, because if you’re even a bit smart, the pressure from your family to jump classes is excruciating. There’s this insane idea that materialism creates status. Even if you make some headway, it’s an internal jump. You’re always middle-class, talking on your cellular phone with your color TV muted.”

The nicest guys she meets are on TV (although, as she acknowledges, being nice is just a cover for weakness). And Madison accuses Jesse of wanting her life to be like the movies. Driving into Monterey on the way to the wedding, Jesse notes all the fast food chains and observes that “like everywhere else in America that was special, it had been spoiled by gentrification.”

America is founded on a dualism—or at least an aesthetic dualism—that is so preoccupied with its head that it’s incapable of acknowledging its body, along with all the messiness that having a body entails.