Not long ago, I found myself standing on the curb of the Champs Élysées being an annoying tourist. I had a big honking camera (Canon Mark III) hanging from my neck which made me the opposite of inconspicuous, and I was doing what I always do when I have a big honking camera hanging from my neck. I was looking for a shot. Actually, I was looking for THE shot. In one of the most photographed places in the world, I was looking for something different. Something that would reflect my unique personal vision. Or … [stick your favourite cliché here _______ ]. Two big black cars pulled to the curb where I was standing. A professional-looking woman got out of the first car and went to the rear door of the second car which she opened while an older gentleman got out. Meanwhile, a handler got out of the first car and came around to my side where he stood in front of me. He looked like one of those computer generated goons from The Matrix who wears an earpiece and is itching to lecture you about how you’re not really human; you’re just a virus. The handler saw my camera and waved a finger at me: no, no, no. I smiled and nodded to indicate that I understood.

What, I wondered, could be so important that a French celebrity, complete with security detail, would pull up right in front of me and hop out of his car. The older gentleman ducked past me and into the Marks & Spencer. You’re fucking kidding me, I thought. All this so he can what? Buy a fresh pair of underwear?

The next day, I found myself standing on a different curb. It was within walking distance of the Étoile Charles de Gaulle or whatever, busy urban Paris, but a little bit away from the touristy streets. Again, I had a big honking camera around my neck, and again I was looking for a shot. I was bored. I was waiting for my wife who had gone into a drug store to buy toothpaste or something. I can’t remember what.

I was mesmerized by the motocyclettes. It strikes me as a great way to get around in the city and I remember wondering why it’s never really caught on in my hometown—Toronto. It’s more than just a mode of transportation. It’s a lifestyle. All these young guys with their scarves and their cigarettes. I thought I was in a Parisian cartoon. I decided to catch them flying up the road. I braced myself against a pole and clicked away until a Citroën pulled up across from me. A man rolled down his window and started yelling at me. With all the traffic, it was noisy and I couldn’t make out exactly what he was yelling, but it was pretty clear he didn’t like my camera. The light changed and the cars behind him started to honk, so he took off in a huff.

It struck me that there was something going on that I didn’t understand—not an unusual situation for me, even when I’m walking around my hometown. When I got back to my hotel room (with its complimentary wifi) I searched “street photography Paris laws” and discovered that France has some of the most stringent privacy laws in the world. This is enshrined in Article 9 of its civil code. And while it may have originally been enacted to curtail the more intrusive behaviour of aggressive paparazzi, it has had a chilling effect on street photography generally. The indignation of celebrities has been adopted by ordinary citizens. In the case of the gentleman driving the Citroën, he expressed his anger notwithstanding the fact that I was shooting in a public place and, more remarkably, didn’t even have the man in my frame; I was pointing my camera away from him. Maybe he was yelling at me on principle. Maybe he was protecting the interests of his fellow citizens.

The best advice I could get via my duckduckgo search was that it’s okay to shoot photos in places where no one has a reasonable expectation of privacy e.g. the Eiffel Tower, the Champs Élysées, along the Seine, etc. But, as my encounter with the handler illustrated, even that is iffy. And what counts as “public” and as “a reasonable expectation” appear to be quite different in Paris than, say, in Toronto. The legislation itself may be effecting a shift in perception that gives plasticity to the very concerns it aims to codify.

What bothers me here is not the rising paranoia that presents as a concern for privacy so much as the way in which the French legislature has chosen to frame the issue. Privacy is a proprietary interest. A person owns their image. The same logic applies to buildings. The owner of a building has the right to suppress a photograph of the building, not because the photograph is an invasion of privacy, but because photography is a species of theft.

I wonder if maybe the French have torn a page from the American playbook that Noami Klein has meticulously documented in her book, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. The disaster (a crisis in personal privacy) summons capitalism to the rescue by converting the “right to privacy” and related “droit à l’image” into commodities. However, like all such transactions, these come with externalities. Here, the unaccounted cost is neatly summarized by France’s minister of culture, Aurélie Filippetti, quoted in the New York Times:

“Without them [street photographers], our society doesn’t have a face,” she said. “Because of this law, we run the risk of losing our memory. This is even more unacceptable when you consider what’s going on online, where millions of images circulate without us knowing how they were taken and in what circumstances. Just to think that Cartier-Bresson or Josef Koudelka would have been prevented from doing their work is unbearable.”

By framing these rights in proprietary terms, the outcomes start to look a lot like those we’ve witnessed with the rise of a more stringent copyright regime. A chilling effect all but eliminates the kinds of “borrowing” and “quotation” that still fall under the fair use and educational exemptions of the Copyright Act. However, with the increased commodification of text and a heightened culture of litigiousness, ordinary citizens are forced out of traditional cultural conversations and only the deep pockets get to play. The same appears to hold true of photography in France. Rather than risk expensive litigation over the meaning of vaguely defined conceptions of privacy, ordinary individuals don’t bother taking photos any more.

Fortunately, Article 9 is limited to France, and unlike copyright laws, there are no international treaties to give its privacy regime a grasp beyond its borders. However, it wouldn’t surprise me if, in the next decade or so, that changes and we end up with some kind of UN-sponsored globally enforceable treaty of privacy rights delivered to us on the wings of paranoia.

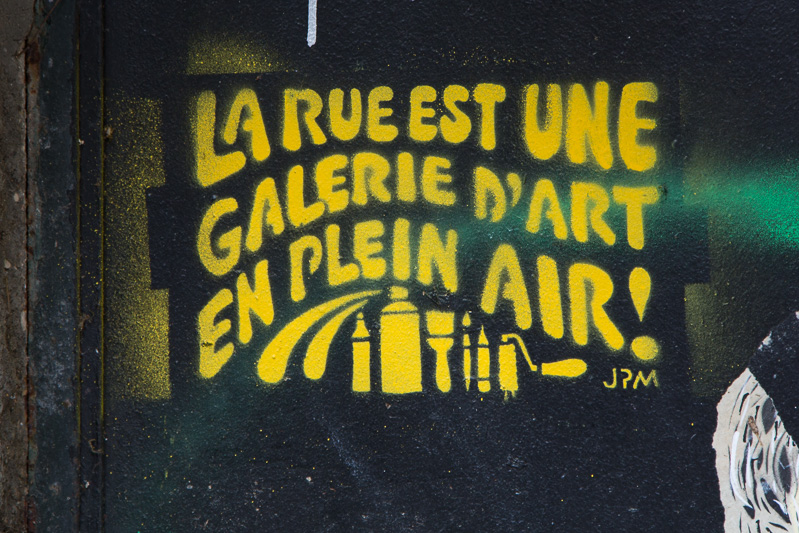

Until that happens, here are some street photos from Paris. Enjoy them while you can.