Although the following is a chapter from a novel-in-progress titled Life In The Margins, nevertheless it stands on its own as a short story. So I offer it as a sample of things to come. If you’d rather not read it on a computer screen, I also offer it as a pdf, epub or mobi file so you can load it on your favourite mobile device and enjoy it at the beach. Be sure to social distance while you read. And use an spf 45 sunblock!

An Elementary Solution To Fermat’s Last Theorem

Once upon a time there was an extraordinary mathematician named Barnabas Moynahan, much admired throughout the land for the many wondrous proofs he had developed early in his career. One day, while scrubbing his genitalia in the shower, their general shape and texture suggested to him an elementary solution to Fermat’s Last Theorem. Although a proof had already been discovered, it was a complex proof using contemporary mathematical tools that would not have been available to Fermat in the seventeenth century. On his death bed, Fermat himself had hinted in his own marginalia that the problem had an elegant and (one assumes) elementary solution. However, such a solution had eluded mathematicians for three and a half centuries until Barnabas Moynahan leapt from his shower shouting: “I have found it! I have found it!” which, in ordinary speech, translates roughly as “Eureka! Eureka!”

Moynahan’s wife was still asleep when this happened, so he left a note for her on the kitchen table: My dearest Myrna, I have found an elementary solution to Fermat’s Last Theorem. Have gone for a long walk to sort it all out in my head before I put pen to paper. B.M.

Barnabas set out in an easterly direction, and after walking for some time in an easterly direction, he turned left and began to walk in a northerly direction, and after walking for some time in a northerly direction, he turned left again and began to walk in a westerly direction, and after walking for some time in a westerly direction, he passed a copse where he heard rustling and there appeared from the copse a large and grunting man-boy whom Barnabas recognized as Nathan, the village idiot. Barnabas was always so wrapped up in his numbers that he never had words for Nathan but merely nodded and passed on by. Nathan, who was not half so dull as everyone assumed, thought the mathematician arrogant and resented his callous treatment. As Barnabas continued on his westerly course, he heard a whizzing through the air and a rock struck him in the head.

Who knows how long Barnabas lay upon the ground before a passer-by discovered him and called for an ambulance. From the emergency ward, he was whisked into an operating room where a neurosurgeon relieved the pressure on his brain caused by a subdural haematoma and removed fragments of the skull from the inferior frontal gyrus. After five hours of emergency surgery, Barnabas lay in the recovery room while his tearful wife held his hand and whispered encouragement through the bandages. When he had stabilized, they moved him to a bed in the intensive care unit where he remained for another five days until his condition was downgraded to serious and he could be transferred to a regular ward. Every day, his wife, Myrna, spent hours at his side, chatting with him, reading to him, quizzing him about the note he had left on the kitchen table. An elementary solution? Really? She knew he couldn’t hear him, but she chatted anyways. If nothing else, it helped her to cope.

Lydia, the night nurse, disagreed with Myrna’s assertion that her husband couldn’t hear her. Nurse Lydia was a young woman of great faith in the healing sciences who believed with fervour that her comatose patients understood more than they were capable of acknowledging. There were apocryphal tales of patients who, following a miraculous recovery, disinherited their heirs for maligning them while they lay unconscious but very much aware, and of patients who, upon waking, recalled to their astonished doctors entire conversations that had been conducted at the bedside while the patient was presumed to have been incompetent. Nurse Lydia said it was best to err on the side of caution, but even if the patient could not understand the words, they might still understand their tone or at least perceive them as a comfort, in the same way that a dog loves to hear the master’s voice even though it can’t understand the words.

The surgeon advised the patient’s wife that the Broca centre of the brain had been damaged, that when the patient woke up, he might not be able to speak, or he might be aphasic, which meant he would be able to speak, but unable to make himself understood. The patient’s wife asked if the math centre of her husband’s brain had been affected, and while the surgeon said, no, he cautioned that her husband might nevertheless experience difficulty writing out solutions. Nurse Lydia had overheard the conversation, and when the surgeon left, she approached the patient’s wife. Nurse Lydia was an amateur math nerd. After her nightly shift, she often went home to pore over math problems. The patient’s wife thought: “What a sad girl” but kept that thought to herself, instead, telling the girl that her husband was a mathematical genius who, before he went on his fateful walk, wrote a note saying he had discovered an elementary solution to Fermat’s Last Theorem. Nurse Lydia was impressed. After the patient’s wife had gone home, and after Nurse Lydia had finished her rounds, she stepped into the patient’s room and sat beside him, holding his hand in hers and gazing at his profile and telling him about all the mathematical problems that eluded her, and about all her efforts to solve those mathematical problems.

Barnabas Moynahan woke from his coma. Nurse Lydia was the only person to witness the moment. She was standing at the foot of his bed and was staring at his eyes when they flickered open. Everyone important had gone home for the day, so Nurse Lydia had no one to tell. The unexpected appearance of the patient’s eyeballs made her start much as she expected she might start if she saw a ghost or a headless horseman. When she recovered her composure, she said hello. The patient didn’t answer but merely stared at her. As she moved around the bed, the eyeballs followed her.[1] Apart from the eyeballs and eyelids, nothing moved. Nurse Lydia asked the patient to wiggle his toes, but nothing happened. She asked him to wiggle his little finger but again nothing happened. She asked him to say something but he merely stared at her with what she imagined to be pleading eyes. Nurse Lydia stared back at the eyes, wondering what to do next. She had read stories and seen movies of people paralysed who blinked or winked to communicate, but what did they use? Morse code? Or a five-by-five grid?

— Mr. Moynahan. She spoke in her most officious and nursely voice.

Mr. Moynahan lay still and blinked at the ceiling. In the next bed a woman who had suffered a stroke and last week was declared mentally incompetent let out a grand sigh.

— Mr. Moynahan, if you can understand me, blink twice.

The eyelids fluttered, but was it enough to qualify as a blink? How far did an eyelid have to move and how decisively? Nurse Lydia wanted fervently to believe not only that her patient was conscious, but also that he was capable of communication. And she wanted fervently for it to be her who made the first contact, who established the link between the patient’s trapped mind and the wider world. If she could do this, then that would make her an agent of freedom. She could stand shoulder to shoulder with other agents of freedom, like Nelson Mandela and Che Guevera and Anne whatshername who worked with the deafblind bitch. People would write books about her and Hollywood would option her story for a film by Martin Scorsese. They’d call it: The Miracle Worker, Part II or maybe The Butterfly and The Bell Jar. She would quit her nursing job and go on the lecture circuit where she would tell her account of extraordinary compassion in the face of a cold and mechanized health care system. Nurse Lydia checked the catheter bag, and seeing that it was almost full, replaced it.

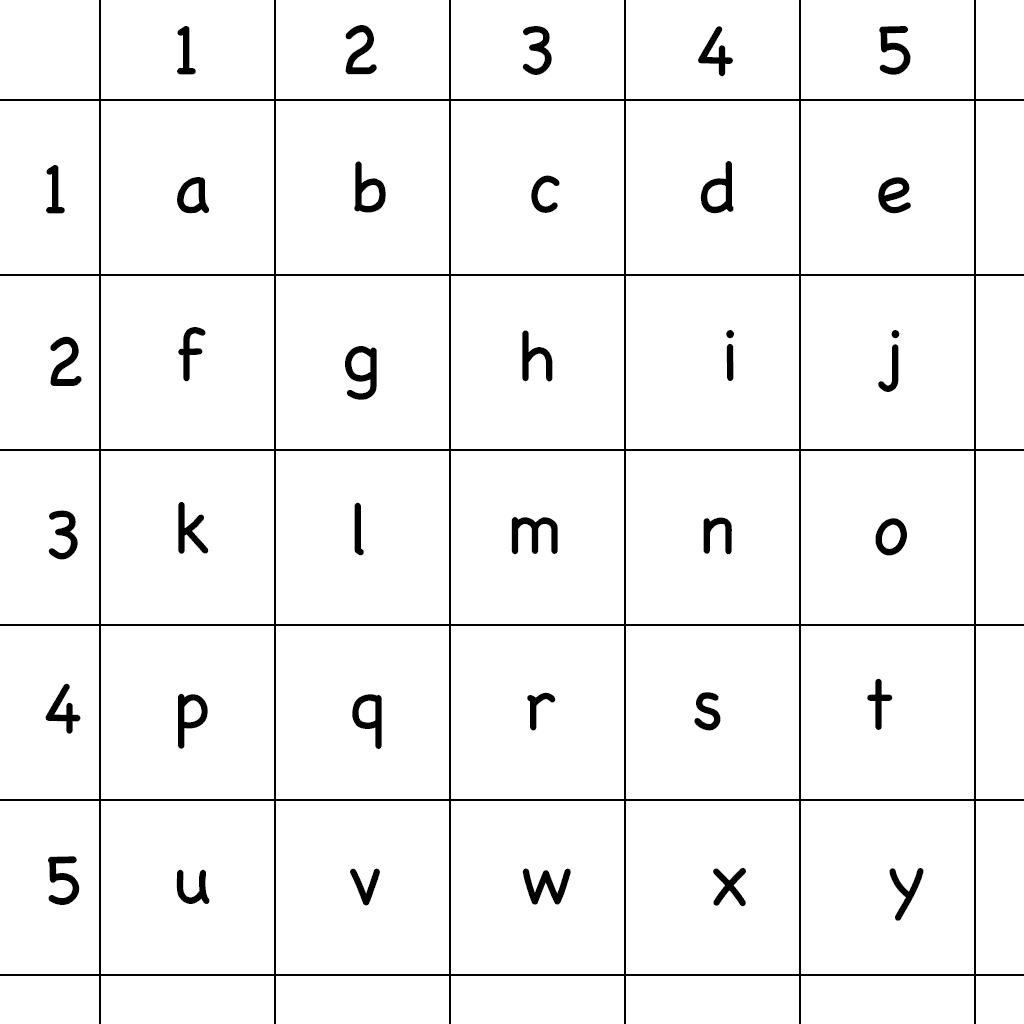

Nurse Lydia described a five-by-five grid with letters in it and scribbled an example on a scrap of paper:

She didn’t know what to do if the patient needed the letter ‘z’, but they could pluck that zither when they came to it. Did the patient understand how to use the grid? Blink twice for yes. The eyelids fluttered, but was it enough to qualify as a blink? Nurse Lydia found the process of communication frustrating. Her job was easier when she had only comatose patients to deal with—manage vital signs, administer meds, check IV and catheter, a body hooked to a machine, one kind of machine meshed with another. But a conscious patient required a bedside manner and that added another dimension to the job of nursing. This was the sort of reflection she could use when she was on the speaking circuit promoting her book and her movie.

The patient blinked twice, then four times—i.

— I. You just blinked “i”, right?

The patient blinked five times, then three—w.

— W. IW, right?

Nurse Lydia was so excited she almost missed the next letter—one blink, then another—one, one—”a”.

Methodically, the patient spun out his letters while Nurse Lydia scratched them on the back of his hospital chart: I WANT TO KILL THAT BOY.

— That boy? What boy? The boy who threw the rock at your head? Is that who you mean?

Blink, blink.

— Now, now, Mr. Moynahan, you don’t mean that, do you?

2-1, 5-1, 1-3, 3-1, 5-5, 1-1

Nurse Lydia had encountered this kind of thing before. Paralysis was like death, a loss that entailed grief. She had read Elizabeth Kübler-Ross and knew that people experience grief in stages—denial, anger, bargaining, other shit she couldn’t remember, and finally acceptance.[1] The patient appeared to have dealt with the denial stage in short order and moved straight on to the anger stage. A good nurse helped her grieving patients move through all the stages in a nice orderly way and facilitated an acceptance they could carry home with them when they were discharged from the hospital. If not with a healing of the body, at least they could leave with a healing of the soul.

— Mr. Moynahan, why don’t we make forgiveness our goal?

2-1, 5-1, 1-3, 3-1, 5-1

— Really, Mr. Moynahan, you don’t need to be so hostile. I’m not the one who bashed you in the head with a rock.

Nurse Lydia considered herself the sort of health care provider who created a healing environment for her patients which she accomplished by maintaining a positive bedside manner. Part of what it meant to maintain a positive bedside manner was that she knew when to change the subject which, in this instance, meant a shift from the boy to more pleasant thoughts.

— Mr. Moynahan, your wife tells me you’re a mathematical genius. I enjoy math. I’m a hobbyist, but competent. Proficient actually. I love a good problem. Your wife says you left a note when you went out, you know, just before you got hit in the head, something about finding an elementary solution to Fermat’s Last Theorem. Do you remember?

The patient lay with his eyes shut, regular in and out of the ventilator, green lights blipping on the monitor.

— Would you like to talk about Fermat’s Last Theorem? Maybe together we can jog your memory.

3-5, 3-1

The conversation was laborious and proceeded late into the night until the patient’s eyes closed and he fell asleep, leaving Nurse Lydia with a single page of coded notes scratched in her own cramped hand. When her shift was done and she had boarded a bus home, Nurse Lydia studied the page of notes, and she continued to study them at her kitchen table as she ate a bowl of Fruity O’s, and (in a way) she continued to study them even when she went to bed, for the notes appeared to her in her dreams as if they were being dispensed from a roll of toilet paper. The notes were not the solution; they merely pointed to the solution. They required elaboration, something which she hoped would follow in her next and succeeding shifts as she sat beside the patient’s bed and coaxed him towards the completion of his proof.

Nurse Lydia woke at noon, as she always did when she worked the graveyard shift, and she ate a bowl of Fruity O’s while reading another chapter from a book on cryptography. She went to the grocery store and bought more breakfast cereal and a box of neutrino bars which, according to the blurb, were high in fibre and guaranteed to go right through her. Before work, she took a shower, something brief and efficient, not requiring her to spend more than the absolute minimum with her body, an oddly shaped mass of flesh and bone which she regarded as God’s personal prank on her. On the bus to work, Nurse Lydia again studied the single page of coded notes, preparing herself for a fresh encounter with the brilliant but paralysed mathematician, preparing questions she hoped to ask, and anticipating answers she might get from the blinking eyes. She imagined each scene of her encounter blocked out for a documentary on the History Channel. Compassionate and mathematically inclined nurse rides bus, reads notes, looks thoughtfully at reflection in window. Compassionate and mathematically inclined nurse gets off bus. Early evening. Pan right to hospital entrance. Cue violins. The glories of modern medicine and the healing powers of sensitive health care providers.

When she stepped into the nursing station to stow her jacket and purse, she glanced at the white board and saw that the name, Moynahan, had been erased. She asked why he had been moved.

— Oh no, dear, said one of the more seasoned nurses, he died this morning.

The other nurses chatted for a minute about how sad it was that the man had never come out of his coma to see his wife one last time before he passed on. And it seemed like he might get better, too. Lydia recalled that she had forgotten to note the patient’s awakening on his chart. She had been so focused on establishing communication with him that she neglected her duties. Now, embarrassment kept her from correcting her oversight. At the same time, she was angry at herself for failing to press the patient for more of his solution to Fermat’s Last Theorem. Imagine! To sit so close to a solution and then to have it snatched away by something as arbitrary as death.

The obituary appeared the following day and Nurse Lydia noted that she could make the first visitation at the funeral home with time enough to get to work if she brought her hospital greens with her and changed in the washroom. The visitation was an awkward affair, mostly because half the people in attendance were mathematicians or professors of computer science and weren’t accustomed to speak in the common sense language of emotions but preferred instead to float around in the eternal world of mathematical truths. The widow Moynahan recognized Nurse Lydia as one of her late husband’s caregivers, but on the night shift, so she was only vaguely acquainted with the girl. They exchanged pleasantries—I’m so sorry; thank you, thank you—and then Nurse Lydia started in on a speech she had rehearsed as she rode the bus to the funeral home. She got lost part way through her speech and the widow, growing impatient and seeing that certain professors wanted to speak to her, told her to spit it out.

— He woke up, she said. On my watch. I was looking right at him and he opened his eyes.

— Why didn’t anyone tell me?

— He couldn’t move. I wasn’t even sure it was real.

— Why didn’t you get a doctor?

— I—she hadn’t thought of that—It was late. I was alone. He blinked.

— He blinked?

— Like this. Nurse Lydia blinked as if to demonstrate, then realized this was silly; everyone knows what blinking is. He couldn’t move, she said, but he could blink.

— And you did nothing?

— No. I sat beside him. The whole night. Nurse Lydia explained how she had coaxed the deceased to communicate by blinking in code, and while the process was painstaking, she nevertheless took notes and wanted to unburden herself by relaying some messages. She stared into the widow’s unblinking eyes and: He said he loved you.

The widow’s lower lip trembled.

— Oh bless you, she said, and she took each of Nurse Lydia’s hands into her own and pulled her close and kissed her on each cheek.

— He said something else, too.

— What?

— It might be difficult for you to hear.

— Better for me to hear than go wondering in silence.

— Okay then. He said—and these are his exact words—he said: I want to forgive that boy.

The tears flowed freely down the widow’s cheeks.

— Thank you.

— He seemed at peace. You know. Reconciled.

— Did he say anything else?

— Mathematical things. I have to go to work now, but maybe we could get together and talk some more?

— I’d like that. The widow pulled a business card from her purse and handed it to Nurse Lydia. Call me after the funeral and we’ll have coffee.

In the week following the funeral, the two women met for dessert and coffee, sitting at the very table where the deceased had written a final note to his wife declaring the discovery of an elementary solution to Fermat’s Last Theorem. Nurse Lydia felt so helpful it made her stomach churn. She poked at her dessert and left a crumbled heap on the plate. The widow asked again what her late husband had said that final night as he lay paralysed and blinking on the hospital bed. Nurse Lydia repeated the words she had recited at the funeral home: I want to forgive that boy. The widow smiled, saying that was sooo like her husband, and in that smile, Nurse Lydia saw a much younger woman than she had seen before, a woman too young to be left all alone for the rest of her life. Nurse Lydia went on to describe the sense she had of what passed between her and Mr. Moynahan on what would later prove to be his final night—nothing concrete she could pull from the few words he left with her, more a feeling that permeated the air around his bed, the spirit of their exchange, if you will. The widow listened and did her best to keep the tears from blurring her eyes. Lydia had the sense that when he died, Mr. Moynahan was working toward an acceptance of his condition. He may not have reached a true acceptance since, after all, a true acceptance takes time and, let’s face it, time is something Mr. Moynahan didn’t have, but she was certain that acceptance was his goal.

The widow sniffled and said:

— He was such a good person.

Nurse Lydia poked some more at her dessert. Her sliver of cake fell over like a toppled wall.

— Now if it was me on that bed … The widow shook her head. I could never be half so good. If it was me, I’d be so angry I’d want to kill that boy.

— Oh, I don’t know, said Nurse Lydia. You might surprise yourself.

The widow mused that maybe it had less to do with acceptance than with logic. The mathematical brain can detach itself from the emotions of the moment.

— I remember you saying how my husband dictated some math to you.

— A few snippets. No grand solution. You have to understand, the whole process was—It wore him out. He fell asleep.

— So his elementary solution?

Nurse Lydia shook her head.

— I’m sorry.

The two sat face to face, awkward in their silence. Nurse Lydia tried to speak, but faltered, and would have gone on that way had she not screwed up the courage to blurt it out:

— I want to use those notes.

The notes, they didn’t say much, she explained. They were more like a signpost pointing the way. She was pretty good at math—maybe not a mathematical genius like Mr. Moynahan—but pretty good. For her, mathematics was like a sanctuary. After her shift at the hospital and its stress, and (sometimes) the raw emotion of it, she retreated into the dispassionate structures of mathematics. But it was a comfort, too, like a religion. It assured her that there is such a thing as eternal truth, a place where you can plant your feet and say this is this and it will not move. So much of what she did, you know, in her day-to-day living, so much of it was so—so pointless. To meet such a man! To talk to him, even if with coded blinks. Through him, she had almost touched eternal truth. It was the closest she had ever come—please don’t laugh, she pleaded—it was the closest she had ever come to a spiritual experience. And, well, she was wondering if—

— Wondering?

— Wondering if I could have a go at it.

— A go?

— You know. Have a go at the solution.

— I don’t think it’s for me to say yes or no.

— But to use the notes.

— I thought you said they were just snippets.

— Yes. But they point the way. I want to follow where they point. And if I find a solution, I’ll publish it, but I’ll explain the circumstances, you know, about your husband and his notes and how they gave me a boost.

The widow of the late Mr. Moynahan thought “What a sad girl” but didn’t say this aloud, offering instead an opaque smile. It seemed unlikely that this nerdy nursing girl, with her fantasies of mathematical greatness, would ever make a dint in the problem that had haunted greater minds for three and half centuries, and she seemed harmless enough, so she nodded:

— Knock yourself out, kiddo.

Myrna Moynahan heard nothing for three years when a curiosity took hold and, on an impulse, she strolled into Nurse Lydia’s neighbourhood. She pressed the buzzer and a husky groggy voice answered. On hearing the name of the caller, the owner of the voice opened the door and invited the widow upstairs. When the apartment door swung in, Myrna was shocked twice over. Once, because the girl who greeted her was not as she remembered, but thin to the verge of emaciation, with hip bones visible through ragged sweat pants, and cheek bones protruding from a hollow face. Twice, because the apartment was littered with paper; not a sliver of floor showed from beneath the papers.

Nurse Lydia had become obsessed with finding an elementary solution to Fermat’s Last Theorem. At first, she had worked on it during off hours, day after day, week after week, relying on microwave dinners and floppy cardboard pizzas she ordered from across the road. Cooking proper meals took too much time, as did cleaning, and taking showers, and brushing teeth. During breaks at work, she pored over notes she had brought from home. At first, she was gruff with colleagues who distracted her, but as the months progressed, she ignored them altogether. After a year, the hospital fired her, citing a deteriorating job performance, trivial mistakes, distraction, administering the wrong meds, or the right meds in the wrong dosages, rudeness to patients and colleagues, insubordination. Since then, she’d been living off welfare, and when that ran out, savings she had stashed under her mattress, and when that ran out, handouts from her mother.

— But I’m close, she said. I’m so close.

Myrna gave her all the cash in her wallet and told her to get a decent meal. She didn’t know how anyone could think straight, much less do math, without a decent meal in her belly. She shook her head and walked home. Every month, she mailed the girl a cheque, not much, but enough for a few decent meals. She didn’t visit the girl; that would have been too upsetting.

Three years after the visit to Nurse Lydia, who had become just plain Lydia, Myrna received a telephone call. The voice on the other end was a whisper:

— I did it.

No excitement. No declaration of triumph. A simple ghostly breath.

In recent months, Lydia had grown desperate for a solution and so she had resorted to unconventional methods. She had ordered an Ouija board from craigslist, but nothing happened; she couldn’t get the pointer thingy to move, much less spell out messages from the great beyond. A séance failed to connect her with the spirit of the deceased Mr. Moynahan, and when she said the spirit of any deceased Fields Medal winner would do, the medium frowned and asked for another fifty dollars. Lydia didn’t have another fifty dollars and the séance came to an abrupt end. Despair and frustration wound around each other like a double helix strand of DNA and Lydia wondered if these two belonged to her deepest genetic makeup. Lydia resolved to jump off her balcony. What was the point of going on when she had failed at everything she had ever set out to accomplish? Out of consideration for those who would find her body, she stepped into the shower and worked the soap to a lather and there, as she passed her hands over her genitalia, something about their contour suggested a solution. Without rinsing herself off, she stumbled from the shower stall and muttered “Eureka. Eureka.” which translates roughly as “I found it. I found it.” She pulled on her least worn-out clothes and phoned Myrna to meet her at the coffee shop across from her building. As they drank coffee together, Lydia would scribble the proof before her very eyes, on napkins if she liked, just to give things a more storybook finish—destitute woman scrawls world’s most famous mathematical proof on coffee shop napkin—like a scene from a movie.

Myrna was sceptical and worried that her agreement to meet Lydia would only fuel the borderline delusions of an unhealthy mind. She found Lydia already at the coffee shop and fighting off an employee who insisted she buy something or leave. Myrna solved the issue by ordering two mocha latte cappuccinos with biscotti. Like a ravenous dog, Lydia devoured her treat and left no crumbs behind. Myrna was more genteel, dipping her biscotti in the cappuccino and savouring it as she watched Lydia scratch formulas on a growing stack of napkins. When they were done, they stepped onto the sidewalk in front of the coffee shop to say their good-byes.

— I’m happy you called me, said Myrna.

In fact, she was indifferent; the formulas meant nothing to her and she doubted the proof was real. She would need a proof of the proof which, for her, was its publication in a peer reviewed journal. If Lydia got those chicken scratches published in Annals of Mathematics, for example, then Myrna would be the first to send her a bottle of champagne. She would go further and suggest that Lydia take sole credit for the proof since it was clear that her husband’s contribution was something unquantifiable, like motivation or the planting of a seed, nothing that warranted his name as co-author.

Lydia gripped the wad of napkins and said:

— Do you see? Do you see?

She stepped from the curb and as she turned to wave good-bye, met the grille of a BMW X6. Myrna heard a whunk the likes of which she had never heard in all her life, and the squeal of rubber on asphalt, and the gasps of onlookers who stared but refused to get involved. When she was sure it was safe, Myrna rushed into the street, found Lydia flat on her back, eyes wide and turning to clouds, hands open and empty. A gust had scattered the napkins. Myrna saw some already through the intersection and pressed against shop windows. A different person might have chased after them, but Myrna chose instead to kneel beside the corpse and take one of the empty hands into her own. It was more than six years since her husband had died, and although his death had been hard, she had learned acceptance. Alongside his death, she had learned to accept that his brilliance was gone, too. Although this girl had said she would find her husband’s elementary solution to Fermat’s Last Theorem, Myrna had no expectation that this would ever happen. Now, she felt nothing—no anger or grief—to see the scribbles disappear on the wind. As she viewed it, just as boiling water’s proper state is to be steam, so the elementary solution’s proper state is to be elusive. She had worked hard for this feeling of acceptance and she was damned if she would let some failed nurse spoil that for her.