Rob Ford’s graffiti Nazis are fanning out like pesky little rodents through all the streets of Toronto. I just saw my first “Stop Graffiti Vandalism Now” sign. We have our very own war on terror, but scaled down for the suburbs. If municipal projects have patron saints, the anti-graffiti campaign must have St. Jude, the patron saint of pointless causes.

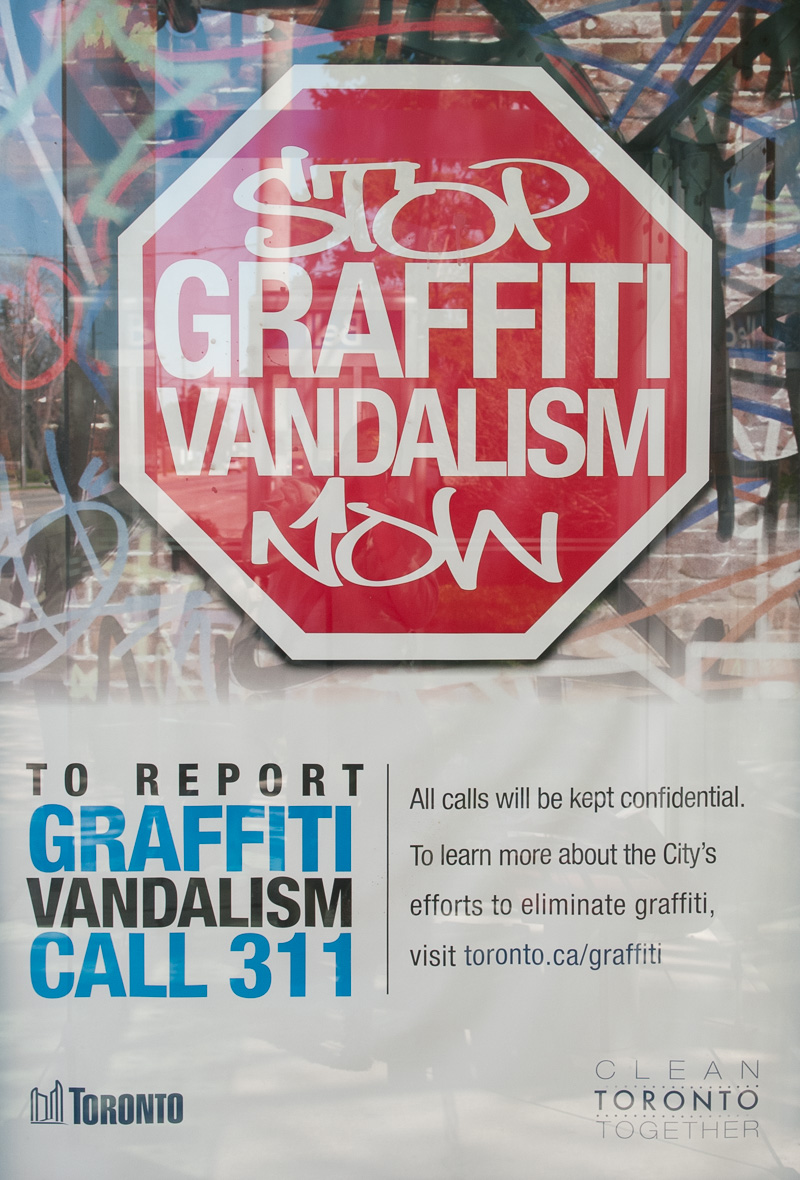

The Anti-Graffiti Poster

First, let’s take a look at the poster, on display in bus shelters throughout the city. Predictably, it features a big stop sign, but what’s curious about the stop sign is that the words “stop” and “now” are written as if spray painted. They mimic graffiti tags with two ironic results:

1. The (stop) sign appears to confer legitimacy upon graffiti as a form of communication. In this instance, the communication is both visual and verbal. Like any typography, the letters on the sign spell out words, but their forms convey meanings too. Here, those meanings appear to be at variance with the intended message. See how those beastly words of subversion and disorder—”GRAFFITI” and “VANDALISM”—appear in an authoritarian Gothic font, while the imperative words of authority—”STOP” and “NOW”—appear in a more whimsical hand. The confusion of words and fonts plays up the free exchange that takes place between authorities and graffiti artists, the borrowing of conventions, the interpenetration of discursive modes which refuse to be isolated in neat containers. Concrete flows out of its square molds while spray paint wraps around corners. Things refuse to stay put, continually reminding us that they belong to a single larger world whose logic is the privilege of no one.

2. By its very garishness, the poster undermines one of its stated aims: to make Toronto “cleaner and more vibrant” and “a more attractive place for everyone.” I find it hard to believe that these posters in their prominent public locations are being touted as a way to beautify the city.

Goals of the Anti-Graffiti Campaign

Second, let’s take a look at the campaign’s stated aims. Although the municipal website does make reference to hate graffiti and gang-related tagging, it’s important to note that these are already addressed by the police under the authority of the criminal code and other statutory provisions. The same can be said to the extent that graffiti represents property damage. The police don’t need more teeth. In fact, there are no by-laws the city could enact that would give the police more teeth because it doesn’t have the jurisdiction to do so.

The new municipal by-law, Rob Ford’s great swipe at graffiti, concerns itself entirely with aesthetics. It boils down to this: if a by-law enforcement officer serves notice on the occupant or owner of a building whose exterior has graffiti on it, the occupant/owner has to clean up the building within the stipulated time or face a fine of up to $5000, subject to an exception for “Art Murals.”

If you didn’t know the difference between graffiti and an Art Mural,” the by-law answers the question with definitions:

ART MURAL — A mural for a designated surface and location that has been deliberately implemented for the purpose of beautifying the specific location.

GRAFFITI — One or more letters, symbols, figures, etchings, scratches, inscriptions, stains or other markings that disfigure or deface a structure or thing, howsoever made or otherwise affixed on the structure or thing, but, for greater certainty, does not include an art mural.

The difference rests in the word “designated” which might better be translated as “because we say so.” Art beautifies. Graffiti disfigures or defaces. Let’s compare two examples. Here is a work of beauty.

And here is a work of disfigurement.

Which stirs you more? Can you even tell? Might your opinion differ depending upon your mood? According to the city website, art murals are “an important deterrent to graffiti and can dramatically improve the look of our neighbourhoods.” It almost makes art murals sound like pre-emptive graffiti.

I don’t think the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto is about to resolve age-old aesthetic conundrums any time soon. Instead, as we glean from the word “designated,” the city affirms a different age-old truism: there is a relationship between aesthetics and power. Those in charge try to determine what counts as beautiful. Those without power push back (or sideways) with an anti (or alternative) aesthetic.

Rationale of the Anti-Graffiti Campaign

Third, let’s look at the campaign’s rationale, summarized in four bullet points from the city’s web site:

- Poses a risk to the health, safety and welfare of a community.

- Promotes a perception in the community that laws protecting public and private property can be disregarded with impunity.

- Fosters a sense of disrespect for private property that may result in increasing crime, community degradation and urban blight.

- Creates a nuisance that can adversely affect property values, business opportunities and the enjoyment of community life.

The city cites no evidence to support its claims. I’d wager that it sought none. The claims are axiomatic. They are thrown out as things which Leonard Cohen assures us “Everybody Knows” (that was an ironic statement, in case you missed it).

All four points use the word “community,” a cozy word given that this by-law is the municipal equivalent of a “tough-on-crime” bill. And yet the word deserves close scrutiny, especially, when the graffiti in question appears in places invisible to most of Toronto. “Community” has such a nice middle-class ring to it. Surprising, then, to learn that much of the city’s graffiti decorates the walls of people’s homes. Look under any bridge in the city and you will see two things: graffiti, and evidence of permanent dwelling places. It’s ironic, too, that three of the points seek to secure property while the fourth speaks to the related concern of “health, safety and welfare.” I bet the people living under our bridges feel their concerns are well-secured by this community initiative.

One of the problems with the city’s rationale(s) is that it assumes a univalent picture of graffiti. The only thing graffiti does is strike at the social order; above all else, it is an assault against our property. I’m more inclined to view graffiti as the expression of many different stories. Yes, for some, it’s simple vandalism or the product of boredom. But I doubt, for most, it’s that simple. It’s wanting to be heard. It’s wanting to be known. It’s wanting to stake some ground. It’s wanting to make something beautiful. It’s wanting to do the impossible. It’s wanting to obliterate someone else’s work. It’s wanting to decorate a home. It’s wanting to release a valve. It’s wanting to get laid. It’s wanting to scream in anger. It’s wanting to be a prophet. It’s wanting to tell a joke. And for some, like the guy living under the bridge, maybe it’s wanting to be human, giving warmth to bare concrete and steel.