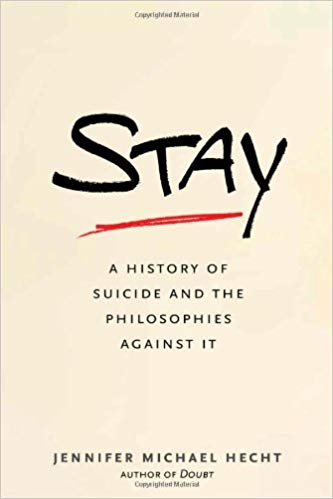

Stay: A History of Suicide and the Philosophies Against It by Jennifer Michael Hecht (Yale University Press, 2013) is an odd book. It’s odd in that there seems to be a divide between what it claims to be and what it is. Note that I didn’t say it’s a bad book. It’s a good book. But it’s not the book it thinks it is.

1)

Stay thinks it’s a book exhorting people to choose life over death. Lots of other books have done that too (and Hecht surveys many of them), but Stay distinguishes itself from other books by asking: can the call to choose life be made without relying on religious (or theological) arguments? Hecht tries to hammer out a life-affirming ethic rooted in secular concerns.

In her Preface, Hecht reveals the motivation for the book: she lost two friends to suicide. It’s a wrenching thing to lose people this way. I know this from personal experience. Alongside the grief is a nagging self-doubt. Is there something wrong with me that I didn’t notice the signs? Is there something I could have said or done? In part, Stay is Hecht’s answer to those questions.

In terms of experience, I go one further than Hecht. Once upon a time, I was deemed a risk to myself and had the pleasure of a lengthy stay in a psych ward. I repeated the pleasure three more times. I remember how, afterwards, eyebrows went up when I told the uninitiated that of course I thought about killing myself. That was pretty much all I thought about. Right down to the details of execution, wording of the note, putting my affairs in order. Why the fuck do you think they stuck me in here? (You lose your tact in a psych ward.) I get the impression that most people think of “clinical depression” as a vague romantic melancholy. Unleash me in the Lake District to moan about natural beauty for a couple weeks and I’ll be fine.

My experience gave me a good dose of skepticism about my religious inclinations, too. Until that time, I’d been an active member of a church community. During my more than four months as a psychiatric in-patient, I received only one visit from a member of that community (the minister, who gave me communion on Christmas morning). While religious communities are good at coming up with abstract arguments about why people shouldn’t kill themselves, they’re not so good at doing anything about it. An afternoon sitting with a psych patient, assuring them they’re not alone, is worth a library full of religious books. The answer to failed religious arguments isn’t more arguments (even if they are secular arguments). The answer is to dispense with arguments altogether. What we need are hugs, walks with friends in the evening, and the assurance that we belong in our community.

2)

What makes the book an odd book is that, although you’d expect an ethic grounded in secular concerns to rely on historical analysis and social science data (which it sometimes does), nevertheless, a good portion of the material in Stay draws on literary sources. I suppose you could say that this is more anthropological than literary (using the literary texts as evidence of social attitudes in the periods in which they were written) and, sure, Durkheim gets a mention here, but I’m more inclined to treat literary texts as, well, literary texts. As a survey of attitudes, it’s difficult to argue that literary texts represent a sample population of more than one. As a strategy of literary criticism, by all means, use social science as a point of entry into the text, but treat it as one among many interpretive approaches. However, Stay doesn’t purport to be literary criticism and so, often, the social science approach is the only approach to the texts Hecht uses.

For example, Hamlet makes an appearance, as it seems to in just about any book on suicide. The prince’s famous soliloquy presents the kind of rumination that is typical of a person suffering from clinical depression. “To be or not to be …” etc. Hecht gives a close reading which ends with: “What is certainly clear here is that attitudes [in Jacobean England] were changing, and the church’s argument that God alone is allowed to take a life is given no role in the deliberation.” That sentence is true only as far as that speech goes. If we expand our view to take in the whole play, then she’s wrong. In another scene, Hamlet watches his uncle at prayer and debates whether or not to kill him. He decides to let his uncle live, not out of mercy, but because he doesn’t want to kill him in a shriven state since that would guarantee that he goes to heaven. Hamlet wants to send him to hell. (The irony is that, after Hamlet leaves, Claudius confesses that his heart wasn’t in it when he was praying; it turns out Hamlet could have sent him to hell after all.) My point is that, contrary to Hecht’s claim about the church’s argument etc., Hamlet, is chock full of medieval religious superstition. But so what? A Midsummer Nights Dream is chock full of nymphs and fauns but we don’t take Bottom The Weaver’s dream speech as evidence of changing Jacobean attitudes towards Greek mythology.

Personally, I find it hard to take anything in Hamlet as evidence of attitudes in Jacobean England. I mean, come on. The play’s action is driven by the demands of a ghost. Did Jacobeans believe in ghosts? I don’t know. Does it matter? Probably not. The ghost serves as a conceit that drives the plot, the same way zombies drive the plots of 21st century novels. The fact that I don’t live in fear of zombies knocking down my front door doesn’t mean I can’t enjoy them in the novels I read.

As for suicide, Hamlet is a late Renaissance tragedy. It conforms to a literary convention, not the DSM-V. Hamlet has to die. We know that from the first scene. To qualify as a tragedy, Hamlet has to know he’s going to die too. What makes Hamlet an early modern play instead of, say, a Greek tragedy, is that it couples death with the question of free will. Hamlet can spend the whole play waffling if he wants to, but in the long run that won’t keep death away. He can passively succumb, or he can choose to meet his death. What ennobles him is agency. He elects the inevitable. In conforming to the demands of a literary convention, Shakespeare is not laying out an early modern psychology of suicide. The two concerns might overlap, but they’re still different concerns.

As a late modern, Albert Camus offers a gloss on the tragic impulse. Hecht cites his opening essay in The Myth of Sisyphus in which he famously states: “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide.” He grounds the problem on the fact of absurdity as a condition of life. As with the tragic convention of Jacobean drama, so the absurd convention demands a choice. We can waffle, or we can embrace the absurdity of our lives. (Please don’t force me to point out that this doesn’t have to be taken as a literal discussion of suicide.)

3)

My personal inclination is to read Stay as a literary survey of suicide. On those terms, it’s worth the read even if it does treat literature as source material for an anthropological investigation. However, as an exhortation to stay, it makes a serious omission. It doesn’t offer an argument why life is worth living in the first place. I don’t want to sound flippant, but if, as the title suggests, this is a philosophical investigation, then first principles are important. Otherwise, all her reasons collapse. For example, when she speaks of suicide as a violent act that inflicts pain on those left behind, it’s possible to answer that those left behind wouldn’t suffer if they had the good sense to kill themselves. Her argument only works if those left behind go on living because there is something intrinsically good about life.

Yes, I believe there is something intrinsically good about life, but I’m not so sure about human life. I wonder if there isn’t a measure of arrogance in my claim that I have the right or, as Hecht might suggest, the duty to go on living. When I expand that right or duty to all seven billion of my brothers and sisters, and then consider what that means for life on our planet, I wonder if suicide might not be an affirmation of life. Only a different kind of life. Ants. Deer. Dolphins.

4)

Another omission is the failure to acknowledge a cultural dimension to suicide. The values at stake are not absolute but are culturally contingent. Traditional Japanese culture, for example, provides a foil that helps to reveal the Eurocentric values at play in Hecht’s discussion. While modern Japan adopts a more Western affirmation of life, the memory persists of suicide as the ultimate expression of a code of honour. It enacted values that were and remain opaque to Western sensibilities. While a discussion of non-Western suicide would produce an enormous book and take Hecht beyond the scope of her concerns, it might be helpful at least to acknowledge its place in the wider range of possible cultural values.

5)

Finally, it may also be possible to argue that values concerning life differ along gender lines. She writes as a woman in response to the suicide of women. I write as a man in response to the suicide of men. My situation is compounded by the fact that as a middle-aged middle-class male who has had recurrent major depressive episodes, I fall into a high risk category. I take seriously the agency argument. I wonder if this is more a male thing. The possibility of suicide is a moral comfort. If I lose control of my situation, I always have a way to take back control. The reasoning behind this attitude represents an utter contradiction of Hecht’s thesis: there is no such thing as choosing life; the most you can choose is the deferral of death.