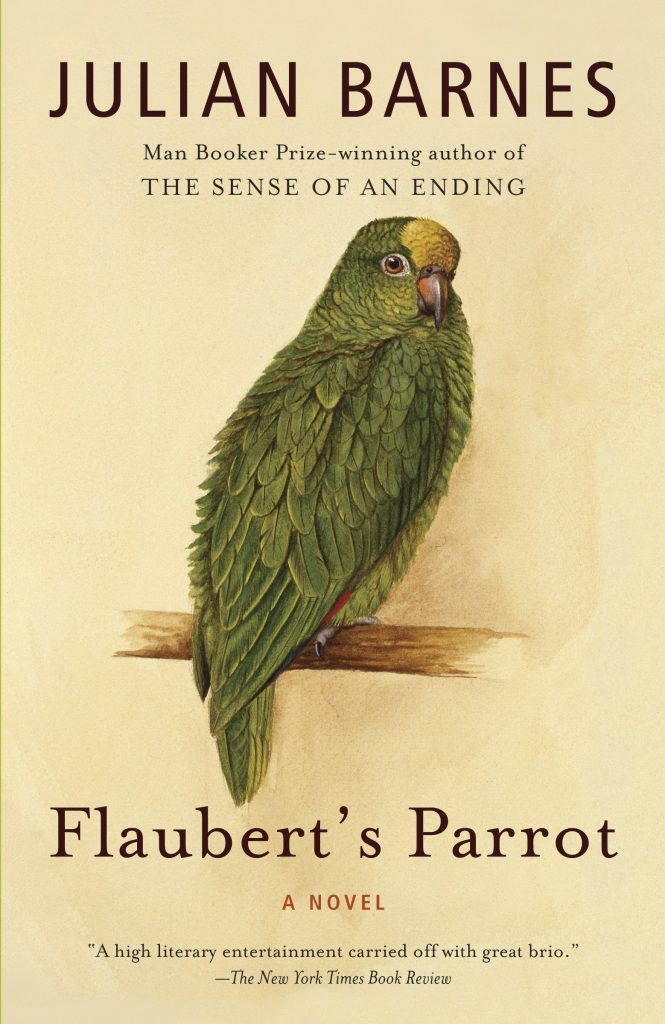

Flaubert’s Parrot is a literary romp by Julian Barnes that tracks the obsessive research of a widowed doctor named Geoffrey Braithwaite. Along the way, Dr. Braithwaite considers all kinds of arcane details about the famed French novelist: his sexual proclivities, plots for unwritten novels, and the use of animals in his writing. This last includes the stuffed parrot which he had borrowed from the Museum of Rouen and which sat watch over his desk as he wrote Un coeur simple, the tale of a woman named Félicité who came to believe that her stuffed parrot, Loulou, was the Holy Ghost.

Flaubert’s Parrot is also the occasion for some sly literary theory and leads us into a consideration of the relationship between the reader and the author. Braithwaite is trying to “get at” Flaubert, but is there really anything to get? All that remains of Flaubert are his novels, his letters, a couple crumbling statues in public squares, and two stuffed parrots competing for the claim of inspiration for Loulou.

But as the novel progresses, we realize we’re looking in the wrong direction. Barnes is playing games with us. He offers this image:

Reading [Mauriac’s] ”memoirs” is like meeting a man on a train who says, ”Don’t look at me, that’s misleading. If you want to know what I’m like, wait until we’re in a tunnel, and then study my reflection in the window.” You wait, and look, and catch a face against a shifting background of sooty walls, cables and sudden brickwork. The transparent shape flickers and jumps, always a few feet away. You become accustomed to its existence, you move with its movements; and though you know its presence is conditional, you feel it to be permanent. Then there is a wail from ahead, a roar and a burst of light; the face is gone for ever.

As we observe Brathwaite pursue his obsession, we realize that the arcane details about Flaubert are neither here nor there; they are like the passing background. We turn our intention instead to Braithwaite himself and discover the subtle revelation of details that, in the context of this novel, pass for plot. We learn that his wife, whom he loved, who perhaps loved him but nevertheless had numerous affairs, committed suicide. The reason for her suicide is as elusive as the truth of Flaubert’s parrot. And Brathwaite is just as elusive to us. As we finish the novel, it is like rushing out of a tunnel into the full light of day: Braithwaite’s face is gone for ever.

The twist, of course, is that Braithwaite is a fictional character. The obvious question arises: can we apply this train-in-a-tunnel image to “get at” Julian Barnes. Is his presentation of Geoffrey Braithwaite a kind of backhanded way to reveal something of himself? Does Barnes intend to reveal things about himself? Or is that merely the inevitable consequence of writing? Is the decision to write fiction a kind of disinformation tactic to obscure the truth about Julian Barnes while still allowing him to get things off his chest?

Since one good turn of the screw deserves another, does my writing about Barnes end up revealing unrelated truths about me? If I go on long enough, will you end up discovering the secret of my sexuality, my cannibal fantasies, my love of model railroading? Is my blog — is all writing for that matter — nothing but surreptitious autobiography? Should I adopt a more Freudian stance and assume that all expression finds its source in unconscious desire?

Or maybe we can flip the whole argument on its head and suggest that all factual writing, from news reportage to autobiography, is fiction. Why not? After all, we call news items “stories” and writers like James Frey have made it clear autobiography need no relation to the facts in order to succeed as good writing. In my blogging, it’s possible I’ve never read any of the books I discuss. I never read Flaubert’s Parrot. Everything I’ve said, I constructed from things I’ve pilfered from other people’s web sites. In fact, I am a bot. I harvested my ideas with an algorithm.

Squawk.