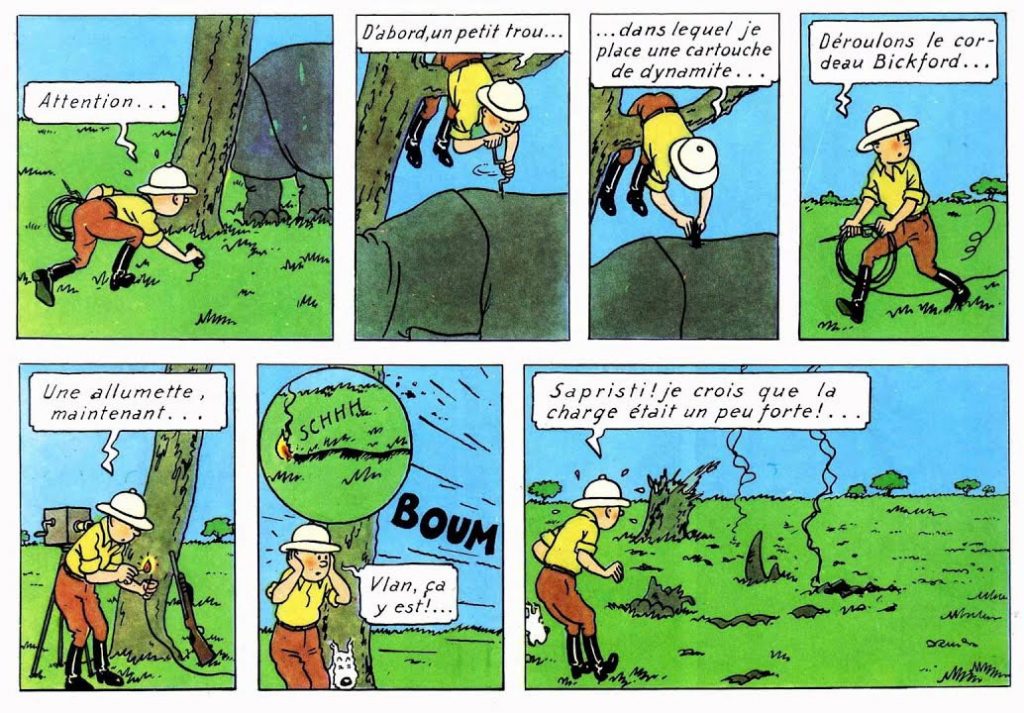

The Guardian reports that a Congolese man, Bienvenu Mbutu Mondondo, now living in Belgium, has applied to the Belgium courts to have Hergé’s Tintin in the Congo banned. He alleges that it is racist. Hergé created the cartoon in 1930 when the Congo was a Belgian colony. He portrays native Africans as ignorant, superstitious people who defer to the Great White Man. The original black and white version includes a scene in which Tintin blows up a rhinoceros with a stick of dynamite. Hergé deleted this scene when he produced the colour version, but you can still view it at p. 101 on the scrbd web site. [subsequently deleted]

I don’t think there’s any question about the cartoon’s racist content. The question is what to do about it. As the Guardian points out, three years ago when a complaint in the UK resulted in restricted access to the book, it vaulted to 5th place on Amazon’s bestseller list.

My knee-jerk white liberal pseudo-intellectual response is to defer to freedom of expression and make an appeal to the powers of critical thought. Certainly that’s been my approach in my own household: my children have always enjoyed complete access to television and the internet, but my wife and I have tried to moderate this freedom by creating an ethos where everything is questioned.

However, I’m growing disillusioned with the nice white deference to freedom of expression. Tim Wise provides a revealing thought experiment that shows up the inadequacy of my nice white liberalism. [blog removed] He invites people to imagine what it would be like if the Tea Party was black.

Imagine that hundreds of black protesters were to descend upon Washington DC and Northern Virginia, just a few miles from the Capitol and White House, armed with AK-47s, assorted handguns, and ammunition. And imagine that some of these protesters—the black protesters—spoke of the need for political revolution, and possibly even armed conflict in the event that laws they didn’t like were enforced by the government? Would these protester—these black protesters with guns—be seen as brave defenders of the Second Amendment, or would they be viewed by most whites as a danger to the republic?

The Tea Party people—white people—have been allowed to engage in public protest—spitting on members of Congress, using racial epithets, talking in general terms about violent opposition—in the name of tolerance and freedom of expression. As Wise suggests, if it were black people engaging in this behaviour, it is likely that they would be met by law enforcement officers in riot gear.

Two observations:

1. In a tolerant society, no freedoms are absolute.

2. Freedom of expression must always be balanced against countervailing freedoms, like freedom from fear.

If we apply Tim Wise’s thought experiment to Tintin in the Congo, how would it play out? Imagine a world in which the native residents of the Congo had established an empire which, several centuries ago, had conquered Western Europe and all its white people. Now, in the 21st century, the West has achieved independence from the Congo’s oppressive rule. We claim to live in an enlightened time. Nevertheless, remnants of that colonial period can still be found in our shops and online. These include depictions of white people as primitive and ignorant, as people who are always obsequious before black superiority. Although we whites object to the depictions, we’re told not to worry about it. There’s a higher value at stake: freedom of expression. We all are equal in our enjoyment of this freedom. But that freedom also entails a certain responsibility. Sometimes we have to suck it up and suppress our petty grievances for a higher principle.

Applying this thought experiment makes the appeal to freedom of expression seem disingenuous. It comes off sounding like one more rationalization of a racism that lingers in our postcolonial conversations.