Brothers and Sisters, the Lord has called me to embark upon a quest. It is a quest to uncover the workings of the evangelical fundamentalist Christian mind. I expect it will be a short journey. Brevity notwithstanding, I expect my quest to be fraught with perils. So I ask you to pray for me. Or at least get your hair nicely done and stand over me with your eyes tightly shut and your arms outstretched. One of my first perils is an in–box crammed full of newsletters, links to zines, appeals for cash, action alerts, and email petitions calling for the government to post the ten commandments above every urinal in America.

Just the other day I received such an email that stood out from all the rest. It was congratulatory in tone, applauding a library in Bloomington, Illinois for removing a pornographic film without fuss nor muss after a concerned citizen named Bill Swearingen lodged a complaint. Two things struck me as odd:

1. Why no mention of the title? How are we supposed to evaluate the complaint if we have no information?

2. What’s with the library? Aren’t libraries supposed to be the last great bastion of freedom of speech? Aren’t they the institutions that fight to the death over issues of censorship? If a library rolls over that easily, then the movie must be really disgusting, right?

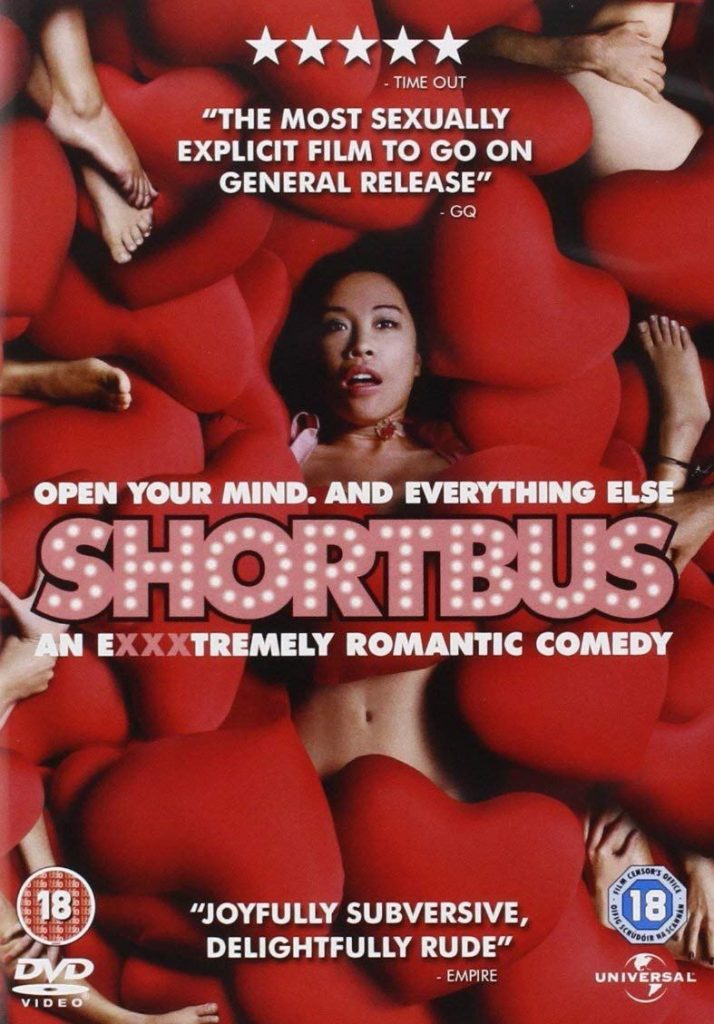

A great virtue of living in the Google Age is that certain types of investigative research are sublimely simple; within 15 seconds I learned that the banned film is Shortbus. Within another 15 seconds I had pulled a torrent from piratebay and an hour later I was watching the film. In the spirit of empiricism, I had to see for myself. And, hey, isn’t that what quests are all about?

Shortbus

So what’s Shortbus? Well, it’s a 2006 film starring Canadian actress Sook–Yin Lee as a New York based couples counselor named Sofia. The film was screened at Cannes and was a critical success abroad. Nevertheless I can understand why it might rile fundamentalists. Here are some of the more notable reasons:

1. Unsimulated sex

2. Unsimulated gay sex

3. A vibrating egg

4. Critical success in Europe

5. NYC

6. Fat people

7. A rich soundtrack

8. People enjoying themselves

9. Authentic emotions

One of the challenges of Shortbus is that there’s a good chunk of explicit (i.e. unsimulated) sex in the first three minutes. Solo, straight, gay, S & M fetishism, voyeurism. It’s all there. So if you’re predisposed to be offended, it saves you the trouble of having to watch the whole film in search of that elusive nastiness you’ve heard all about. Instead, just click “play” and there you go. The film assumes of its viewers a worldview—one which engages ambiguity (and doesn’t mind watching gay sex). But if you don’t share that worldview, or at least have empathy for it, then you’ll never make it past the first three minutes. And what about the character who reminds us that “voyeurism is participation too”? If you’re a fundy pastor watching men in a three–way, what does that make you? Probably uncomfortable. Or more likely angry. You click the remote, then vent at the hapless librarian.

Is Shortbus Porn?

A superficial glance says yes—especially given the etymology of the word “porn” which comes from the Greek word porneia which means “fornication.” And there’s a lot of fornication in Shortbus. Then again, there’s a lot of fornication everywhere—including the Bible, but I haven’t heard anybody calling for us to ban the Bible yet. Sorry, but porn as “having sex” isn’t much of a criteria.

What about porn as exploitation? Most people agree that representations of violent exercises of power by one person over another, particularly sexual violence against women, is a hallmark of pornography. But what about the rape scene in Boys Don’t Cry which garnered Hilary Swank an Oscar? Is that pornography? The typical response distinguishes porn from art by reference to intent. Aristotle worked this one out 2500 years ago when he said the purpose of art is to teach and to delight. Ironically, it’s on this very non-Christian footing that fundies ground their often graphic films about the evils of masturbation, fornication, adultery, sodomy, etc. These graphic depictions are for our moral instruction. But modern critics skewered intent as a yardstick for merit with the so-called “intentional fallacy.” This plunged us into territory that is often described using a term that is like nails on a chalkboard to fundies—relativism.

In any event, it’s difficult to characterize any of the sex in Shortbus as exploitive so let’s move on.

It’s not my intention to spend any more time down the art/porn rabbit hole. Instead, I’ll point out a few themes in Shortbus that I find compelling. As to whether or not it’s porn, watch it and decide for yourself.

Feeling and Numbness / Connection and Distance

The film follows the lives of several people whose paths converge at locale called Shortbus which is owned by Justin Bond (playing himself).

There is Sofia, the couples counselor who is married to Rob (Raphael Barker). She has never achieved an orgasm. The film is ostensibly an account of her quest for an orgasm. At the same time, her husband is plagued by feelings of inadequacy—he’s unemployed and can’t give his wife what she wants.

Sofia is counseling Jamie (PJ DeBoy) and Jamie (Paul Dawson) who has recently reverted to calling himself James. James is trying to assert a distinctive identity in a relationship that isn’t working. James, an ex–prostitute, now lifeguards and has recently pulled a body from the pool where he works. He tries to revive the man, but without success. We see that James and the body have a lot in common.

James is suffering from depression and has been preparing a farewell tape for Jamie. He wants to open up the relationship (hence the meeting with Sofia) and they end up connecting with Ceth (Jay Brennan). Privately, however, James intends to commit suicide and Ceth is his way of ensuring that Jamie won’t be left alone.

Caleb (Peter Stickles) is the voyeur who lives in the building opposite Jamie and James and has been photographing the development of their relationship for two years. His lack of connection speaks for itself.

Finally, there’s Severin (Lindsay Beamish), the dominatrix, whose longest relationship is with a trust fund brat client whom she regularly beats. Along the way she meets with Sophia in a sensory deprivation tank and (during a game of truth or dare at Shortbus) talks to James in a closet. In a penetrating moment of insight, James confesses to Severin that it all stops at the skin; he’s never let anyone fuck him, not even Jamie. This is when it becomes obvious that, all along, the film has been dealing with something more than sex.

James attempts suicide in the pool where he found the body, but Caleb has been stalking him and pulls him out. As Jamie and Ceth watch the farewell video, James lets Caleb enter him. Meanwhile Rob has paid a visit to the dominatrix. Just as he can’t give Sofia an orgasm, there’s something she can’t give him either. Maybe it’s the sense of being real.

Then the lights go out. The climax happens during the black out of August ’03. Everyone gathers in candlelight at Shortbus and Justin Bond sings the final number: “We all get it in the end.” And Sophia does too! In the quiet, in the darkness, people begin to feel again and connect with one another.

In the end, or in the final analysis, or whatever, I find all the fundy caterwauling tiresome. And I can’t believe I overlooked this film. I thank the fundies for drawing it to my attention. One of the best I’ve seen all year.