I became an associate of the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto (A.R.C.T.) when I was 17, too old to qualify as a prodigy, but pleased with myself all the same. It was an awkward time because I had almost a year to kill before I began more formal studies at the university level and I was looking for something to challenge myself in the interim. Yes, I would continue to practise the piano and to take lessons and to learn new repertoire, but I needed something more. I needed a sense that my life was moving forward.

Sergei said he understood how I felt and he had just the thing for me. Sergei was my piano teacher, the one who had guided me through my performance exams at the Conservatory and would continue to coach me until I went to university. While Sergei was a great piano teacher, I didn’t believe him when he said he understood how I felt. This was at the end of our first session together after I had completed my performance exams; it was the musical equivalent of a debriefing. At the end of the debriefing, when I intimated for the first time that I was anxious about my impending year in limbo, Sergei asked if I trusted him. When I nodded, he took up his jacket and told me to follow him.

We stepped outside and Sergei hailed a cab (Uber was not yet a thing in those days), telling the driver to run up Mount Pleasant Road to the cemetery entrance. We were going to visit Glenn Gould’s grave. By the time we reached the entrance, they had locked the gates for the night so I assumed we’d turn back and catch a cab to the nearest subway station, say good-bye and go our separate ways for the summer. But Sergei was undeterred by something as trivial as a locked gate. He pulled me away from the entrance, further along the wrought iron fence where an overhanging tree offered cover. There, he made me interlock my fingers and give him a boost. Rising into the dark foliage, he gripped a branch and passed hand for hand over the fence. When he had gone far enough to clear the fence, he dropped to the soft ground, rolling sideways to absorb the shock of the impact. From the perspective of a 17 year old, Sergei had seemed impossibly old, and so it was surprising to see how limber he was as he swung from the branch, and how agile when he dropped to the ground and rolled onto his side. With the benefit of hindsight, I realize that Sergei was not so old after all, maybe 35, with the lithe body of a man who enjoyed regular exercise and healthy food. When Sergei rose from the grass, he stretched his arms through the iron bars of the fence and in turn offered me his interlocked fingers: subject and recapitulation.

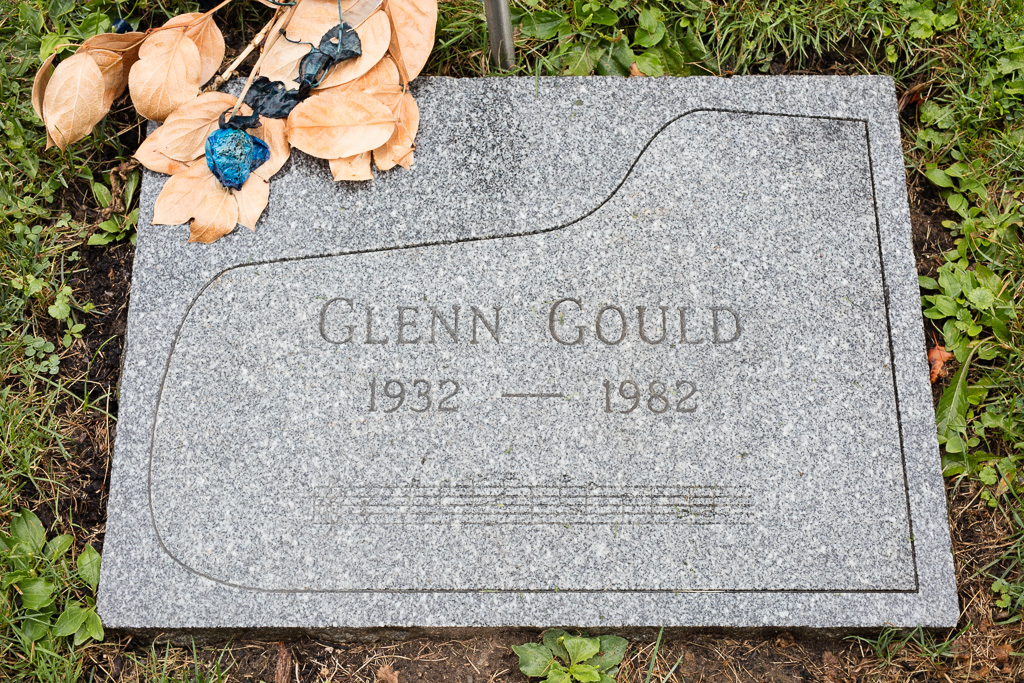

In the glowering dusk, it was difficult to find our way, but Sergei insisted he had been this way many times before. For a man of towering stature, Glenn Gould’s grave is surprisingly modest: a flat granite slab, a few simple words enclosed by the stylized lines of a piano. In absolute terms, the piano is no bigger than Schroeder’s toy piano in the Peanuts. I was expecting something more elaborate.

Sergei said we hadn’t come there to see Glenn Gould’s grave per se, but only to use it as a marker in our search for something else. Naturally, I asked what. Sergei answered me the way Bruckner wrote a symphony: he’d come to his point eventually, but I’d have to wait for him to get the preliminaries out of the way; yet without the preliminaries, the point would dissipate like a morning fog and leave me with not much of anything. This was Sergei’s way.

According to Sergei, Glenn Gould was 14 when he completed his final piano exam at the Royal Conservatory of Toronto and, like me, he felt anxious at the prospect of a year in limbo. He was too young to be taken seriously but too good to allow stagnation to creep into his life. After a few weeks moping around the family home, practising Bach preludes and fugues, walking his dog, and exasperating his parents who (let’s be honest) had no clue what to make of their son, the young prodigy hit upon an idea that would change the course of musical history. No, not an innovative interpretation of the Goldberg Variations. The Piano Fight Club. PFC.

Gould hosted the first PFC in the back yard of the family home while his parents were attending a dinner party, a few contemporaries from the Conservatory, all of whom suffered self-esteem issues, all of whom were routinely bullied as “fucking music geeks.” Although one of the guests put his hand through a window and suffered career-ending damage to a tendon, all agreed the PFC was a great success and should be developed into something bigger. Most importantly, it should be an invitation-only secret society restricted to pianists who had graduated from the Conservatory or demonstrated equivalent skill. The last thing they needed was to have uninvited tone-deaf bullies crashing their fights. The boys held their second PFC on the chancel of Timothy Eaton Memorial Church before first light on a Sunday morning. It was here that Gould presented his famous rules of the Piano Fight Club.

Sergei turned to me and asked if I could tell him the first rule of Piano Fight Club.

Don’t talk about Piano Fight Club?

That’s the second rule. The first rule of Piano Fight Club is: Don’t hurt any fingers. If you hurt your opponent’s fingers, then you can expect to be blackballed. Agencies will turn their backs on you. Performance gigs will dry up. Recording contracts will vanish. If you hurt your own fingers, well, that’s its own punishment.

Sergei knelt in the cool grass, lowering his head to the grave marker and drawing a sight line along the etched piano’s straight edge. Extending the line a hundred metres or so across the cemetery lawns, it met the great bronze doors of a mausoleum. Sergei pointed the way and together we walked between headstones and ancient maples. A full moon had risen above the treetops and draped the graves in its pallid light.

Sergei explained that Gould modelled the PFC on Frédéric Chopin’s bicycle club, known as La Société Parisienne de Vélo. People suppose that Chopin died of complications from tuberculosis. However, the little known minutes of La Société reveal that in 1849 Chopin rode his velocipede into a tree and suffered a blow to the head which modern medical experts believe produced a subdural hematoma. Bicycle historians speculate that Chopin’s accident provided the impetus for the invention of the bicycle helmet. More significantly, they now agree that La Société was the precursor to the Tour de France. Pianists are divided on the question of secrecy, some arguing that Chopin should have enforced La Société’s early rules around secrecy to prevent the rise of crass commercialism associated with the Tour de France, others arguing that openness is a good thing, pointing to a counterintuitive surge in children taking piano lessons after the 1910 relaxation of the rule prohibiting non-pianists from participating in the famous bicycle race.

When we reached the entrance to the mausoleum, Sergei rapped on the door in a specific rhythm: one short rap, a pause as if to breathe, a second short rap followed by another pause, then three more short raps in quick succession. Sergei asked me what music the rhythm referenced. I was bewildered by the utter strangeness of the evening, and I couldn’t think clearly. But when I paused to catch my breath, the answer came to me. Sergei noted the look of recognition in my eyes and grinned: the opening notes to the Aria which introduces the Goldberg Variations. Nothing could be more fitting as a secret knock to a piano fight club.

Remember those five notes, he said.

I came back with: Technically, it’s only three notes. The other two are mordents.

You’re such a fucking nerd, he said. You’ll fit in just fine.

I heard a bolt slide from its recess, then the clang of a heavy metal latch, and the great bronze door swung into a profound darkness. I heard the strike of a match on the stone wall and watched as lithe fingers touched the resulting flame to the wick of an old oil lamp. A woman held the lamp and, while I thought I recognized her, I didn’t want to presume as the lamp’s wild flickering light distorted her appearance. The woman smiled when she saw Sergei, but the smile fell away when she turned to me.

Sergei motioned to me and said, Angela, here’s the pupil I was telling you about, the one who just completed his A.R.C.T.

The woman named Angela raised the lamp to eye level as if to inspect my face. Huh, was all she said before turning and motioning us to follow her into the darkness.

What passed for a mausoleum was in fact the entrance to a staircase that descended to a cavernous space far beneath Mount Pleasant Cemetery, removed from the city’s thrum where the screams of pain and shouts of triumph would go unheard. Displayed on the walls were the signed portraits of the PFC’s most distinguished luminaries: Nadia Boulanger and Sergei Rachmaninov, Wilhelm Kempff and Emanuel Ax, Martha Argerich, Louis Lortie, Charles Rosen, Oscar Peterson, Daniel Barenboim, Thelonius Monk, Tzimon Barto, Ivo Pogorelich. Sergei pointed to Nadia Boulanger’s portrait and said something but I couldn’t hear him because they were blasting a recording of Rudolph Serkin performing the final movement of Beethoven’s Emperor Piano Concerto. The music was getting people riled, which was the point, I suppose. Beethoven does that to people. Sergei leaned in close and shouted that Boulanger had been responsible for training many of the early members, teaching them hands-free tactics she had learned from her street-fighting days during the Nazi occupation. Flying kicks, knees to the groin, elbows to the kidney. She had also schooled people in the importance of vocalizing as you land the blow: a scream thrown up from the pelvic floor, thrust up and out with the diaphragm, could double the force of a solid head butt. And for those who couldn’t give up the punch, there were adaptations of Kung fu that permitted the delivery of a blow with an open hand. There was nothing so eye-watering as a palm strike to the nose.

In the centre of the room stood a metal cage around a raised wooden floor. Two guys my age were going at one another in the cage and, judging by the gashes and the sweat and the listless way they circled one another, they’d already been fighting for several rounds. The pair fell together, clutching each other’s heads, and the referee had to break them apart and send them to opposite corners. When the referee retreated from the centre of the ring, one of the pianists exploded from his corner, swinging his legs into a drop kick that connected with the other pianist’s jaw. And that was that. The pair fell to the floor, but one of them didn’t get up. The referee counted ten then declared the drop kick kid the winner. There were cheers and some half-hearted applause but, as Sergei explained, people were saving their enthusiasm for the evening’s higher profile match-ups. Sometime around midnight, Diana Krall would be squaring off with Chantal Kreviazuk, and while some of the purists felt that jazz pianists should have their own organization, most members didn’t discriminate on the basis of genre; people should be entitled to beat one another senseless regardless of piano style preferences. The headliners would fight in the early hours of the morning. Hélène Grimaud was making a play to unseat the reigning champion, Lang Lang, who only the week before had demolished Elton John and was despairing that he would ever find a viable contender.

The drop kick kid descended from the ring, sweat oozing through his silk robe, towel draped around his neck, cropped hair sticking up in a thousand different directions. His left eye was swollen shut and the cheekbone underneath had turned a deep purple. He paused in front of me and, glaring through his right eye, called me by name. It was only then that I recognized him, an acquaintance from the Conservatory who was a year ahead of me in his studies. When he got his A.R.C.T. he was soft, like a child’s teddy bear; a year later and look at him: ripped abs, bulging biceps, and forearms that would put Popeye to shame. You’d hardly know it was the same pianist.

So you’re gonna join the PFC. The drop kick kid spoke without a raised inflection at the end of his sentence; not a question, but the declaration of a fait accompli.

Thinking about it, I said.

The people standing within earshot gave me a look I couldn’t parse, as if I had offended them.

Angela climbed onto a stool and shouted to the room: Who can tell me the third rule of the Piano Fight Club?

In a chorus, the room shouted back: First-timers have to fight!

Sergei laid a hand on my shoulder: This is it, kid. This is where you decide whether or not you’re serious about being pianist.

It felt to me like that moment I experienced every summer in Muskoka, standing on the dock, poised to jump into the lake, afraid of the cold splash that waited for me. There was an instant when time stopped—after my feet had left the dock but before my body had struck the water—when I hovered mid-air and knew with certainty that I was about to greet the cold. I felt something similar whenever I stepped onto a concert stage and sat on a piano bench: a thousand pairs of eyes bearing down on me, the untold weight of their expectations fixing me to my seat, the horrible silence that sat in wait of my first notes. Once I struck the keys, there was no turning back; I had no choice but to perform to the final note and into the silence beyond.

I’m not dressed for it. But my excuse felt feeble even before it had left my lips.

Sergei’s only response was a wry twist to one corner of his mouth.

Fine, I said. And I pulled off my shirt and I handed it to Sergei.

Angela called to the crowd for a challenger to take up the honour of initiating a newcomer. I took no comfort from her next call to the crowd: Who wants to give this soft little boy a proper thrashing?

The kid pulled off his jacket and, with an exaggerated flourish, hurled it into the crowd. Underneath, he had two octaves of black and white keys tattooed across his chest and the words: “Scales are for pussies!” As if that weren’t enough, he had “Fuck Hanon” in block letters between his shoulder blades.

As I climbed into the cage, a recent grad from Juilliard raised a fist in the air and announced that he’d happily rearrange my teeth. At least I assumed he was a recent grad from Juilliard because he wore a leather jacket with the school crest on the left breast and “Class of ‘19” lettering on the opposite shoulder. Why would anybody lie about such a thing? The kid pulled off his jacket and, with an exaggerated flourish, hurled it into the crowd. Underneath, he had two octaves of black and white keys tattooed across his chest and the words: “Scales are for pussies!” As if that weren’t enough, he had “Fuck Hanon” in block letters between his shoulder blades.

The kid stood half a head taller than me and had at least 10 kilos on me. I couldn’t see how I was going to beat him. Perhaps sensing my self-doubt, Sergei waved me to the corner and, in a low voice, said: Remember the secret knock? The opening notes of Bach’s Aria? Don’t forget that rhythm. It’ll help you.

Yeah. Sure. Whatever.

My heart was pounding. Earlier in the year, Sergei had devoted an entire lesson to the heart beat. He was of the opinion that, while pre-concert jitters could be a useful (by keeping a performer keen-edged and in the moment), they could be problematic if the result was an elevated heart rate. Nothing fucks with our sense of timing quite like a trip hammer pounding in the chest. Sergei sometimes had a crude way of putting things, but he had a valid point. Our heart beat serves as a natural metronome. If we are accustomed to take our pace from our heart beat, we’ll start a piece too fast in performance situations because we’re nervous and our heart is beating faster than usual. He introduced a series of deep breathing exercises and bio-feedback routines to help me control my heart rate before concerts and exams. Presumably, a fight was just another performance situation so the same exercises should help me here. I drew in a deep breath and held for a count of five before expelling my breath for another count of five. I visualized a tropical beach with palm trees and gentle waves lapping at my toes. I imagined a pendulum swinging back and forth, bearing in its sweep a deeper rhythm: the heart beat of the whole planet.

When my heart beat had settled, I opened my eyes. The Juilliard grad leered at me, curling back his lips to reveal a missing tooth. This was meant to intimidate me but I didn’t take it that way, laughing instead, and provoking him to a simmering rage. This is how I would beat him. I would keep my calm and use my head while goading Big Julie to react with emotional outbursts. His rage would make him careless. He danced in his corner, bending his head to left and right, vocalizing hoo-hah, hoo-hah in an attempt to throw me off before the fight had even begun.

The referee stepped to the centre of the cage and summoned us to join him. You boys know the first rule of Piano Fight Club?

Don’t hurt fingers, we said in unison.

Good. Keep it clean. No closed fists. No stomping on fingers. No biting.

Right.

We fist bumped, then returned to our corners and waited for the bell.

I don’t remember much of my first match at the Piano Fight Club. Only that paradoxical mix of fear and joy that has become so familiar to me both in the ring and on the concert stage. Whether I’m taking an elbow to the solar plexus or running my fingers from one end of the keyboard to the other, I feel myself skirting along the edge of oblivion. A darkness descends over my eyes and I thrust through to a fuller sense of being. Every fight, every performance, every instant I place myself at risk, I feel like I’m being born all over again.

There is one moment from that first fight that I remember with clarity. I was on the mat and the Juilliard grad had kicked me in the chest. Because I was struggling to breathe, the referee sent him back to his corner and knelt beside me to see if he should call the fight. Everybody—myself included—thought I was finished. I hoisted myself to a sitting position and hawked blood onto the mat. But in that moment, with the jeers and the clackers, with the ref’s cigarette breath in my face, with the music blaring through the loudspeakers, a new score appeared to me in my mind’s ear. I’ve always hesitated to use the word spiritual to describe my experiences, and yet I can think of no better word to account for what happened to me in that moment. An energy drew me to my feet. I was not a solitary figure standing in the ring; I was the latest in an unbroken line that whispered through the ages with the mounting force of a hurricane or an atom bomb, the chanting ascetic in his cell, the Leipzig organ shaking the ground, the devil himself spinning out his twenty-four variations to a spellbound crowd, the tympani sounding the knock of doom, the twelve tones shattering like crystal in a maelstrom, and their ragged reinvention on the modern concert stage. All of this passed through my body like a shock of electricity and it levelled my opponent. I tapped out the opening notes of Bach’s Aria—one short rap, a pause as if to breathe, a second short rap followed by another pause, then three more short raps in quick succession—and sent my opponent flying to his corner. He lay bandy limbed on the mat and I climbed out of the ring with a fresh resolve.

When I got home, my parents were waiting for me in the dark. To my relief, they didn’t turn on the lights so they didn’t notice the bruises on my face and traces of blood on my clothes. When I explained that Sergei had taken me out with some of his friends to celebrate my A.R.C.T., their primary concern was that he might have procured liquor for an underage youth. I assured them that I hadn’t drunk anything harder than water; it was just a bunch of musical nerds getting together to enjoy the company of like-minded people.

It wasn’t until breakfast that my mother noticed. I approached the fridge with the grace of an elderly arthritic, and when I turned around with the milk carton, my mother saw the black eye and split lip. I smiled as much as the crusted scabs would allow; the twitch smarted and brought tears to my eyes. Mindful of the second rule of Piano Fight Club, I invented a story about tripping over a cyclist who had run a stop sign. I’m not a convincing liar, but denial can be a useful ally: my mother would have found it impossible to believe that her son willingly passed an evening thrashing pianists in a cemetery. But had she given any thought to the history of music, she would have acknowledged that the Piano Fight Club is not such a strange thing. Thanks to syphilis or depression or the fact that he injured a finger on a crackpot’s device designed to improve manual dexterity, Robert Schumann spent years in an insane asylum while Johannes Brahms bonked his wife. Then there are the secret photos of Aaron Copeland bare-assed in chaps which prove that his Rodeo had less to do with cowboys than with his sexual proclivities. And let’s not forget Frédéric Chopin whose bicycle club was more than simply a metaphor; even today, impassioned would-be necrophiliacs leave flowers at his grave.