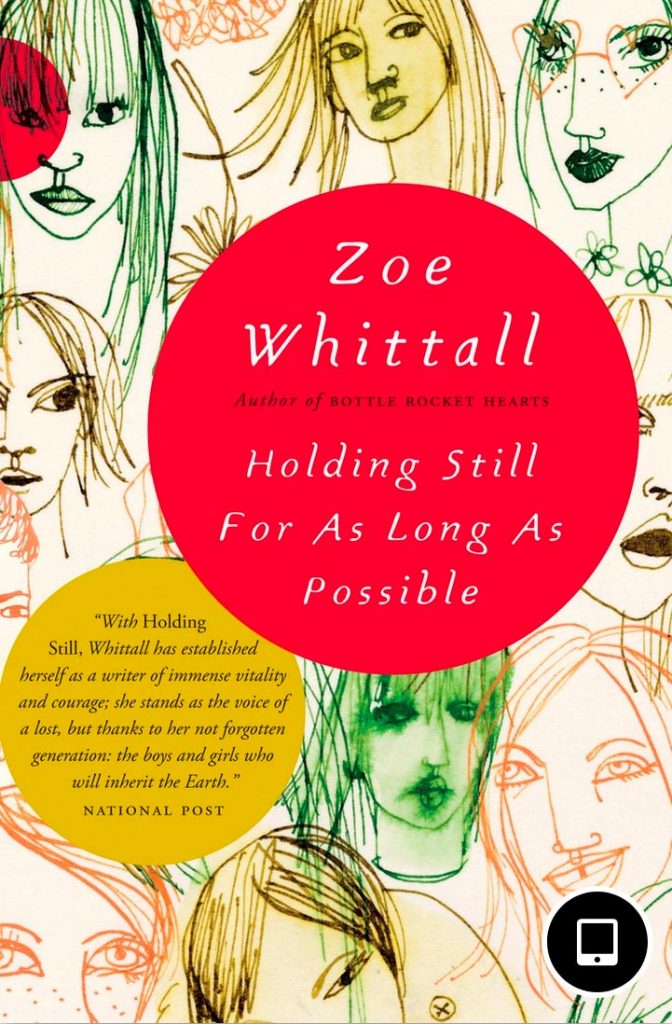

Zoe Whittall’s Holding Still For As Long As Possible is a novel about queer youth in Toronto. I’m not a queer youth in Toronto. I’m a straight middle-aged guy in Toronto. (I leave for another time the debate about whether straight people can identify as queer.) So I don’t feel acutely qualified to pronounce upon the accuracy or authenticity of Zoe Whittall’s portrayals. I’ll confine myself to the matter of place.

I’m fascinated by the role of place in fiction. What does it mean to give one’s settings an almost google-streetviewish specificity? With a comic self-consciousness, the previous generation of Canadian writers shied away from place. Why admit that you set your novel in a Toronto neighbourhood if that might limit your chances of breaking into the American market? Today, Canadian writers have shed their self-consciousness. It is an odd irony of the internet age and its global reach that Canadian writers no longer worry about placing their stories firmly on local ground. That may be a good thing. That may be an act of resistance.

I think it is a sound instinct that prompts today’s writers to give greater attention to the specificity of place. Although true of other elements in a novel, place in particular functions like a container which the reader is free to fill with meanings. While place can have meanings internal to the novel – e.g. Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl in Under the Volcano or the Mississippi River in Huckleberry Finn – these don’t preclude the intrusion of meanings from outside.

In Whittall’s novel, an important place is the intersection of Bathurst and Dundas in Toronto. On the northeast corner is the Toronto East General Hospital. Josh, a trans (FTM) paramedic, makes calls in the neighbourhoods around the hospital and often ends up delivering patients to the ER. One might say that his is a life of the body. Personally, he has coped with the fact that he was born with a body that didn’t mesh with the person inside. Professionally, he copes with the broken bodies of strangers – bodies in distress, bodies that have failed altogether.

Because this setting corresponds to a place in the world beyond the novel, it has the potential to engage readers in a way that is impossible in books like Conrad’s Nostromo (set in the imaginary country of Costaguana). I know the Toronto East General Hospital. I can’t possibly know Costaguana. I’ve accompanied my wife there for minor surgeries. Like Josh, I’ve eaten its questionable food and drunk its questionable coffee. I’ve filled prescriptions at its drug store. And at the end of the day, I’ve paid the most expensive parking charges I’ve ever paid in my life. Inevitably, references to places I know cause me to import meanings into my reading which are personal and idiosyncratic. I read about Josh running across the road to the Tim’s for a coffee and I remember how I fumbled for change to hire a wheelchair at the hospital entrance with the Tim’s in view.

Then there’s Josh’s girlfriend, Amy, whose parents live in a “North York mansion”. This probably refers to the Post Road/Bridle Path neighbourhood, and while that lifestyle isn’t exactly within my personal experience, I have managed to cadge an invite to a party there and am never above using the Bridle Path as a shortcut. The allusion to Amy’s place of origin – her pedigree, if you like – tells me that she can never really fit in with the crowd that hangs out at the Gladstone Hotel, and it also explains Josh’s awkwardness whenever he has dinner with her parents. It lends their breakup a sense of inevitability.

The third narrative voice belongs to Billy aka Hilary Stevenson, a minor pop sensation at 16, now washed up at 25, was with Maria for seven years, broke up, moved in with Roxy, but has a thing for Josh. In Whittall’s world, the dirty secret that may keep the new relationship from launching is not the fact that Josh is trans (Billy’s sexuality is too fluid for this to matter) but the fact that Billy suffers from an anxiety disorder. She is afraid Josh will find out about her panic attacks and the spells that make her feel like she’s flying apart. In Whittall’s world, the body determines nothing; identity is more than the body.

A place is like a body. A place determines nothing. My identity is more than my place. Everyone invests the place they live with stories. The remarkable thing about place is that it can serve as a point of intersection for a diversity of stories. I have a place on the same streets where Whittall and her characters find their place. And while our stories are, in some ways, widely divergent, the discomforts of difference vanish when we discover, quite literally, our common ground.

As I said at the outset, I’m about as far as one can get from queer youth in Toronto. But the specificity Whittall gives to place in her novel, and the fact that it intersects with my own environment, helps me to project myself imaginatively into her story and to encounter her characters with empathy. As writers demonstrate again and again, a sense of place is not essential to a good story. Nevertheless, when the characters are sufficiently queer (to a conventional soul like me), placing them in a world I inhabit forces me to see them as real in a way I could never see, say, if they lived and played and fucked in Hogwarts.