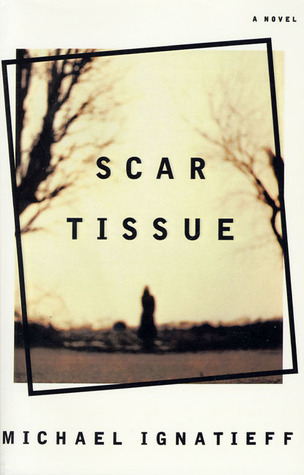

With Canada’s federal liberal party leadership race coming to a close today, and a copy of the Booker–nominated novel, Scar Tissue, sitting unread on my book shelf, I decided to sit down yesterday and see for myself what I could learn about Michael Ignatieff. He is, after all, the front runner and, as such, has a good chance of one day leading both the liberal party and this country. Is he the sort of man I could trust in the Prime Minister’s Office? Reading a novel isn’t exactly a “scientific” method of discerning a man’s leadership skills. It contains no policy statements, no concern for economics or foreign affairs. Nevertheless, I have come away with definite (favourable) impressions and have concluded that whatever Ignatieff might lack in direct political experience he makes up for in deep intelligence, clear–sighted thinking, and a compassionate view of human relations.

The novel touches on themes of wholeness, the burden of conscious selfhood, the role of the written word, family relationships, loss and grieving, and (not surprising given that he is a philosopher) the ancient problem of all western problems – the relationship of spirit and body. When I read fiction, I always proceed on the premise that the writing is intrinsically a spiritual act, like prayer or communion, and, therefore, that the author must be a spiritual person. Indeed, Scar Tissue, is an intensely spiritual meditation that tracks a man’s transition into full adulthood with the death of his parents. Such spiritual musings seem incompatible with the author’s political aspirations, and yet, perhaps this sense of incompatibility merely reflects the extent to which my own thinking is dominated by the popular bias which says that spirituality and politics belong in separate spheres. George W. Bush is a strong argument for such a separation. And yet I think we all yearn for the possibility that our political leaders might be guided by a sane and grounded set of values. Ignatieff’s writing suggests that this possibility might be more fully realized at least within the sphere of Canadian political life.

In terms of plot, Scar Tissue is a simple novel. A mother’s occasional lapses become more pronounced and lead to a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Two sons, one living nearby, one more distant, try to support their father, but when the old man dies unexpectedly, they find themselves forced to institutionalize their mother and sell the family home. The narrator, the younger son who becomes the primary caregiver, also experiences difficulties coming to terms with his changing role and place in life. This manifests itself in the usual maladaptive behaviour of midlife – marriage breakdown, vocational crisis, a general grappling with the fear that life might be meaningless. The narrator’s behaviour calls to mind a quote by the Marquise de Merteuil in Dangerous Liaisons: “Like most intellectuals, he is intensely stupid.” For example, he is invited to give a speech to the local Rotarians, and his parents have come to hear him. He speaks in abstract terms about the nature of dying. When the speech is done, his wife asks how he could speak so obviously of his own mother’s demise while she is present. It hasn’t even occurred to him that his abstractions are really about something deeply personal. There is a succession of failures—missed opportunities for insight—which reveal a flawed, but very honest and very human, narrator.

But insight does happen. The brother introduces the narrator to Moe, a husband and father who has lived for five years with ALS and is now close to death. Moe can no longer speak, but blows through a tube to produce words on a computer screen. Even a few short sentences take twenty minutes to write. But more striking is the fact that every effort costs Moe a few more minutes of his life span. Moe is a kind of guru, a man intimately acquainted with the very kind of knowledge the narrator is seeking. The narrator has so many questions, and Moe gives his answers freely, losing precious time in the process, but begrudging none of it. One of the things Moe values most about his dying is the fact that he can be conscious of it even to the very end. This is in stark contrast to the mother who cannot even recognize herself much less think about anything. Here we find value in words. “[W]hen illness pares us back to our core we remain creatures of the word.” Moe does whatever he can – even shorten his own life – to continue expressing himself; but the mother devolves into an incoherent gurgling. Words are a way to confirm one’s self as a conscious being. And so the narrator’s words, whether as speeches to Rotarians or as lectures to his students (or as this novel) are not so much efforts to explain things to himself as to offer up a positive confirmation of his existence.

Words have their limits. There is a whatness that we can never tell. And so, near the end of the novel, the narrator notes: “What happens cannot be redeemed. It can never be anything other than what it is. We tell stories as if to refuse this truth, as if to say that we make our fate, rather than simply endure it. But in truth we make nothing.” Perhaps this is why Ignatieff has abandoned his stories for politics. Perhaps he believes that words might have more effect in shaping policy than in shaping hearts. I doubt this is true. Has Ignatieff not heard that writing is, essentially, a political act?

At the time of writing, the leadership race has resolved itself with Ignatieff in the lead, followed by Bob Rae & Stephan Dion. I hope he loses so he has time to write more novels.